The challenges facing emergency medicine (EM) services in Canada reflect the limitations of the entire healthcare system. The emergency department (ED) is situated in the healthcare system in such a way that failures of other parts of the healthcare system to support patients increases ED usage and affects ED efficiency. Thus gaps and shortcomings in the healthcare system often first appear in the ED1,2. This phenomenon is amplified in rural settings, which have additional site-specific barriers to the provision of quality EM care3-6.

Challenges facing rural physicians are well documented. Several Canadian studies show that access to diagnostic tools and specialist support in rural EDs is limited. Patient care is impacted by barriers to transport between rural communities and larger centers due to factors such as distance, geography, and weather3-6. This is a well-known barrier to the comfort and satisfaction of rural EM physicians7,8. These conditions create community-specific gaps and needs.

Physicians practicing rural EM in rural Canada are typically generalists working in single coverage departments. Back-up from local and regional colleagues is important, and expectations regarding support influence physicians' decisions to practice rurally9-11. Rural physicians are keenly aware that they must be proficient in multiple skills and procedures12,13. Studies from Canada and the USA show that, due to lack of access to the patient volume necessary to maintain proficiency, rural physicians experience anxiety around the deterioration of procedural skills over time, and identify these skills as a top learning need12-15. Other work from Canada and Australia shows that, while training increases skills and confidence in the short-term, maintaining skills over the long term is challenging for rural physicians8,13,14. Finally, qualitative work from Canada, Australia, and the USA has identified many factors associated with increased professional satisfaction and retention for rural and urban primary care physicians, including flexible and innovative work environments, having strong teams with interprofessional support, and access to educational opportunities16-20.

This study explores physicians' experiences of the barriers and enablers to EM care in rural British Columbia (BC) through a series of focus groups with rural physicians. The goal of the study was to generate a theoretical model describing the rural EM practice environment, and to understand the factors influencing rural physicians' strategies to survive and thrive in that environment21.

These findings emerged from a study undertaken to explore the needs of rural EM physicians in BC, and to inform evidence-based continuing medical education (CME) to support rural EM care. Nine focus groups were conducted, eight with 39 rural physicians, and one with five rural interprofessional team members (ie nurses, paramedics, respiratory therapists). There were also five interviews with seven key informants. This study reports findings from the focus groups with rural physicians. The parts of the study not described here have been described in previous work22. All elements of the data collection and analysis were informed by techniques from grounded theory21,23-25. The research questions centered on three areas: rural EM physician recruitment and retention, system and workplace factors that support or hinder their work, and CME related to EM.

The demographic emphasis of each physician focus group was intentionally selected to allow the broadest possible variety of physician perspectives on rural EM practice. For example, capturing experiences that span the full 'lifecycle' of a rural EM physician was made possible by speaking to physicians new to rural EM practice, those established in practice, and those no longer practicing rural EM. The general inclusion criteria for the study, and specific inclusion criteria of each physician focus group, are shown in Table 1.

Focus group recruitment and selection

Participants were recruited through an online survey distributed via email to all rural physicians in the University of British Columbia Division of Continuing Professional Development (UBC CPD) database. The recruitment survey collected demographic information, which was used to screen participants.

Participants were purposively screened for maximum variation on rural medical experience, age, geographical location, and sex to ensure the findings represented the experiences of a diverse group of rural physicians. To be eligible to participate in the study, physicians needed to live, or have lived, in a rural community in BC26.

Data collection

Semi-structured focus group protocols were developed to address the research questions and the specific inclusion criteria for each group, allowing us to leverage the diversity of the focus groups. Following the principles of grounded theory, probes were iteratively adjusted to reflect emerging findings.

