Introduction

This article explores health and wellbeing related findings of a major 3-year study of arts activity in the very remote Barkly Region of the Northern Territory (NT), Australia1. The study sought to examine the contribution that the arts and creativity make to holistic regional development in this desert region. Notably, arts–health effects were reported from multiple arts-centred and other activities, programs, and organisations within the region. Activities refers to single or infrequent arts activities facilitated by arts centres and other organisations. Programs refers to more sustained offerings of commercial or non-commercial arts activities such as daily, weekly or monthly painting, music recording or radio broadcasting opportunities. Organisations refers to arts and non-arts organisations involved in the wider Barkly arts–health ecology, which we discuss further below. Our article offers a snapshot of the overall arts–health ecology in the Barkly in order to advance our understanding of how the arts can be inextricably intertwined with social, cultural, political and place-based health determinants in remote contexts1. These insights are illuminating for health policies, and practices in remote regions more broadly.

The Barkly is a highly creative region with seven art centres and a range of creative practices occurring across its multicultural population. Many of the art centres and organisations have been in operation for a number of decades, including Barkly Regional Arts (established 1996), The Pink Palace (established in the 1990s; now closed), Nyinkka Nyunyu (established 2003), Ampilatwatja arts community (established in 1999; and the art centre, 2007–2008), and Arlpwe Art and Culture Centre (established 2008)1. Our research showed that many artists practised in the region; maintained their connections to Country, social and kin networks; and, in a number of cases, earned an income1. Alongside the Barkly’s cultural and artistic strengths, there exists extreme socioeconomic disadvantage, with indicators of homelessness, domestic violence, unemployment, poverty and ill health at much higher than national averages. Extreme weather conditions are experienced for long consecutive periods, and distances between communities are many hundreds of kilometres, with the roads in very poor condition1.

Discussions of health and wellbeing in this article are prefaced with First Nations’ conceptions of health due to our own positionality as researchers (NS and SO are Wiradjuri), and the significant proportion of the Barkly Region’s population and study participants who are First Nations Peoples. Authors of international arts–health literature typically define health according to the WHO2 longstanding definition of health as a ‘state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity’2 (p. 1). In that context, ‘[w]ellbeing refers to a positive rather than neutral state, framing health as a positive aspiration’ that has both individual and societal causes and effects3. Outside of those definitions, the National Strategic Framework for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples’ Mental Health and Social and Emotional Wellbeing 2017–20234 emphasised the holistic, harmonious and interconnected nature of health and wellbeing, explaining that the Aboriginal concept of health is holistic, encompassing mental health and physical, cultural and spiritual health. This holistic concept does not just refer to the whole body but is in fact steeped in harmonised interrelations that constitute cultural wellbeing. These interrelating factors can be categorised largely into spiritual, environmental, ideological, political, social, economic, mental and physical factors. It is crucial to understand that, when the harmony of these interrelations is disrupted, Aboriginal ill health will persist.

As such, we frame health and wellbeing as encompassing holistic individual and collective experiences and states of being that have cultural, intergenerational, social, environmental, economic and political determinants and effects.

The authors come to this work as diverse First Nations and non-Indigenous academics living in Australia. NS and SO are Wiradjuri academics, and SW and KA are non-Indigenous academics of Anglo-European heritage; B-LB is a migrant from South Africa. RG is a research partner representative and long term non-Indigenous resident in the NT with links to the Barkly Region through her role with research partner Regional Development Australia NT. We represent diverse cultural backgrounds, genders, expertise, and all share a background in creative practice. NS and B-LB had prior relationships with the Barkly Region and research partners through previous arts-based service learning activities and collaborations.

Background

Existing literature documents different ways that the arts contribute to regional and remote health and wellbeing through direct individual, environmental and social health determinant effects4-6. Artmaking and engagement are known to have intrinsic and individual health and wellbeing effects for mental health and mindfulness, emotional regulation, enjoyment, and relief of physical and emotional pain and (dis)stress alongside promoting spiritual connection to self, others and environment7. Arts and creative practice are also central to healing in culturally informed and trauma-integrated approaches to health and human services8.

