Introduction

Indigenous Peoples, compared to non-Indigenous Peoples, have poorer access to health care, are more likely to live in ill health and have lower life expectancies at birth1. There is no one accepted definition of Indigenous Peoples due to their diversity, but the UN highlights the importance of self-identification and acceptance by their Indigenous community as one of the key elements to Indigenous identity and ethnicity2. Other key aspects include relationships to their lands, traditions, resources, territories, culture, language and ancestors3. Globally, there are approximately 476.6 million Indigenous Peoples representing 6.2% of the world’s population, with approximately 97% of Indigenous Peoples living in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs)3. High levels of poverty, discrimination and marginalisation are evident; this is especially the case for Indigenous women, who may be faced with inequities because of the intersection of being both a woman and Indigenous3.

In relation to access to maternal health services, defined as services for antenatal care, postnatal care and childbirth, a previous integrative review found numerous barriers for Indigenous women in LMICs and highlighted the need for more research on access issues in relation to delivery and postnatal care4. These barriers included the 'top-down nature' of interventions, a lack of cultural awareness from providers, language barriers, cost, poor awareness of services, and geographical barriers such as distance and transport4. It is timely, given the WHO aim of ‘leaving no-one behind’ by achieving Universal Health Coverage (UHC) by 2030, to undertake another review to explore how far the identified barriers to access remain and to describe, using contemporary research, any further barriers that have been identified. This is important as it has been highlighted how initiatives such as UHC with their focus on ‘financial risk protection, access to quality essential healthcare services, and access to safe, effective, quality, and affordable essential medicines and vaccines for all’5 ‘do not reflect the realities faced’ by Indigenous populations where social exclusion and marginalisation make it more likely they will receive poor quality services6. Moreover, indicators that track UHC, for example service coverage indexes7, do not effectively consider within-country inequalities and differences in coverage of and access to health services between different groups. For example, Thailand’s high service coverage index obscures differences in access to health services between Indigenous Hill Tribes and the rest of the population, with poverty, lack of citizenship, social exclusion, marginalisation and discrimination impacting on Indigenous Peoples’ access to health services8. This is compounded by the lack of data on Indigenous Peoples’ health and needs2. Reviewing the updated literature on Indigenous women’s access to maternal health services will further illustrate the specific issues that face Indigenous women and may also be of relevance to other marginalised groups in rural and remote settings, including nomadic peoples.