The focus groups were 60-90 minutes in length, involved 4-6 participants each, and were conducted by teleconference to accommodate remote participation. A single rural physician with extensive and current experience in rural EM practice moderated all the focus groups. Other members of the research team were also present. All focus groups were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Analysis

Data were collected and analysed simultaneously, leading to an evolving list of codes that was revised as new themes and concepts emerged21,23-25,27. Transcripts were coded for themes using NVivo software v10 (QSR International; http://www.qsrinternational.com). In addition to working in pairs to code transcripts and reconcile differences, the study team met several times to refine emerging themes and codes, enabling the inclusion of multiple perspectives on the data and verification of the reliability of the findings28. Borrowing from the grounded theory model developed by Morrow and Smith, and using Strauss and Corbin's framework for grounded theory, a framework for the theoretical model was built to help understand how rural physicians survive and thrive in rural EM practice21,29. The data were then re-examined with a wide lens, and each conceptual unit of data was compartmentalized into the theoretical model.

Participants each completed a consent form prior to participation, and received an honorarium for their participation. The study was approved by UBC's Behavioural Research Ethics Board.

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the University of British Columbia Research Ethics Board (H14-00181).

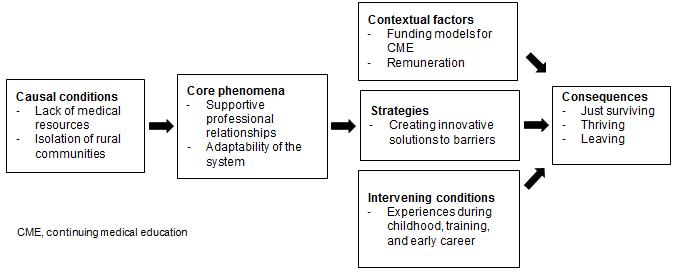

Overall, participants described enjoying their work in rural EM. However, they also reported a number of challenges. Figure 1 presents a theoretical model describing influential factors in the rural EM practice environment, and the complex interplay between these elements.

Figure 1: Theoretical model describing the rural emergency medicine (EM) practice environment and key factors that affect physicians' experience of rural EM practice

Causal conditions

The data reveal two causal conditions influencing the core phenomena in physicians' experiences of rural EM practice. Together, the causal conditions combine to generate physicians' common experience of feeling fearful, isolated, and under-supported in rural EM practice. The nature of the causal conditions means the challenges the conditions pose are community-specific.

Lack of medical resources: An inherent feature of rural medicine is a lack of access to medical and human resources (eg personnel, speciality skills, and diagnostic equipment), although the specific locally available resources can vary widely. Most physicians practicing EM in rural communities work as the sole physician in the ER, often with only one or two nursing colleagues on site. This lack of human and medical resources creates strong feelings of 'being alone'.

Isolation of rural communities: Rural communities in BC experience varying levels of isolation. While some communities are close to referral centers, others have barriers of topography and distance. In some communities, inclement weather can make ground or air emergency transportation unavailable.

Core phenomena

The causal conditions contribute to the intensity of the two core phenomena participants described.

Supportive professional relationships: The presence of supportive professional relationships within rural communities was described as integral to the satisfaction and sustainability of rural EM practice. Having a colleague to speak to can mitigate some of the fear rural EM physicians feel and can make sure they do not 'feel alone' in the ER. One physician said the fear of 'being alone when the rubber hits the road keeps me up at night'. Another said, 'We all struggle with always, always feeling like [we're] not quite up to what might walk in the door'. Strong relationships help rural EM physicians navigate the challenges created by a lack of local medical resources and the isolation of rural communities.

While the most significant professional relationships for rural physicians are those between the physician and the local healthcare team (ie nurses and other physician colleagues), relationships with colleagues at regional referral centers were also described as important. However, some groups of physicians (eg locums, international medical graduates (IMGs), and physicians new to practice) lack these relationships because they are not as embedded in the local community, and their inability to access the same levels of collegial support is a significant disadvantage.

It's amazing to me how supportive [my team is], and the camaraderie that exists up here. I couldn't ask for better coworkers. I've called one of them in at 11:00 at night, 1:00 in the morning for help or a second opinion, and no one bats an eye about helping each other. It's awesome.

I rely on my colleagues quite a bit. Part of the reason I came here is because the doctors are willing to help out. Whenever I've needed backup, I've always been able to get someone.

One of the challenges I've found [as a locum] in going to a new place is in terms of the support you have in that community. Pretty much as a rule you're in single coverage ERs, [so] I don't really have a clear sense of who is on-call or whom I can call if I need help. I don't have a personal relationship with GPs in that town, so if I get into trouble it's a little bit nerve wracking.