There is increasing evidence from health researchers and professionals on how arts practices develop and maintain cultural connection and positive health and wellbeing outcomes for First Nations Peoples internationally9. Arts centres and organisations within Australia are expanding their role in health promotion programs and partnerships. The term arts centre refers to local arts organisations often run by members of the local community and managed by a board operating as not-for-profit entity. Arts centres often represent artists in the production and sale of works for artist members10. While many arts centres focus on developing First Nations artmaking and sales, our study included centres that were both First Nations focused and serving the general community. The increasing role of arts centres in health and wellbeing promotion is in line with international policy and arts–health research supporting the role of arts in health outcomes. In Australia, Lindeman, et al explored the impact of art programs for people living with dementia and their carers, finding a mutual benefit to both groups especially when delivered in environments that are ‘culturally revered’11 (p. 128). Others have explored the role of arts centres in supporting Elders as part of culturally coherent and informed intergenerational models of community care12.

Arts–health partnerships are being used to enhance the effectiveness of clinical health service provision in very rural and remote areas. For instance, Sinclair et al’s evaluation of The Western Desert Kidney Health Project, a community arts program that visited 10 predominantly First Nations very remote communities in Western Australia, found that the program significantly enhanced clinical screening activities for kidney disease13. Rentschler et al’s study of the impact of the arts on social inclusion in regional Australia found that social inclusion was tied to determinants of health and wellbeing – both individual and collective – such as employment, income, discrimination, crime, housing, and family and community coherence14 (p. 5). This work is notable for its structural approach to social inclusion as an ‘active process by which the personal and structural impacts of socio-economic disadvantage are addressed’14 (p. 5).

The arts are often associated with connections to culture and community as reflected in research over at least the past three decades. For example, in a 10-year study of First Nations Peoples in Central Australia published in 1998, researchers found that connectedness to culture, family and land, and opportunities for self-determination, were likely to be associated with lower mortality and morbidity rates in homelands residents compared to other First Nations NT residents15. In a more recent literature review of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultural determinants of health, the strongest determinants were identified as family and community, Country and place, cultural identity and self-determination, across multiple reviews16. Arts-based cultural expression such as arts and crafts, music, dance, theatre and writing or storytelling have been linked to wellbeing for First Nations Peoples17. Salmon et al explain that by practicing cultural expression Aboriginal Peoples resist colonisation and reclaim Aboriginal spirituality, leading to empowerment, autonomy and wellbeing17.

Methods

The research team employed an ecological mixed-methods research design, including quantitative and qualitative survey and interview data collection, as well as collaborative, data-driven thematic analysis1,4. The ecological approach was used to map a variety of creative practices through a broad range of art forms. Commercial, amateur and subsidised art and creative practices were included in this study and represented the multicultural population of the Barkly (both First Nations and non-Indigenous peoples)1. Arts and creativity in the region were recognised as a complex ecology that saw individuals, businesses, organisations and government working in different ways to sustain culture and contribute to social and economic development4,18.

Participant recruitment and selection

The mapping survey inclusion criteria included respondents who were aged more than 15 years, currently living in the Barkly (the Australian Taxation Office defines this as being for at least 183 days per year) and currently participating in arts or creative activity as defined by our parameters (professional, amateur, voluntary, as well as all art forms and practices listed in the survey, plus self-defined creativity, eg cooking)1. Participants for interviews were selected in consultation with partners – including a major regional arts centre and regional development organization – and through snowball sampling1. Inclusion criteria stipulated that participants possessed knowledge about arts programs being delivered by their organisation (ie in management positions, or involved directly in delivery), or about the overall sector in the Barkly (ie working in a peak body or similar organisation that had an overview of the NT arts sector, and the place of the Barkly within it)1.

Data collection and analysis

Surveys: With the assistance of the project’s partners, the research team undertook extensive in-person surveys with 120 artists in communities across the Barkly Region, as well as sector interviews with 36 key stakeholders and organisations1. This constituted the first cultural mapping of its kind ever to be undertaken in the region. This phase provided significant information about the kinds of activities that Barkly artists and creative workers were involved in and how they were supported by colleagues, communities, organisations and networks in the region1. Based on partner advice, interpreters were not used for survey data collection, which is a limitation of the study.

The survey design for individual artists and creative producers was informed by previous studies done by Throsby and Hollister1,19, involving an economic study of professional artists in Australia from across a range of art forms; and Andersen and Andrew’s1,20 study of artists and cultural industries in the regional Australian context of Broken Hill. Our survey combined multiple-choice and open-ended short- and long-form questions, and therefore resulted in a mix of qualitative and quantitative data1.