Access to health care

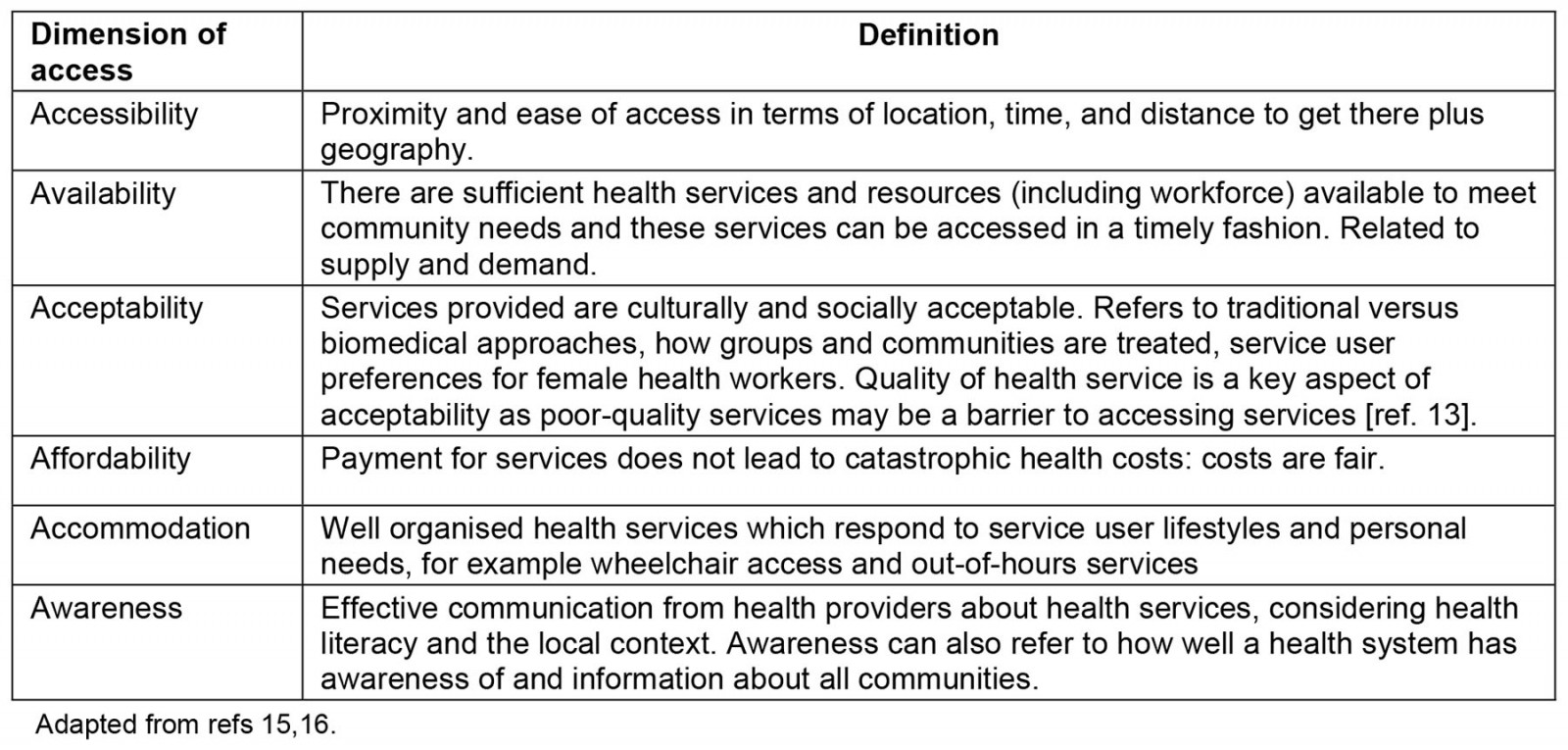

Improving access to quality health care, to achieve ‘health for all’ through UHC, is said to be one of the objectives of all health systems9. However, defining what is meant by access to health care is open to debate; with several different models of access apparent10,11. Access is often linked to the performance of health systems10, and the term may be used interchangeably with concepts such as ‘coverage’. However, understanding the factors that impact on access to health services often goes beyond a focus on coverage in relation to numbers of people reached (population coverage), the range of ‘essential’ services offered (scope of coverage) and breadth of coverage, which includes factors related to out-of-pocket costs12. Access also relates to potential barriers to the delivery of services, including whether services are person-centred; whether there is an understanding of the user experience; the quality of services provided; and services being responsive to the social, cultural and health needs of communities10,13,14. Penchansky and Thomas define access as ‘the degree of fit between the clients and the system’15 and theorised a taxonomy of access to health care that contained five dimensions (affordability, accessibility, availability, accommodation/adequacy and acceptability). This was extended by Saurman to include a sixth factor (awareness) (Table 1)16. These domains of access are said to be interconnected15 and the targeting of one domain may not necessarily bring about significant improvements in access to health services. For example, the introduction of health insurance, which targets affordability, may not necessarily mean that women will access maternity services if the services that are offered are culturally unacceptable; conversely, the availability of health services is of no good if no-one can afford to pay for them.

Given the difficulty in defining access, Saurman’s16 and Penchansky and Thomas’15 models of the six dimensions of access to health services offer clarity and are utilised in this integrative review as a conceptual framework.

Table 1: Conceptual framework: dimensions of access13,15,16

Methods

An integrative review that followed a systematic process was undertaken to explore and evaluate the extent of the published literature on Indigenous women’s access to maternal health services in LMICs from 2018 to 2023. Integrative reviews enable a range of diverse research designs and methodologies to be integrated in a search for literature17 and can inform evidence-based practice as well as develop or test theories18. The review followed Whittemore and Knafl’s five-step framework for integrative reviews, which focused on problem identification, a literature search, data evaluation, data analysis and presentation of findings19. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines were also used20. The protocol for the integrative review was registered on Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/gxkfz) and there were no deviations from the protocol.

Problem identification

The research question was developed following the ‘participants, concept and context’ (PCC) approach:

- P (types of participants): Indigenous women

- C (concept): factors impacting access to maternal health services

- C (context): low- and middle-income countries

The research review question was ‘What are the factors that impact on Indigenous women’s access to maternal health services in LMICs?’