Failure of the system to adapt to community-specific needs: Rural communities have specific needs that arise from the unique combination of available local medical resources and community isolation. When the healthcare system does not recognize and respond to these unique needs, it creates barriers to the provision of healthcare.

Provincial emergency transportation system Problems with the provincial transport system were routinely cited by participants as being their number one challenge in the provision of rural EM care. One rural physician said, 'The main issue is transport. If someone could make the transport headaches go away, I would be very happy'. The provincial transport system is one aspect of the broader healthcare system that participants said frequently fails to respond to their needs. As rural ERs lack at least some essential services to manage critical conditions, such patients are routinely stabilised in the rural ER and then transferred to larger centers for further care. The BC Emergency Health Services (BCEHS) coordinates road and air medical transport services across BC.

Participants described how, once they decide a transfer is necessary, they feel the system must respond immediately, recognizing their lack of resources to manage a deteriorating patient. However, BCEHS often has priorities that can conflict with physicians' needs, leaving rural physicians feeling unsupported in their efforts to obtain the care they feel their patient needs. Participants shared numerous accounts describing BCEHS staff as unaccommodating, while at the same time lacking the necessary medical knowledge to make transport decisions.

Physicians often have to remain on the phone with BCEHS for long periods of time while trying to arrange transportation. One participant said, 'Arranging transport in a timely manner has been our biggest frustration'. Explaining how this poses challenges for solo physicians who are trying to care for unstable patients, another participant said, '[Transport is] a constant headache. It's not good patient care'. Once the transport has been initiated, an additional challenge reported is a lack of appropriate communication from BCEHS back to rural physicians. This further contributes to feelings of being unsupported.

The wait times and reliability [are] pretty terrible. They say there's going to be a plane there in two hours, then they say, 'There's no planes, it's going to be another four hours'. I had a [case last year] and it took me two hours on the phone, I talked to seven different physicians. That was an extreme experience, but it takes longer than it should.

I don't want to have to explain to someone without any medical background why I think this patient is potentially life and limb. They need to trust that I've made that decision based on my clinical background.

Continuing medical education CME is another aspect of the healthcare system where flexibility is important. Most rural physicians agree that traditional CME is often inaccessible or irrelevant. Courses offered in urban centers tend to focus on urban issues and do not reflect the realities of rural practice. Travelling to urban centers can be expensive and time consuming, and can leave local colleagues without back-up. Courses offered outside the community remove the opportunity for rural physicians to learn with their local healthcare team. Participants clearly expressed a need for more rurally specific, interprofessional, and community-based learning opportunities. Where such programs exist, they were universally seen as valuable.

What's missing when you take a course outside of your rural [community] is you go as a lone physician and then you come back to your hospital and you haven't been with your team and in your hospital. [To keep things] flowing smoothly in your department, CPD locally is critical.

It's frustrating going to these very urban-focused courses. There are times when I can't get a chest x-ray, where it's me or the nurse doing the blood work. So when [instructors say], 'Okay, you'll call in your anaesthesia and you'll have [respiratory therapists] setting up the ventilator ...' that's just not my reality. [Urban-focused courses make] assumptions that may seem like basic things, but aren't the reality of rural [EM].

Healthcare policies that fail to acknowledge rural realities Participants described frequently feeling frustrated by elements of the regional and provincial healthcare system they feel fail to recognize the reality of rural healthcare, resulting in community needs being ignored. They described examples of healthcare policies they believed create a further lack of resources to deal with problems that will predictably arise (such as an inability to transfer a patient due to inclement weather), rather than addressing existing barriers to EM care.

We don't have any blood ... [If someone needs blood] they have to drive four hours one way. It [would] be nice to have O-negative blood if we have some disaster ... Transport can take a day or two because the weather can be bad ... That's been one of our problems here, and they won't listen to us. Nobody understands.

We are not allowed to hold [psychiatry] patients at our hospital. It's not deemed safe and we don't have the staffing or appropriate rooms. It creates a big problem. Often we end up having to hold them here [because no other options exist for emergency care] which makes the nursing staff uncomfortable, and rightfully so.