Interviews: The research team conducted interviews and consultations with representatives from key organisations within the Barkly arts sector to provide important contextual details. Interview duration was 30–60 minutes, and all were conducted in person except for two interviews conducted by telephone1. Following an informed consent process, all 58 interviewees agreed to be named. A series of 27 interview questions related to topics such as organisational purpose; kinds of activities, programs and services offered; reach; networks and partnerships; and goals, challenges and success factors. Interviewees were also invited to share broader reflections on their work in the Barkly Region1. Based on partner advice, interpreters were not used for interview data collection, which is a limitation of the study.

Data analysis: An iterative process of collaborative and interdisciplinary data coding, analysis and interpretation was used. Descriptive statistics from the survey data were generated using SurveyMonkey’s reporting tools and Microsoft Excel. Data from all phases of the research were imported into the research analysis software program NVivo v11 (Lumivero; https://lumivero.com/products/nvivo) and organised into folders relating to different data types and research phases1. Both open-ended survey and interview data were coded thematically in NVivo to promote integration across data sources and types.

The team provided a draft codebook to project partners, regional stakeholders and the project’s advisory group for feedback before data were coded and analysed. Feedback provided was integrated into the codebook, ensuring that the resulting data analysis would speak to local, national and international priorities and contexts of the study. The team then collectively undertook the coding process, and regularly conducted inter-rater comparison with each other’s work. Finally, the team contracted an NVivo specialist to cross-check the project data analysis and additional data visualisations and matrix cross-tabulation queries. This included identifying patterns across the case studies and generating preliminary narratives within each individual case.

Ethics approval

The research was conducted with approval from the Griffith Human Research Ethics Committee (GHREC protocol number 2016/474) and the Central Australian Human Research Ethics Committee (CAHREC). The research team were required to adhere to the National Health and Medical Research Council guidelines for ethical conduct in human research, and ethical conduct of First Nations health research. Informed consent procedure for all data collection was used, adhering to both the GHREC and CAHREC guidelines. Further to this, the research was governed by the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies Guidelines for Ethical Research in Australian Indigenous Studies19.

Results

Research participants from diverse cultural backgrounds recognised health and wellbeing benefits of arts and creative activity. Arts participation and engagement were reported to have intrinsic health and wellbeing effects for individuals, including mental health and mindfulness, emotional regulation, enjoyment, and relief of physical and emotional pain and stress as well as promoting spiritual connection to self, others and environment. The study indicates that the arts can also shape powerful determinants of health and wellbeing such as employment, poverty, racism, social inclusion, and natural and built environments.

The following sections discuss these findings in relation to two key areas. First, we focus on how the Barkly arts–health ecology featured extensive involvement from health and human service and arts organisations, which provided a strong foundation for inclusive, healing and holistic regional development. Second, we outline how this complex arts–health ecology offered a wide range of benefits, including social-emotional health and wellbeing, cultural and community connections.

Relationship between arts and non-arts organisations in the Barkly arts–health ecology