Literature search

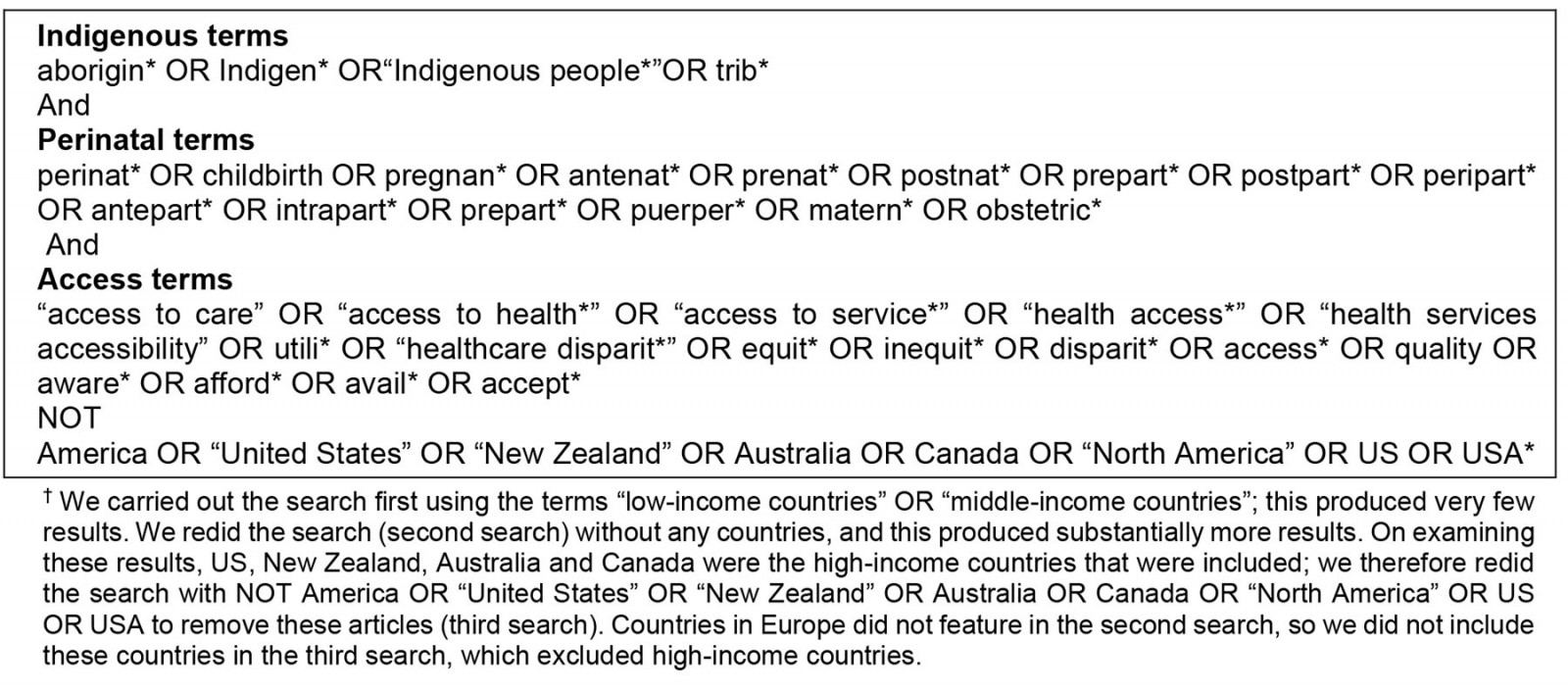

We were interested in all published empirical studies that focused on the research question, and we searched the following electronic databases: Academic Search Premier, MEDLINE, Psychology and Behavioral Sciences Collection, APA PsycInfo, CINAHL Plus with Full Text and APA PsycArticles (through EBSOhost). The search was performed on 16 January 2023 for articles published between 2018 and 2023. All articles that were retrieved were transferred to Endnote and duplicates removed. Table 2 outlines the search terms.

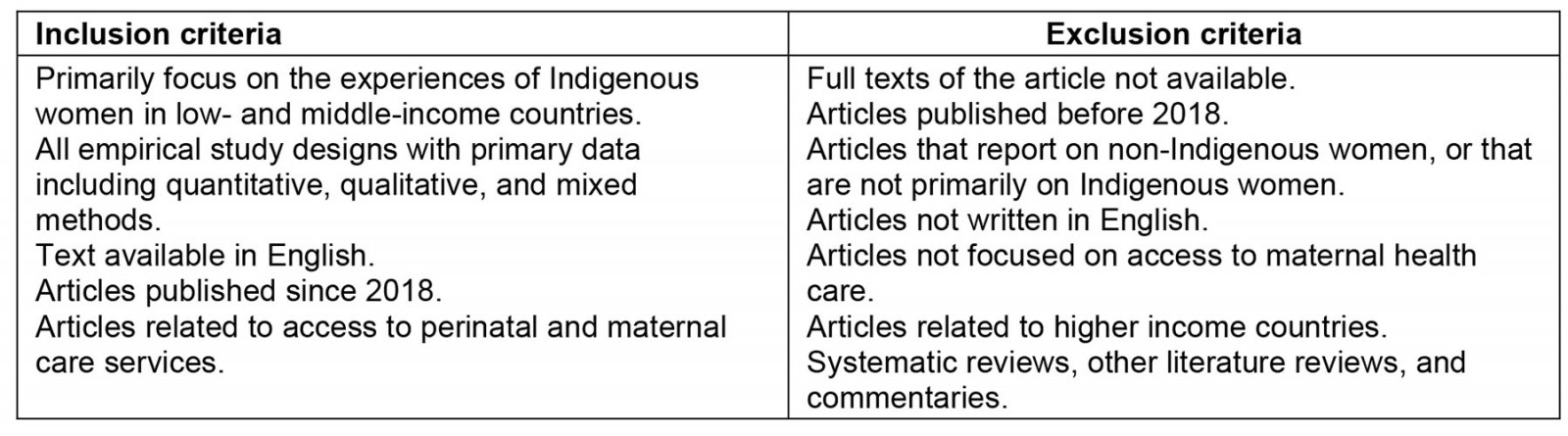

Two researchers independently screened abstracts and titles for eligibility. Full texts were then screened to identify the final articles according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria (Table 3). The two researchers reviewed each other’s abstract/title and full-text screening, and reached consensus, through discussion, regarding which texts should be excluded and which should be included.