Context

Rural physicians develop strategies to negotiate barriers to care based on their experience of the core phenomena. These strategies are influenced by two contextual factors.

Funding models for CME: There are numerous sources of funding for CME for rural healthcare providers, and they are helpful. These funds help offset the significant costs of accessing CME faced by rural practitioners. However, some rural physicians cannot access these funds. Physicians who are new to rural practice (eg new graduates, IMGs, or people coming from other parts of BC or Canada) are unable to access rural CME funding for the first few years. Physicians practicing in very small communities lack access to the funds that are available to physicians in larger communities. Finally, most CME funds do not support interprofessional team learning, making this valued form of education inaccessible to most rural healthcare providers.

When [you're new to rural practice and] ... you're at the steepest part of your learning curve, there's not a lot of funding to support that. After [you're here] a few years the money starts flowing in, which seems a little back-to-front.

Remuneration systems: While numerous participants reported being satisfied with their income and levels of compensation, they noted that particular systems of remuneration support EM care better than others. Some funding programs allow the medical community considerable discretion in how to direct the funds, and this was described as being helpful and supportive of sustainable rural EM services. The flexibility of these remuneration models enables communities to use these funds to support specific local needs.

The ... full-time docs take a ... smaller cut of [the on-call funds] in order to subsidize the GP's who have offices, which is very generous of them.

We use [funding programs to] pay for the less lucrative shifts or the night shifts, the ones that the people don't want, and I think it's great. I think we get paid really well.

Intervening conditions

Experiences during childhood, training, and early career: Physicians' experiences before beginning rural practice influence their experience of rural practice. Physicians who grew up in rural areas or were attracted to the outdoors are predisposed to enjoy rural practice. Positive rural experiences during clerkship and residency are important in guiding their decisions to practice rurally. Physicians from urban training programs universally reported inadequate training in EM, and felt unprepared for rural EM practice, while those in rural residency programs did not. IMGs experience difficulties as a result of differences in training and expectations from the countries in which they trained and that of rural BC.

[My residency training] was perfect. It was a rural program so [we] already knew that we were going to be working emerg[ency]. We tried to put as much energy and effort on emerg as we could. I felt ready to work in a rural emerg.

My experience in emergency is quite limited. During my first year [in an urban] residency [program] I had only one month for emergency, and I can't say that was a real [ER] because you have support from all the specialists. I found [the shift to a rural community] with no specialist support quite challenging.

I didn't feel adequately prepared for the job I was doing. Emerg in the UK is very different to emerg here and I felt very much thrown in the deep end.

Strategies

In response to the challenges of rural EM practice, study participants identified numerous strategies that flow from the core phenomena. They draw on the strength of professional relationships and create ways for systems of support to meet local needs.

Bypassing the transport system: Participants address the challenge of inadequate access to emergency transportation creatively. Some leverage the power of their professional relationships with colleagues in regional centers to improve patient care, or expedite patient transport. To arrange timely consults for patients, participants described how they call colleagues with whom they have good relationships, or avoid calling colleagues with whom they have negative relationships. Several communities have established 'no refusal' policies with regional centers, which speed up transfers of seriously ill patients. Others strategies help overcome a lack of system responsiveness to community-specific needs. After finding existing support to be inadequate, physicians in at least one community created their own inter-facility transport team. In response to transport staff insisting on speaking only with physicians to initiate emergency transfers - even as the physician is actively managing a medical emergency - one healthcare team now wears headsets to stay on the phone while caring for patients.

If I've got a good sense of where [the patient is] going ... and I know there's likely to be a bed, I'll pre-call the [specialist] and then, having done a lot of the initial work for them, I'll call [the transport team]. Then they're just arranging transport.

There are certain specialists [whose] opinions I don't trust. If ... I don't need an urgent opinion, I'll call and ask who's on call and then decide if I want to talk to them. If someone's really sick I'll always call and talk to whomever is available, but sometimes I wait an extra day to talk to someone I trust more.