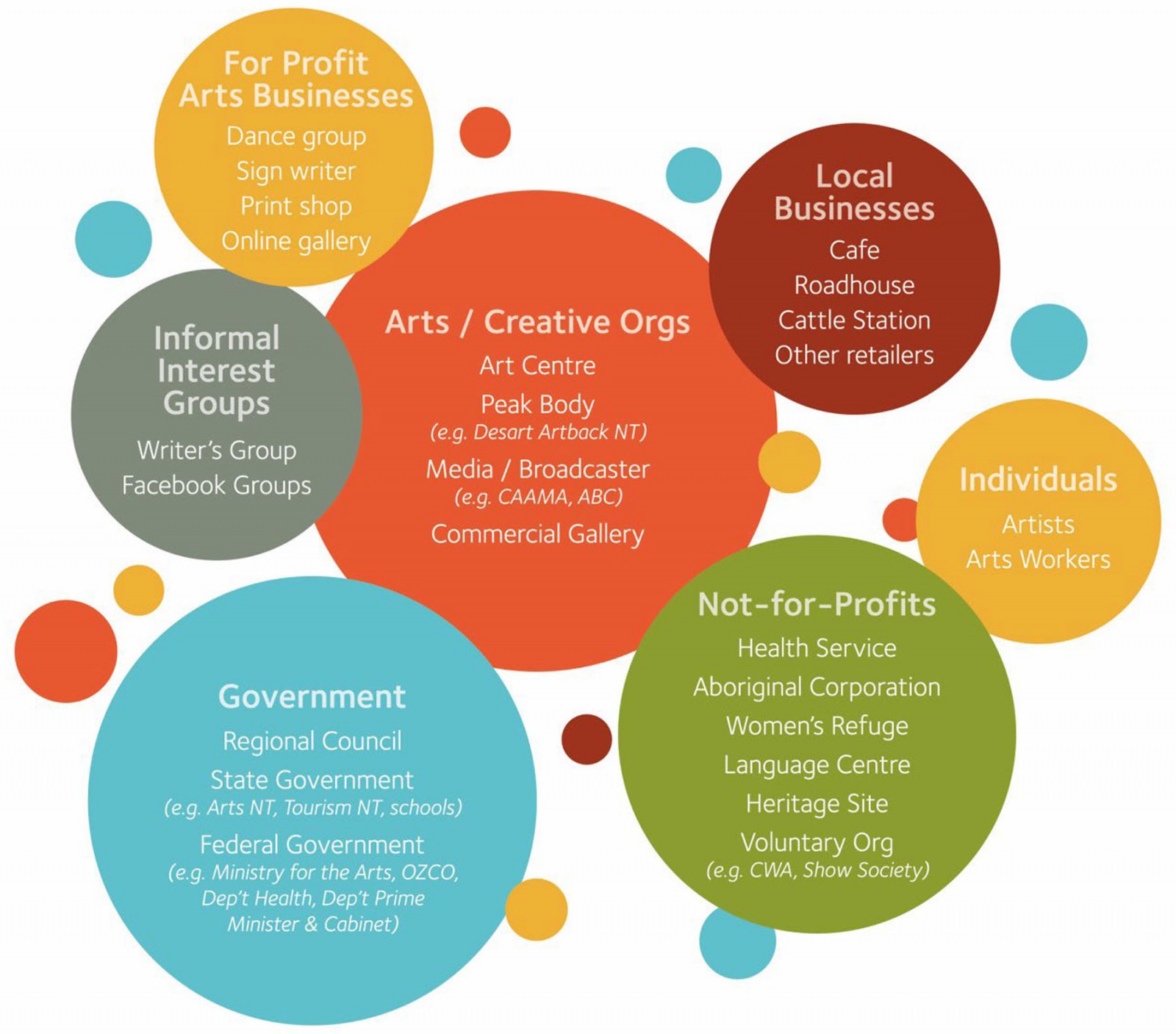

A strong feature of the Barkly arts sector was the involvement of both arts and non-arts organisations in hosting, launching and supporting local arts activities and events. Likewise, arts centres and organisations were often deeply involved in promoting health and wellbeing and community and regional development. Both arts and non-arts organisations were reported as influencing known cultural and social health determinants in this study including connection to culture, identity, language, family, community, Country, income, inequality, safety, social-emotional wellbeing and social cohesion. Hence, we discuss the Barkly arts–health ecology – rather than solely an arts ecology – as the focus of this article. Figure 1 summarises the organisations reported as being part of the Barkly arts sector in this study.

Arts organisations were associated with professional artmaking, major events, sales and cultural maintenance. Those organisations also reported participating in economic, social and cultural activities and health promotion. For example, arts centres reported organising funerals, supporting people to navigate social security and other government bureaucracies, providing food and transport for artists and arts workers and their families, and providing showers and kitchen facilities.

The hybridity and crossover between arts and non-arts organisations in the Barkly arts–health ecology was often attributed to a sense of collaboration and community across different service sectors in the region. That hybridity across different organisations’ missions and activities was also at times attributed to funding availability and the relatively high levels of disability, unemployment and chronic illness in the region, which we explore later in this article. For example, both arts centres and non-arts organisations sought and received National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS) and other welfare-oriented national funding.

A significant number of the health and human service providers who engaged in arts-related work in the Barkly offered disability services or worked with community members who experienced disability. For example, arts sector interviews described successful regional touring projects such as the Good Strong Powerful project, which profiled First Nations artists with disabilities, and local disability services. Well-known Tennant Creek artist Dion Beasley’s work is visible across the region and was cited across the project as an example of a commercially successful Barkly First Nations artist with a disability.