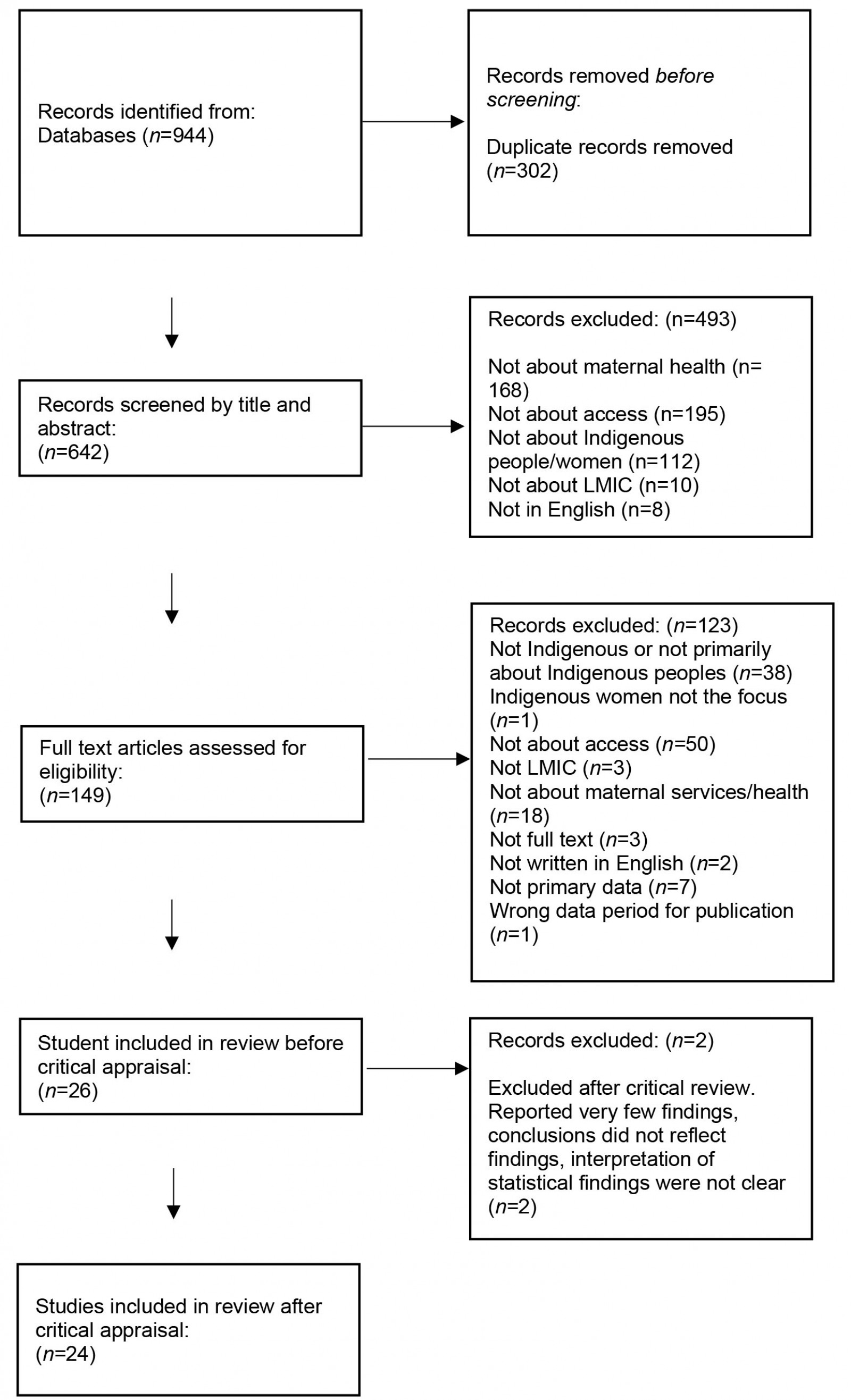

The PRISMA diagram in Figure 1 outlines each stage and the reasons for exclusion.

Table 2: Search Terms

Table 3: Literature review inclusion and exclusion criteria

Figure 1: PRISMA diagram for literature review.

Figure 1: PRISMA diagram for literature review.

Data evaluation

A total of 26 articles underwent critical appraisal independently by the two reviewers, with disagreements negotiated using CASP Critical Appraisals Tools (CASP)21. CASP, however, does not have critical appraisal tools for cross-sectional studies nor quasi-experimental designs and in these instances Joanna Briggs Critical Appraisal Tools (Joanna Briggs Institute)22 were used. Where methods were mixed, we utilised the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT)23 because it considers the specific nature of mixed methods. Two articles did not meet critical appraisal quality standards for the following reasons: conclusions did not come from the results, there was unclear interpretation of the statistical findings and very few results were evident. These two articles were not included, and this resulted in 24 articles in the final review.

Data analysis

The final included studies (n=24) were then read again, and two researchers independently and manually extracted information from the articles, which was presented in a matrix. Data extracted were then compared and negotiated by the two researchers. The following information was extracted: authors/date/title, theoretical/conceptual frameworks, research aim(s)/question/hypothesis, study design, methods/analysis, demographics/sample/setting/country, accessibility findings, availability findings, acceptability findings, accommodation findings, awareness findings and study limitations. The dimensions of access conceptual framework were utilised in the matrix as a conceptual framework15,16.

Presentation of findings

The findings were analysed, thematically, in relation to the dimensions of access conceptual framework. Thematic analysis of the extracted data was undertaken independently by the two researchers, and results were discussed and compared.