We're going to form our own transport team because we're three hours from [the nearest referral center] and in the middle of an avalanche we're three hours from nowhere. We're looking at certifying nurses so they can go with patients, having trauma carts [ready] to be thrown into the ambulance ... Because we haven't got time to wait for an ambulance to come.

'Home-grown' CME: Participants described the importance of accessing training to mitigate the fear and anxiety they experience. To address the gaps created by traditional models of CME, rural physicians in many communities have created local interprofessional CME opportunities such as simulation-based learning sessions, equipment and skills training, and team building activities. Elements of the core phenomena, such as failure of the system to recognise the realities of rural practice, and contextual factors such as funding models, provide the impetus and opportunity to create these strategies.

We're now running monthly simulations. We involve our residents and the nurses come, and we have pizza and beer. It's been good for camaraderie ... for our skill level, for the nurses and physicians working together, and for improving communication. We've done a lot with education, which I think has been the big key to making our department run better. It's been all disciplines and that has helped.

Creative scheduling and back-up: In communities where formal systems for back-up in the ER are lacking, participants have created informal support systems. Scheduling ER shifts around clinic hours and other commitments is another challenge for rural generalist physicians, so some communities have rearranged ER shifts to reduce the burden on individual physicians. This strategy is supported by core phenomena such as supportive professional relationships within the community and contextual factors such as flexible remuneration systems that work to support these solutions. One physician described the approach in his community, saying, 'There's no second on-call, it's just informal ... People will tell you, 'I'm around if you need anything'. It is really supportive'.

Consequences

Our participants described three consequences – just surviving, thriving, and leaving. It is proposed that the challenges of rural EM practice require rural physicians to develop a sense of mastery in their practice, or quit. It is theorized that rural physicians transition through a liminal stage of just surviving before arriving at one of the two end points.

Just surviving: Many physicians enter rural EM practice for the first time feeling overwhelmed. In this phase, physicians are struggling under, or merely tolerating, the conditions of rural EM practice. At this point, they have neither developed mastery in their practice nor have they come to enjoy it.

Initially I found it pretty terrifying. Over time as you get to know the other staff in the hospital and feel more comfortable and know where you can refer people to, and what the expectations are, it's become far easier. Now I enjoy my emergency work.

Thriving: The majority of rural physicians are able to adapt to the challenges of rural EM practice in ways that allow them to thrive. They access further training to get more comfortable, they develop supportive professional relationships, they get more experience, and eventually they find they enjoy rural EM. They flourish in the challenges, pace, and camaraderie of the work, and they enjoy the broad scope of practice. For these physicians, rural EM practice becomes exciting and rewarding.

I really enjoy emerg. I could never work in urban medicine because I would miss out on the hospital based care. That's extremely important, to feel that I'm employing the full skill set that I have.

I can't really put a finger on what ... turned me on to [rural EM practice] except just doing it more and more and realizing that it was a good fit for me. I liked being hands-on, I liked doing 10 things at once. I liked the variety and the pace of it.

Leaving: Some physicians choose to leave EM practice. Some of the reasons reported for leaving EM are lack of support from local colleagues, and not enjoying the work. Other physicians experienced changes in their practice environment, such as increased physician supply, hospital closures, and demographic changes in the community, leading them to feel they could opt out of EM practice. Other physicians felt they could not keep up with the pace of the ER as they got older.

Normally, there was nobody else on call. I had nursing colleagues but it was just me on call for the ER ... There didn't seem to be any extra support. I found that tough. [Also,] I had conflict [with] the people I worked with ... so we decided to leave ... I was happy when I left. It was a bit of a relief, [a] weight off my shoulders ...

[The ER] took away time from patients that I enjoyed seeing in the office ... There wasn't that longitudinal relationship ... so I don't miss that at all.

I mean there's no doubt about it as, as you age, and I'm 63 now, your energy level to stand on your feet for 12 hours ... does decline a bit and your sense of excitement for taking that on.