NDIS-funded arts activities were reported as a regular activity alongside accessing health care for some residents of the Barkly region. A total of 8.3% of survey respondents indicated that the disability support pension was their primary income. One of those respondents, Tartakula (Tennant Creek) artist Gladys Anderson, gave the following response when asked about the value of the arts in her life:

I like to do painting because I don’t want to sit in the camp all the time, it makes my body move, make it strong … I paint on Monday, Wednesday and Friday because on the other days I am on dialysis … I like to do painting all the time instead of sitting in the camp. Sometimes I do painting with NDIS. They take a picture and make a postcard of my painting.

Such activities show the often-contingent interplay between arts and non-arts organisations and relationships in the Barkly arts–health ecology.

Distinctions between what was arts centre business, as opposed to non-arts organisation business, often centred on the degree of professionalisation and sale of artworks. For example, Tennant Creek organisation Piliyintinji-ki Stronger Families ran a specialist art project where an artist would work with 15–20 men for around 4 months. The goal of that work was described as ‘therapeutic yarning’ and not specifically designed to ‘generate income’, which was seen as the domain of arts centres. Piliyintinji-ki Stronger Families projects sometimes focused on expressionist painting to depict some of the internalisations and concerns of participants. Men also worked on old mining maps to create protest images against a new mine opening in Tennant Creek. This group subsequently formed the Tennant Creek Brio, which has been winning awards and gaining a profile commercially. Hence, a traversal of health determinants levels is apparent in one program: the men are reportedly achieving individual and interpersonal level social-emotional wellbeing, accessing protective social and cultural engagements, and self-advocating against macro-environmental risk factors (as perceived in the mine reopening). Piliyintinji-ki Stronger Families also reported offering targeted arts programs for women on topics such as foetal alcohol spectrum disorder and healthy eating.

Non-arts organisations reported experiencing some tensions in offering non-commercial, therapeutic arts programs. For example, participating residents sometimes expressed a desire to sell their artworks generated during therapeutic programs, but that was often not supported by the organisation for diverse reasons. One non-arts organisation worker reported that they strongly discouraged the sale of works generated in therapeutic programs to ‘avoid treading on the toes’ of local arts organisations with a remit to support production and sale of local artworks. Existing research has cautioned against ‘flooding’ Indigenous art markets in particular with products of ‘inferior’ quality that may emerge from non-professional or therapeutic art programs21. Although it did not emerge overtly in our data, it is also conceivable that organisations in the local arts–health ecology may deliberately avoid competing with one another for funding. Hence, there are potential tensions and affordances that need to be taken into account when considering how arts and non-arts organisations interact within a complex arts–health ecology.

Figure 1: Organisations reported as being part of the Barkly arts ecology.

Figure 1: Organisations reported as being part of the Barkly arts ecology.

Social-emotional health and wellbeing: Social-emotional wellbeing was one of the most significant outcomes reported in this study. Commonly cited benefits for respondents of all cultures centred on relaxation, stress relief, safety, and relief from distress or trauma. One participant discussed the notion that ‘art was therapy’ that helped them directly but was also something she could do to help others, especially for people with mental health issues. She describes art as a ‘way of healing for the soul and mind’. Another stated, ‘Huge wellbeing value for myself, I have mental health issues and my arts practice helps enormously in mindfulness and general wellbeing’. Other participant responses shared the social-emotional benefits of arts and creativity: ‘[to] keep women sane in remote areas’; ‘helping people in crisis’; ‘a means of relaxing, to calm the kids down’; ‘mental health, pleasure that others get from gifts’; and ‘many a trouble is shrugged off one's shoulders on the dance floor/sand!!’

Kate Foran, former manager of Nyinkka Nyunyu in Tennant Creek, reflected on the level of trauma present in the Barkly region:

There’s no denying the inherent trauma in people when you’re having those sorts of conversations over your morning coffee … it’s just so much a part of many, many, many people. It’s not the exception, it’s the rule. Being traumatised … But the benefits that the arts bring to that, that’s the positive … It is honestly, in my unqualified opinion, just my observation, just the most undervalued mental health therapy going around.

Kate Foran and Josephine Bethel from local Aboriginal corporation T-C Mob both discussed how arts and creative practices were helping communities to alleviate some pain associated with daily grief and intergenerational trauma. As one participant observed:

It’s about despair and depression, you know? I know one family who lost four people this year, and then one of the boys got killed in this latest rollover [motor accident]. How do you deal with that? [Arts programs are trying to] provide people in situations like this something positive to focus on – a ‘happy place’ where they can bring their family and do things they want to do.