Results

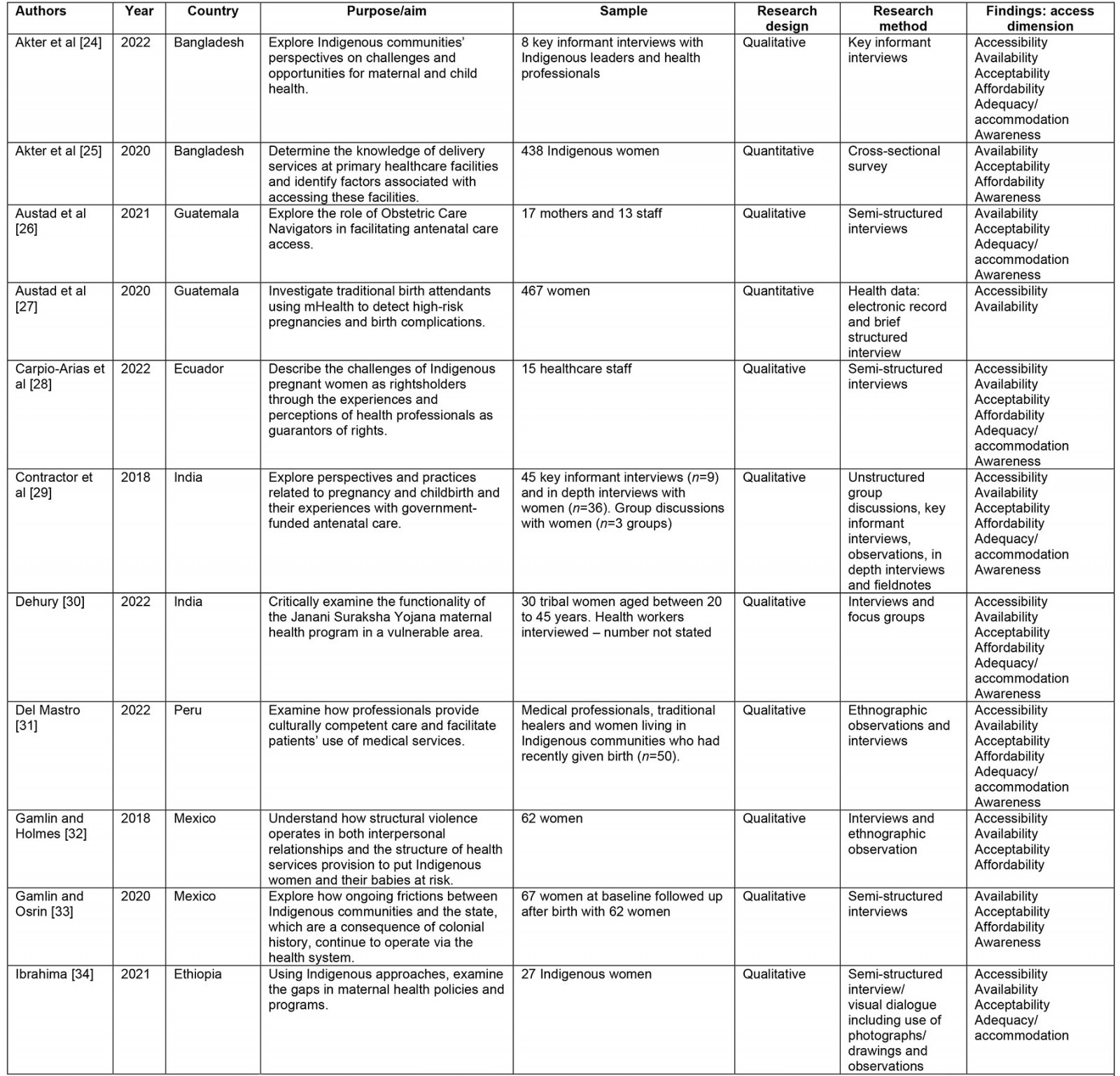

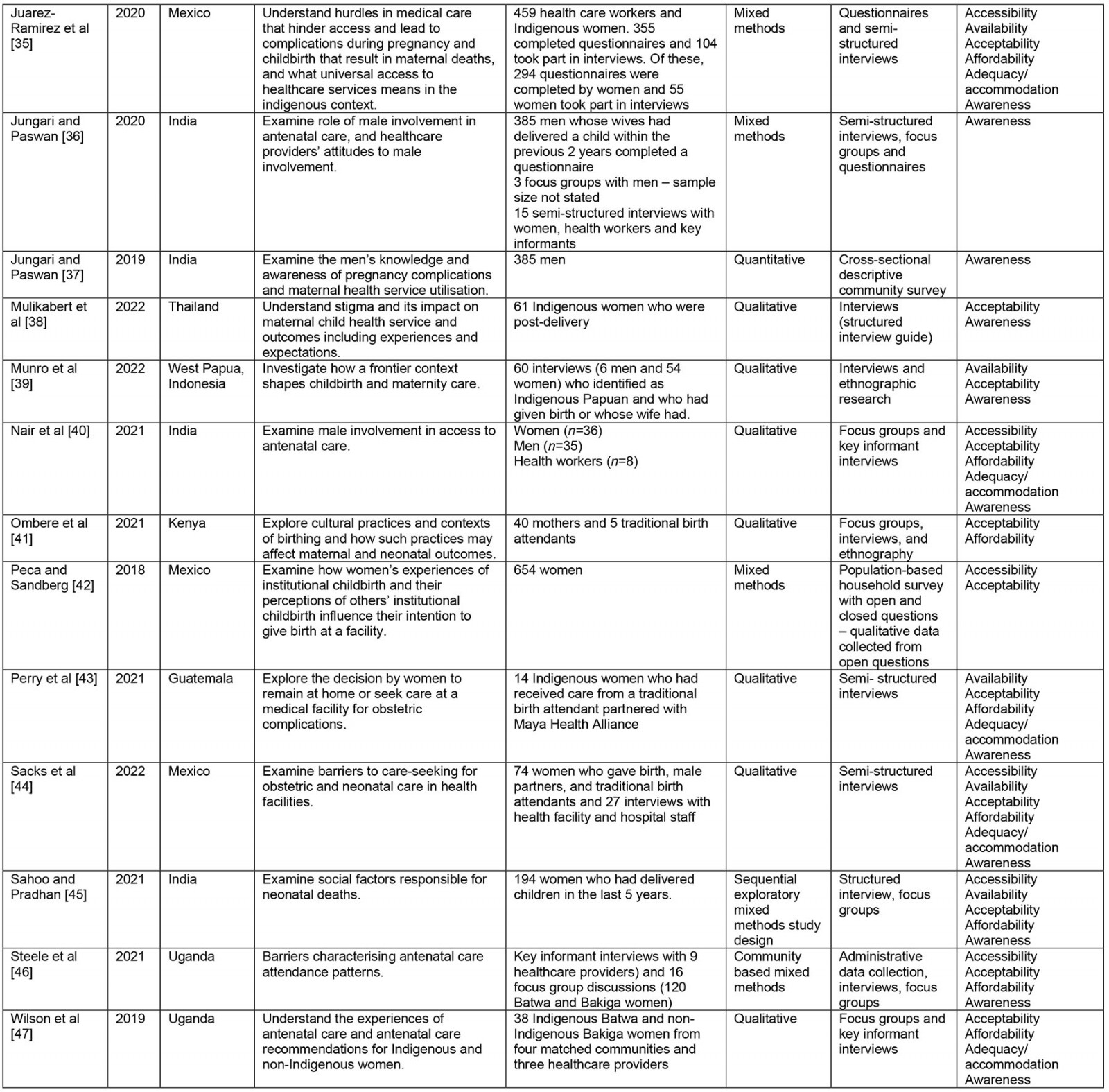

A summary of included studies is presented in Table 4.