Discussion

This study is the first, to the authors' knowledge, to provide a theoretical framework for understanding the complex environment in which rural EM physicians practice, and key factors that influence their job satisfaction. Lack of medical and human resources and community isolation create fear and anxiety for rural EM practitioners. These feelings are mitigated by supportive professional relationships, and are amplified by aspects of the healthcare system that cannot adapt to local medical needs. Experiences during childhood, training, and early on in rural physicians' careers and models of funding for CME and remuneration systems contribute to a range of coping strategies. These strategies leverage supportive professional relationships to deal with challenges in the provision of EM care, and create innovative solutions that improve existing supports. When successful, these strategies enable rural physicians to transition through the initial phase of just surviving in rural EM practice, into thriving. In some cases, for a variety of reasons, rural physicians choose not to remain in rural practice.

The causal conditions identified are consistent with existing work showing that, despite enjoying their work, many rural physicians experience feelings of fear and isolation in rural practice12,13. Existing research has also described the variation in rural practice environments and the numerous challenges physicians practicing in these environments face3-5. The literature also supports the finding that, as an intervening condition, experiences during childhood, training, and early career can influence physicians' decisions to practice in rural areas10,30,31. The existing literature confirms the authors' finding that collegiality between, and support from, physicians and allied healthcare professionals, both within and outside the local team, increased physician satisfaction16,17,19,20. No previous literature has identified the significance of challenges arising from dealing with inflexibility of a healthcare system that is unable to adapt to meet specific local needs been previously identified. Recognizing how professional relationships and inflexibility in the system influence the strategies rural physicians develop to meet challenges in the provision of EM care could significantly inform changes to increase support for rural EM care.

Limitations

Since participants were located across rural BC, focus groups were held via teleconference, which may have impacted the discussion by eliminating non-verbal cues and hindering the natural flow of conversation. Attempts to mitigate these challenges were made by creating a virtual seating chart for participants, which included the names and communities of all the participants on the call. Recruitment bias may have arisen in the study because the self-selected participants may be more engaged in efforts to improve the system than those who did not respond. Due to budget constraints, the number of focus groups and key informant interviews conducted was restricted at the outset of the study. However, the wide range of participant experiences included in the study, and the rigour of the methodological approach, offset this limitation.

What study participants – rural BC physicians – reported was translated into a model describing their experiences. As such, the theory excludes other perspectives in the BC rural healthcare system. However, the strength of the theory is in its in-depth exploration of the experiences of this vital element of the healthcare system.

Participants commented specifically on the BC healthcare system, so aspects of the findings may not be generalizable to contexts outside rural BC. However, the causal conditions of a lack of medical resources and isolation of rural communities, and the intervening conditions of physicians' experiences during childhood and training, have been previously identified as issues affecting rural physicians3-6,9-11. While the literature has not yet demonstrated the importance of supportive professional relationships and system responsiveness (the core phenomena), these issues arose frequently in the focus groups. As such, it is hypothesized that these elements of this theoretical model have applicability to other rural contexts across Canada and in other countries.

This study provides a theoretical model that described the complex practice environment of rural physicians practicing EM, and the coping strategies they employ to navigate challenges they face. This model gives a voice to the rural canary in the coalmine. Use of this model could help policy makers incorporate the experiences of rural EM providers in creating or improving healthcare system supports and, ultimately, patient care. Future research is needed to affirm the hypotheses and test their generalizability.

Acknowledgements

The Rural Emergency Medicine Needs Assessment study was conducted by the University of British Columbia's (UBC) Rural Continuing Professional Development Program. Funding for the study was administered by the Rural Coordination Centre of British Columbia on behalf of the Joint Standing Committee on Rural Issues, which includes representation from the provincial government of BC and the Doctors of BC.

The authors were impressed by the dedication of the participants in this study to their patients and communities and thank them for participating.

The authors would like to acknowledge Dr Ray Markham, Ms Gurveen Grewal, Ms Alexandra Hatry, and other UBC Division of Continuing Professional Development staff for their contributions to this study. They are grateful to the external reviewers, Dr Jude Kornelson and Dr Bob Woollard.

This study was supported by the Joint Standing Committee on Rural Issues, a joint collaborative committee of the BC Ministry of Health and the Doctors of BC, and administered by the Rural Coordination Centre of BC.

References