Services such as Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation Anyinginyi Health used the arts as a therapeutic program. Catholic Care and the Mental Illness Fellowship Australia NT also used arts programs as a complementary therapy when working with young people and children experiencing social-emotional ill health and other cognitive, emotional and developmental disorders. Some people in the sector expressed concerns about a potential lack of training and expertise in trauma care when delivering therapeutic arts programs; however, we are unable to comment on the level of training facilitators had experienced.

Within the broader subtheme of social-emotional wellbeing, participants indicated that art centres and community spaces used for art making provided a ‘refuge’, ‘sanctuary’ and ‘safe environment’ for artists, away from conflict, family violence, and ‘humbug’ (requests for money from family) and where they could safely discuss cultural matters or issues of concern. Former CEO Alan Murn described in the Creative Barkly Report (p. 1) that Barkly Regional Arts as a safe and reliable space for artists1:

A safe space means that we have a place whereby it’s a respectful place, it’s well appointed, it’s got good [occupational health and safety] facilities. In hot weather, it’s got air conditioning. But it’s a place where there’s always someone on hand to meet and greet visitors, et cetera, to take care of business that is beyond the business of the artists that are working there. Artists and musicians that are working here have a place that is very regular for them, very solid, ever present, reliable and they’re treated respectfully, and they can get a cup of tea, food.

Such quotations highlight the broader role that art centres like Barkly Regional Arts, Arlpwe, Artists of Ampilatwatja and Nyinkka Nyunyu play in Barkly communities in terms of social-emotional health and wellbeing. Studies in other remote communities echo our findings and highlight the role that art centres play in the provision of frontline health and wellbeing services22.