Table 4: Description of included studies

Description of included studies

Of the regions where the studies were conducted, the largest number of studies (10) took place in Asia – India24-29, Bangladesh 30,31, Thailand32 and Indonesia33 – and the Americas: Mexico34-38, Guatemala39-41, Peru42 and Ecuador43. Four studies took place in the African region: Uganda44,45, Ethiopia46, and Kenya47. Sixteen articles reported using qualitative methods (Table 4), three articles used quantitative methods and five articles used mixed methods. The most common research methods reportedly used included focus groups, key informant interviews and ethnographic observation, and the participants included women, family members and healthcare providers. Overall, there was a lack of good quality quantitative studies, and those studies focused on the African context.

Thematic analysis

The following section explores the main findings for each of the six dimensions of access.

Accessibility: The most common barrier to maternal health care access related to accessibility was distance from the facility, which was cited by 14 of the 24 articles24,25,28-30,34,36-38,40,42-44,46. While distance was the most cited barrier, issues associated with large distances from the facility were the lack of availability and affordability of transport to the facility. Lack of accessible or affordable transportation was cited by six articles28,30,34,36,38,46 with the cost of transportation to a health facility often being prohibitive38,44. Some authors also reported that, even when government-funded transportation was provided, ambulance drivers often asked for fees to utilise the ambulance29. Other barriers related to distance from the facility were the loss of wages and time due to travelling25,38,43. One study also found that women may be reluctant to travel long distances because of a fear of giving birth while in transit46. Armed conflict preventing travelling38, or needing to walk long distances30, were also barriers. While women might try to overcome the barrier of distance by staying close to the facility prior to giving birth, including in maternity homes/rooms (which will be explored later), the accommodation costs associated with this meant it was not always feasible34. Barriers to accessibility were often heightened for Indigenous migratory women, internally displaced Indigenous women and Indigenous women in very remote areas25,29,30.

There were some facilitators that would overcome the barriers according to accessibility. Providing transportation or having healthcare workers cover the cost of the transportation upfront40,42 to overcome accessibility barriers was reported as a potential solution. Moreover, some healthcare workers explained that they gave priority and earlier (in the day) appointments to women travelling long distances to help make it easier for them to attend facilities, and in some cases would pay the costs associated with travel up-front42. Improving geographic and economic access38 and providing more support by healthcare providers40 were also cited as facilitators, as well as living closer to the hospital34,37,44.

Availability: Sixteen articles focused on the availability of maternal health services for Indigenous women. Of those 16 articles, 1125,29,30,34-36,38,39,41,43,46 highlighted a lack of facilities in rural primary health posts/community clinics/referral centres, which were often not equipped to carry out antenatal tests or support childbirth. This resulted in an increase in home visits or referrals to other health centres, which were often a considerable distance away. Lack of facilities included no water or electricity to run refrigerators for medication as well as buildings with cracks and mud floors, which enabled snakes and rats to come into the facility – all of which impacted on women’s attendance and their perceptions of the quality of services30,46. Other articles highlighted limited physical space, which meant that women were unable to have birthing companions present38; shortages of equipment, such as ultrasound machines and laboratory testing facilities; and necessities such as medicines, gloves, bed linen, towels, gowns and cleaning supplies35,36,46.

Twelve of the 16 articles24,25,29-31,34,35,38,40-42,46 highlighted issues with the availability of staff. These included staff not being in the facility on the days that they should have been, even when women had appointments, and medical staff shortages including a lack of skilled birth attendants, community care providers and staff with specialist skills23,25,35,38,41,46. Absent staff and staff shortages impacted on women’s trust in the facility and contributed to long waiting times29,38. In some cases, health workers had to travel with women who were being referred to other health centres, which resulted in no cover in the local health centre42. When this did occur, staff reported having to pay for their own accommodation as well as the cost of fuel to transport their patient. Terms and conditions for medical staff in rural posts were also highlighted as being problematic, which contributed to staff leaving and staff shortages34. Staff training and the availability of trained staff were also an issue, with health staff such as Accredited Social Health Activists giving out poor advice25 and traditional birth attendants, because of limited medical training and knowledge, being unable to recognise, refer and manage maternal health complications46.

Acceptability: Twenty-one articles reported acceptability barriers to accessing maternal health services24,25,28-39,41-47. This included a lack of fit between the biomedical procedures offered in health facilities and community cultural, social and religious traditions around childbirth. For example, women were apprehensive about using antenatal care services in case their spirits were displeased and reported beliefs about the predetermined nature of death, putting their faith in God to protect them during childbirth46. In addition, women reported that their pregnancy outcome would have not been any different if they had attended the facility41, with beliefs such as ‘evil eye’ resulting in visits to traditional healers before visiting the health facility29, leading to delays in accessing emergency medical care. This meant that for many women the biomedical construction of childbirth and the services offered were not seen as aligning with their expectations.