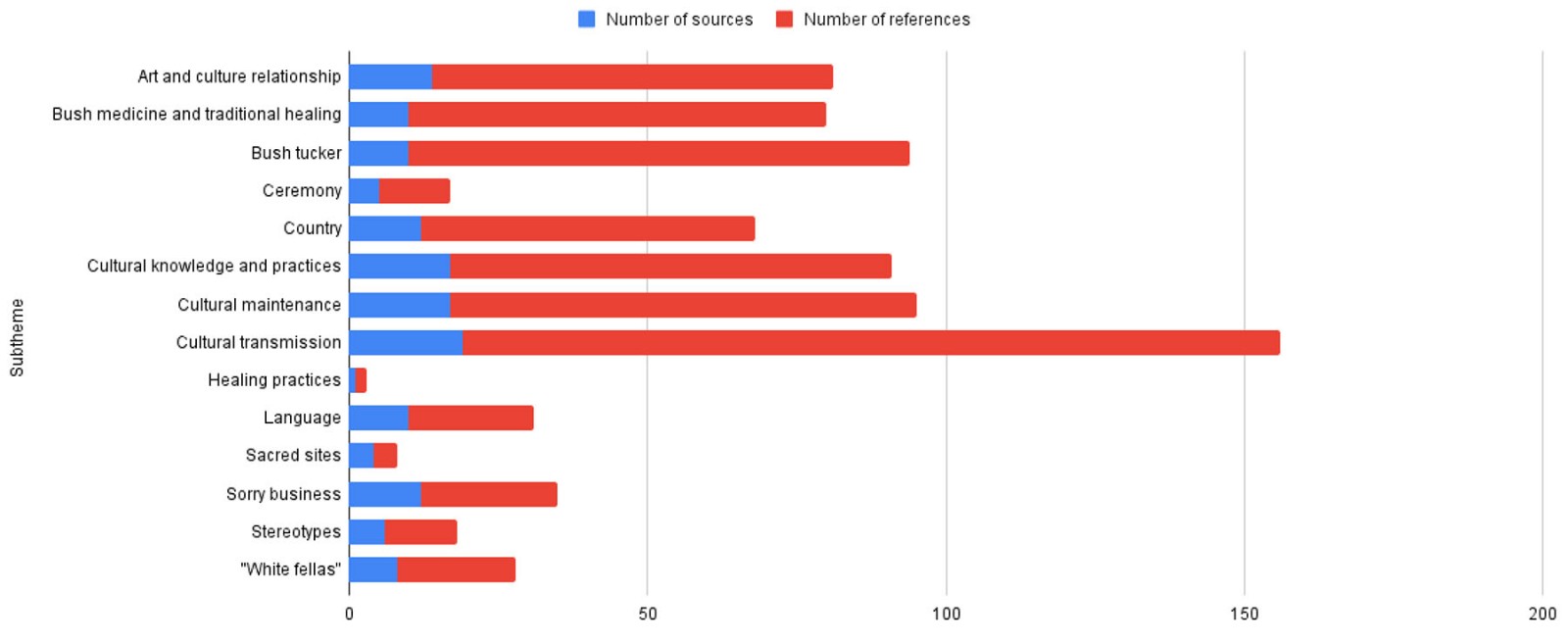

Cultural connection: The study indicated strong crossover between arts and creative practice and connections to culture, which are increasingly recognised as protective factors for First Nations health and wellbeing16,23. The primary areas of crossover between arts and creative practice and culture are reflected in Figure 2, which shows the number of participant responses coded to subthemes under culture. In that figure red represents the total number of references to the culture subtheme across all data and blue represents the number of distinct sources that included reference to that subtheme (eg number of interviews and surveys). Notably, cultural transmission and bush tucker were common features of participants’ experiences of arts and creative practice in the Barkly region alongside bush medicine and healing and other factors depicted in Figure 2.

These findings are exemplified in participant survey responses such as:

I love the painting; love to draw everything; bush tucker because it helps me think about my bush tucker; I work for the church way, and I work in the bush tucker, animals, Toyota and the little car; and the culture way, corroborees, man standing and little boys and the ladies, culture, dancing and the little girls – I paint the little ones being taught the dancing. It’s my relief to work on them. Relief for everything; animals, water, kangaroos, goanna and the birds, crows, brolga, emu, turkey. I paint all those things because I think everything all inside in my heart and mind.

While this quotation emphasises connecting to one’s own cultural heritage, other participants remarked on the intercultural connections made through arts and creative practice and events. Activities such as World Kitchen and Multicultural Night at the Desert Harmony Festivals reflect the many diverse cultures present in the Barkly region1. Organisations including Barkly Regional Arts and Arlpwe Art and Culture Centre contribute to promoting social and cultural connection through learning between different cultures, language groups, local communities, and First Nations and non-Indigenous peoples1,4.

Figure 2: Subthemes relating to the theme of Culture.

Figure 2: Subthemes relating to the theme of Culture.

You can sell everything you want [at the Desert Harmony Festival] like boomerang, painting and all that, it’s good for us Aboriginal mob, make us happy with culture. Artist Camp is good to meet your family, each community’s got its own culture, and when we come together, we can see other people’s business/culture.

Aboriginal art centres and programs providing people with a safe space to spend time, sharing important cultural Knowledges, was a key theme that ran through several aspects of health and wellbeing, as already described.

Fostering positive social connections and providing safe supportive spaces and opportunities for community members to participate in culture and meaningful communal activities promotes a sense of community or social cohesion, which are core components of community development24. Survey respondents also described using creative activities to connect with online networks:

Life on an outback cattle station … bridging the city/country divide by showing that real people live out here in the middle of nowhere. Sharing where their beef comes from and how it is farmed. I am an extrovert living in an introvert’s world so this connects me with people all over the world and helps keep me sane.

Hence, arts and creativity combined provide in-person and online opportunities for social connection alongside potentially significant economic outcomes for the region associated with, for example, tourism, which we discuss elsewhere1. Findings from this study echo longstanding worldwide arts–health research that highlights the importance of community arts practices in community development and building social connection25.

Discussion

Our research indicates that the Barkly arts ecology can be modelled as a unique approach to holistic, inclusive and cross-sectoral health promotion. A distinctive feature of the Barkly arts ecology was the hybridity between arts and non-arts; First Nations and multicultural; government, for-profit, and not-for-profit organisations; and individuals. There was also significant diversity in the forms of value emerging from arts organisations and activities that shape social and environmental determinants of health1. Further, organisations such as the Arlpwe Arts and Cultural Centre clearly pursued cultural and health and wellbeing outcomes across a continuum of determinants of health ranging from healthy eating to community and family violence prevention and cultural tourism1.

This research suggests that the Barkly region arts ecology contributes to a large range of activities and outcomes across health and well-being domains. First Nations run arts organisations together with First Nations artists and leaders are enacting cultural innovation and transmission, leadership and agency, and self-presentation in the Barkly1. Existing structures that support intergenerational cultural transmission and connection in the Barkly Region can support holistic, culturally enabling and community-led development and wellbeing1,26. Study findings indicated that arts activity promoted intergenerational and intercultural transmission and were key strengths of the Barkly Region. Many respondents cited teaching their artform to children and family as a key voluntary activity. Cultural transmission and connection of this kind supports health and wellbeing outcomes for all peoples1,27,28.

The strong cross-sectoral nature of the Barkly arts ecology provides a foundation for arts-led, holistic, healing-centred and sustainable development. There was a productive overlap between the activities of arts and non-arts organisations in the Barkly Region1. This generated a strong, diverse and vibrant local arts ecology that drew on arts organisations resources and expertise alongside those of non-government, for-profit, not-for-profit, health, human services and community organisations that ran arts programs, supported the arts or participated in arts partnerships for community wellbeing1. That degree of overlap and ecological strength provided a foundation for holistic development in the region that attended to not only arts and cultural aspirations but also economic and other social and community goals. Models such as Hearn et al’s value-creating ecologies29, Atkinson and Atkinson’s healing-centred development8, and Fforde et al’s multiform capital asset-based development30 can inform such work.

This study confirmed, though, that regional arts and creativity cannot be seen as a linear path to achieving health and wellbeing1. Indeed, for survey respondents, poor health was the number one factor seen to impede creative practice, and this was compounded by the (largely female-identifying) ageing population of artists in the region. Based on such findings, healing-centred development clearly has a role to play in the Barkly Region. Approaches to healing that are culturally relevant and well resourced will support the region’s strengths and aspirations for development1. It has been suggested that healing approaches that integrate arts can interrupt cycles of intergenerational trauma and suffering1,7. Healing approaches that promote community connection and wellbeing can offer a foundation where other forms of development can occur.

For these approaches to be effective, they must incorporate structural considerations that tackle social and environmental determinants such as education, inequality, poverty, employment and racism1. Negative social determinants of health such as violence, exposure to substance abuse and extreme poverty were common experiences of artist participants1. In many cases, arts centres and organisations were engaged in seeking community solutions to these issues. This study confirmed that arts were a protective factor to negative social determinants of health by providing a source of relaxation and ‘refuge’1.

Limitations and directions for future research

Study limitations centre on the use of English language in data collection in a region characterised by intense cultural and linguistic diversity. Data analysis was largely conducted by non-residents in the Barkly region, which may have limited interpretation of data and findings. Comprehensive recommendations for policy, practice and funding arising from this study are provided elsewhere1. Overall, we recommend that further arts–health research is undertaken and resources invested into research that explores the full potential of ecosystemic and holistic approaches to health and wellbeing1. We recommend that further research into the value of arts ecologies in remote regions must be measured and developed using complex interdisciplinary approaches. This includes, in particular, health economists, social and cultural geographers, creative and cultural industries researchers, human services and social work systems theorists, human rights scholars and holistic regional development specialists1. We articulate elsewhere the particular need and opportunity for valuing and developing regional arts–health ecologies drawing on First Nations cultural knowledges and practices5.

Conclusion

This study confirms and extends previous research that highlights the vital role of arts organisations in promoting health and wellbeing in remote and very remote regions. The study has intense significance in mapping the relationships and affordances of intersectoral collaboration in health and wellbeing promotion across arts and non-arts organisations. This has significant ongoing implications for how both arts and health are conceptualised and funded in the Barkly Region and elsewhere.

Importantly, from a First Nations standpoint in particular, this study confirmed how arts and creative activity contribute to holistic regional development in the Barkly and potentially many other remote and very remote regions region. Arts and creative activity were reported to have intrinsic health and wellbeing effects for individuals, which included mental health and mindfulness, emotional regulation, enjoyment, and relief of physical and emotional pain and stress as well as promoting spiritual connection to self, other and environment1. The study confirms that the arts activities can shape powerful determinants of health and wellbeing such as employment, poverty, racism, social inclusion, and natural and built environments1. Of further policy significance is the finding that remote and very remote artists and arts organisations are working to provide communities with opportunity for healing-based arts programming and support. Further interdisciplinary approaches, and those founded on First Nations knowledges and practices in particular, would ensure trauma informed and culturally safe principles are promoted through music, arts and creative cultural activities.

Funding

This study was funded by the Australian Research Council (project ID 212890711).

Conflicts of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

You might also be interested in:

2007 - Pharmacists' views on Indigenous health: is there more that can be done?