Moreover, there was limited engagement from maternal health services, with community preferences for traditional healers and home births rarely incorporated into the biomedical health model25,29,42. Many of the practices in health facilities did not fit women’s cultural understandings of acceptable birthing practices such as the use of horizontal as opposed to traditional Indigenous vertical birthing positions, not being allowed to have their relatives in the room and being denied the use of other cultural traditions such as incense, herbal teas, special foods and rituals around the placenta38,44,47. Moreover, previous experiences of what was perceived as poor-quality care were reported, including a lack of physical support, with women being left alone during childbirth, which was seen as significantly different to the care that they would have received at home with their family38,41. Fear of surgery and being away from other children, family and work meant that home birth was preferred to facility birth in many cases, and concerns were raised about who would look after their children or households if they were away from home41. In addition, the use of male health practitioners was problematic and made women embarrassed and fearful of using health facilities32,46. The limited responsiveness to the women’s cultural needs and lack of involvement of the communities in planning and designing services made it more likely that women would give birth at home so that they could have the birth that reflected their cultural and spiritual beliefs as well as Indigenous identities.

Another factor identified was that of obstetric violence arising from obstetric racism33. This resulted in women being treated poorly by staff, including a lack of respect shown towards them, verbal abuse and neglect28,32,41,44. It was reported that women were left in pain, shouted at, slapped, not listened to, humiliated and threatened, and had procedures (such as caesarean sections, episiotomies, and sterilisation) that they had not consented to24,30,33-35,38,39,47. Poor treatment was also evident, with bribes for treatment being requested for services that should have been free29,30,37. Some women stated that staff had intentionally tried to harm them by giving them the wrong dose of medication38,45. All of this contributed to a lack of trust between women and healthcare facilities, with quality of care being seen as poor and thus unacceptable.

Affordability: In total, 16 articles24,25,28-31,34-36,38,41-45,47 had factors relating to the affordability of maternal care. The most common identified barrier was needing to pay additional costs to receive health care that they could not afford, cited by 13 articles25,29-31,34,35,38,41-45,47. Within this group of articles, paying additional costs for medication was a barrier25,30,41,43,44 as was paying costs for additional services such as unexpected surgical costs25,31,38,47 or needing to pay bribes to healthcare staff to stay at facilities or receive care29,30. Participants also described needing to pay out-of-pocket costs such as paying for food and/or accommodation30,34,35,42,44,45, needing to pay for transportation to and from facilities30,31,34,35,38,44,45 and the issue of potential wage loss occurring if they and their partners attended antenatal services away from their homes28. Some participants also discussed the additional costs (such as food, accommodation and/or transportation costs) of paying for family members to accompany them to a facility to give birth28,30,34,35. There were a few cases where services were provided at reduced or no costs to patients, either by the government services or a non-governmental organisation24,36.

Accommodation: Twelve articles reported barriers to maternal health services accommodating the needs of Indigenous women24,25,28,30,36,38,39,41-43,45,46. This included the limited opening hours of services, for example in some cases facilities open between 9 am and 3 pm, which was not conducive to women and men working25,28, and services that were not open all the time or during bank holidays30,38,46. However, there were also reports of staff changing the opening hours to accommodate the community and medical staff undertaking non-clinical roles to alleviate barriers to access42. Language was also an issue as well as a lack of Indigenous staff, with many of the staff not being able to speak Indigenous languages, which increased confusion and made communication including sharing of information difficult30,39-41,43. This was exacerbated in many cases by a lack of interpreters. However, in some cases there were reports of Accredited Social Health Activists24 and other community health workers39 who spoke a range of languages, and this was said to facilitate a better understanding of the hospital regime and enable the women to ask questions, bringing about a reduction in their fear. Women reported feeling ‘shame’ and feeling ‘ignored’ for speaking an Indigenous language and not being able to speak the dominant language of the country38.

Services were also said not to accommodate the cultural needs and preferences of Indigenous women, with inappropriate food being offered in the hospital as well as culturally irrelevant guidance and practices43, with little attempt made to facilitate the women’s cultural preferences24. When staff did attempt to make dietary recommendations relevant to Indigenous women, lack of money often precluded the women from following these instructions45. Moreover, the distance that women had to travel was also not considered by staff, and women were turned away from the hospital late at night because they were not yet ready to give birth; this resulted in several cases where women gave birth on their way home by the side of a road38. Maternity waiting rooms may have overcome this situation36. Community views were not considered in the planning and design of maternal health services, and co-production of services was felt to be key to improving access to services30.

Awareness: Nineteen articles reported that women (and their partners, including relatives) had limited awareness of the range of maternal health services available, including the benefits of these services24-33,35,36,38,39,41-45. Minimal knowledge around referrals, the purpose of maternity waiting rooms, that services were free, and what would take place during procedures was apparent, with women unsure about why their stomachs were being pressed during antenatal examinations and fearful that this would kill their baby24,29,30,38,44. Moreover, it was reported that women were not told about the benefits of nutritional supplements during pregnancy, with some women discarding the supplements they were given43, as well as fears and a lack of information around episiotomies35 and caesarean sections30, which led to women avoiding the facilities41. This limited awareness may have been related to the lack of interpreters, including poor communication, but may also have been a result of the minimal respect shown towards Indigenous women and the primacy of the biomedical model where medical staff ‘know best’. Moreover, women and their families tended to view maternal health services as being curative (provision of medicines) rather than about preventative care45, and this was exacerbated by a lack of communication or mixed messages from health professionals, including health promotion ‘cues to actions’ about why preventative care was needed in pregnancy. This often resulted in women accessing services in emergency situations. Where health professionals did communicate information in an appropriate way – which considered literacy levels, language and was culturally sensitive, including relating preventative care to cultural ideas of safety – this was found to be empowering39,42, but this information was not always taken up by the women if they could not see the relevance to their lives30.

Women thus often relied on information from other women, including older women who had previously given birth but who may have had limited experience of hospitals and antenatal care25,44. The inclusion of men, community leaders and older women was said to be important in awareness-raising as studies identified a lack of empowerment of women, with decisions about the acceptability of health facility care being made by men, other family members or older women25-28,41. Insufficient communication and lack of awareness, therefore, was said to have led to poor pregnancy risk evaluation on the part of women and their communities, with pregnancy being equated with positive outcomes where there were minimal complications29. This resulted in pregnancy and issues such as oedema, headaches and high blood pressure being seen as ‘routine’ occurrences that did not require medical intervention30,41. While most of the articles focused on the lack of awareness of the women and their communities, it was reported that health providers had minimal knowledge of and training on Indigenous cultures and ‘intercultural adapted childbirth’43, and awareness of the needs of migrating Indigenous women was poor25.

Discussion

This integrative review utilised a conceptual framework15,16 of the six dimensions of access: accessibility, availability, acceptability, affordability, accommodation and awareness to explore Indigenous women’s access to maternal services in LMICs. Barriers were found to exist across all six dimensions, and interventions should target all six dimensions due to the interconnected nature of these access barriers. This integrative review confirms the findings of a previous review4, with the same barriers to accessing maternal health services remaining for Indigenous women. Moreover, it adds to the previous integrative review by showing how obstetric violence, lack of support from health professionals and abuse, as well as the biomedical nature of medical interventions, were a barrier to access. Additional payments (bribes) for services were also an issue, as was loss of wages in relation to accessing services. A focus on maternity services as curative rather than preventative was also of note, as was a lack of health professionals’ knowledge of Indigenous cultures and childbirthing preferences.

Recommendations to improve access to maternity services for Indigenous women in LMICs include culturally sensitive and appropriate health literacy education that supports community understandings about service availability, free services and need for services including the importance of preventative care27. Targeted promotion of antenatal care and postnatal care by trained Indigenous healers/workers to build relationships with communities as well as more respectful co-working between traditional birth attendants and medically trained practitioners are also needed 46,48. This could include the use of Indigenous advocates who can support women in accessing services to overcome fear, misunderstandings and language barriers39,40. The use of community waiting rooms that are responsive to women’s cultural needs and the updating of poor facilities (including lack of essential medicines) within community health facilities are recommended. Terms and conditions of staff in Indigenous areas need to be reviewed to attract and retain staff, including budgets for transportation and accommodation when transferring women42. This should be coupled with poverty reduction initiatives to support women in accessing services, including the provision of emergency transport and payment for loss of earnings when accessing services25. Outreach services to reduce transport, childcare and geographical issues and improve access to antenatal care and postnatal care within the community are needed, especially in the remotest communities42,44. The use of mobile technology43 and other methods of media communications31 may be an asset in relation to health promotion text reminders and for raising concerns about possible complications.

Services need to ‘think’ Indigenous to ensure that they are responsive and accommodate the needs of communities. This includes the integration of traditional Indigenous birthing practices into the biomedical birthing model that are co-produced with Indigenous communities24,25,30,47, including birthing centres run by trained traditional birth attendants46 and recruitment of Indigenous staff. Increased training of health professionals on Indigenous cultural norms and traditions – including the importance of ancestral knowledge, birthing practices, respectful and non-abusive maternal care and improved cultural competency – is required29,36,37,44, including the role of intercultural partnerships48.

Interventions need to be situated within a model that focuses on reducing the social exclusion and marginalisation of Indigenous Peoples, as access barriers often reflected the ongoing and historical discrimination, stigma and structural disempowerment that Indigenous Peoples face6. This was apparent in the lack of understanding about why Indigenous women did not use the facilities, and little attempt being made to explore why this was the case, with a deficit model of Indigenous cultures and peoples being evident. For example, health professionals reported that women often did not ask questions, with this being seen as a deficit in the women as opposed to a health system that was not responsive to the sociocultural and linguistic needs of Indigenous women43. Moreover, the introduction of policies that call for ‘intercultural birthing’ or strategies such as the WHO Traditional Medicine Strategy 2014–2023 are not enough if there is weak institutional support and training; the stigmatisation of traditional medicines, within a biomedical model, is a barrier to implementation42,49. Hence interventions need to not only reflect the sociocultural needs of Indigenous Peoples, including empowering Indigenous Peoples to be partners in the planning of appropriate services, but also actively challenge the marginalised and stigmatised positioning of Indigenous Peoples and their cultural knowledge. Without a focus on the latter, the aim of achieving UHC for Indigenous Peoples and improving access to health services may not be realised5.

Limitations of this integrative review include the possibility of missing articles, as it was sometimes unclear from the articles whether a particular group was from an Indigenous community. This was especially the case in relation to the term ‘tribal’ and sub-Saharan Africa and the use of ‘caste’ as a descriptor in Nepal. To try to mitigate this, we researched any groups concerned and followed up with Indigenous global organisations.

Furthermore, the exclusion of literature written in languages other than English meant that the review did not cover the full breadth of literature. This is potentially problematic as some literature on Indigenous women in LMICs was written in languages other than English.

More research on access to services in the postnatal period is still needed, as well as quality quantitative research. This could include a focus on the impact of COVID-19 on access to services for Indigenous women as well as the impact on outcomes for women and neonates 50.

There is a lack of research on Indigenous groups in North Africa and sub-Saharan Africa including groups such as the San and other hunter-gatherers. Moreover, there is a lack of research on Indigenous groups in South-East Asia including Cambodia, Malaysia, Myanmar, Philippines and Laos. In South America, a paucity of research in Brazil and Bolivia is of note.

Lastly, it is evident that more evaluations and research on successful interventions in LMICs that have improved access to maternal health services for Indigenous women, including interventions to empower communities and reduce social exclusion, are needed as well as research on workforce development initiatives in LMICs that aim to promote intercultural education and practices.

Funding

The authors report no sources of funding.

Conflicts of interest

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.