Introduction

Around 40% of the population in South Africa live in rural areas. Despite carrying a disproportionate burden of disease, rural communities experience greater barriers to accessing health care than urban residents1. The responsibility for rehabilitation services in rural and underserved parts of South Africa frequently rests on a group of novice practitioners completing a year of compulsory community service after graduation. Community service for health professionals is a human resourcing strategy implemented by the South African government two decades ago to strengthen public health services in rural and underserved settings2. The strategy has proved to be an effective recruitment strategy3, substantially increasing the number of occupational therapists and other rehabilitation personnel in the public health sector4.

Community service does not, however, significantly improve retention of staff in rural and underserved areas3. The annual turnover of this staff cadre presents challenges to service continuation and expertise retained within these services. Inadequate management, support, and supervision3,5,6 have frequently been reported. In a study of occupational therapists who completed their community service in 2013, 65.9% (n=60) reported dissatisfaction with supervision5. In a smaller 2019 sample of community service occupational therapists, 40% (n=30) were dissatisfied with supervision and a further 22.7% (n=17) did not have a supervisor, suggesting minimal improvement in satisfaction between the two studies. The latter also suggests an increased vulnerability to burnout: therapists who were dissatisfied with supervision or reported minimal social support were more likely to report emotional exhaustion as one of the three components measured for burnout (p=0.02 and p=0.01 respectively)6.

Understanding the typical practice characteristics of community service occupational therapists provides some context for their vulnerability and need for support. These therapists are young novices (usually aged 23 years), navigating the transition to clinical practice5,6, for which they are typically required to relocate5. Most of these therapists are placed in underserved settings5 where services are underdeveloped or where they are the only occupational therapist. Around 40% of therapists are placed in rural settings for their first year of practice. This may also be the first exposure to rural practice5,6 for those therapists who complete their community service in rural areas. Occupational therapists with experience are known to typically move out of public health services into South Africa’s private health sector after gaining a few years of experience within state services, which has detrimental effects on service delivery7.

Community service occupational therapists typically work in a generalist capacity, intervening across multiple areas of occupational therapy practice. One area of practice that these novice therapists have reported as being challenging is hand therapy8. The demand for hand therapy is substantial due to high levels of hand trauma largely caused by interpersonal violence, road accidents9, and work-related injuries10,11. Despite the high demand for hand therapy in the public sector, a majority of therapists with more than 5 years of experience work in the private sector12. Most members of the South African Society of Hand Therapists work in the private sector, and in urban centres13, suggesting limited hand therapy expertise being available to community service occupational therapists working in rural or underserved areas. Research has recommended further investigation into the support and development needs of these therapists for hand therapy, in order to enable sustainable and effective interventions that are responsive to the needs of therapists and the healthcare context5. The purpose of this study was thus to describe community service occupational therapists’ experience of delivering hand-injury care in order to identify their support and development needs. Previous work with this population has also recommended the use of collaborative research approaches that enable these therapists to actively participate in identifying their own needs and articulating strategies to address these5.

To facilitate data generation while supporting co-construction of knowledge between researcher and participants, a virtual community of practice (VCoP) was selected as the medium for data collection. A community of practice (CoP) is ‘a group of people who share a concern or a passion for something they do & learn how to do it better as they interact regularly’ (p. 11)14. A VCoP, or online CoP, is a group that uses the internet to engage with others who share the same interest or concern15 to share experiences and expertise16.

A CoP acts as a ‘container of social learning’ and has three structural components: a domain or specific capability that is important to members; a community or specific composition of group members; and an area of practice that becomes the focus of engagement for members 14. In the present study, hand therapy delivered by generalist occupational therapists was articulated as the CoP domain, and novice community service practitioners, along with the researcher, constituted the community. Delivering better hand therapy was the practice focus of the group. Because community members were geographically dispersed, a VCoP was chosen.

CoP are characterised by sustained learning partnerships between practitioners who commit to interact regularly to collectively and individually improve a specific capability. This commitment to learning together over time is what differentiates CoPs from other more informal social learning spaces14. Evidence of the support and learning needs of generalist occupational therapists5,6,8 suggested that a CoP could act as an effective data collection tool – the researcher gathering data of participants’ support and learning needs, while members accessed support and negotiated learning for improving their hand therapy practice. Data collection would then also offer substantial benefits to participants including journal club sessions, sharing of resources, and support for learning. Community service is a 12-month contract and few therapists continue in the same practice setting on completion of this service period. So while joining the VCoP constituted a decisive commitment to the community, it was constituted to last only until the completion of their service year, rather than involving long-term involvement typical of CoPs. The choice of an online data collection method during proposal development in 2019 proved fortuitous when COVID-19 restrictions challenged in-person research activity during 2020 and 2021.

The VCoP proved to be a dynamic data collection tool and the benefit that participants appeared to draw from the community was substantially greater than anticipated. To understand these benefits, the objective of this article is to report on participants’ experience of the VCoP for supporting delivery of hand therapy services by novice generalist occupational therapists working in rural and underserved areas. The article is situated in a broader study that sought to extrapolate the hand-injury care support and development needs of therapists from an account of their practice experiences.

Methods

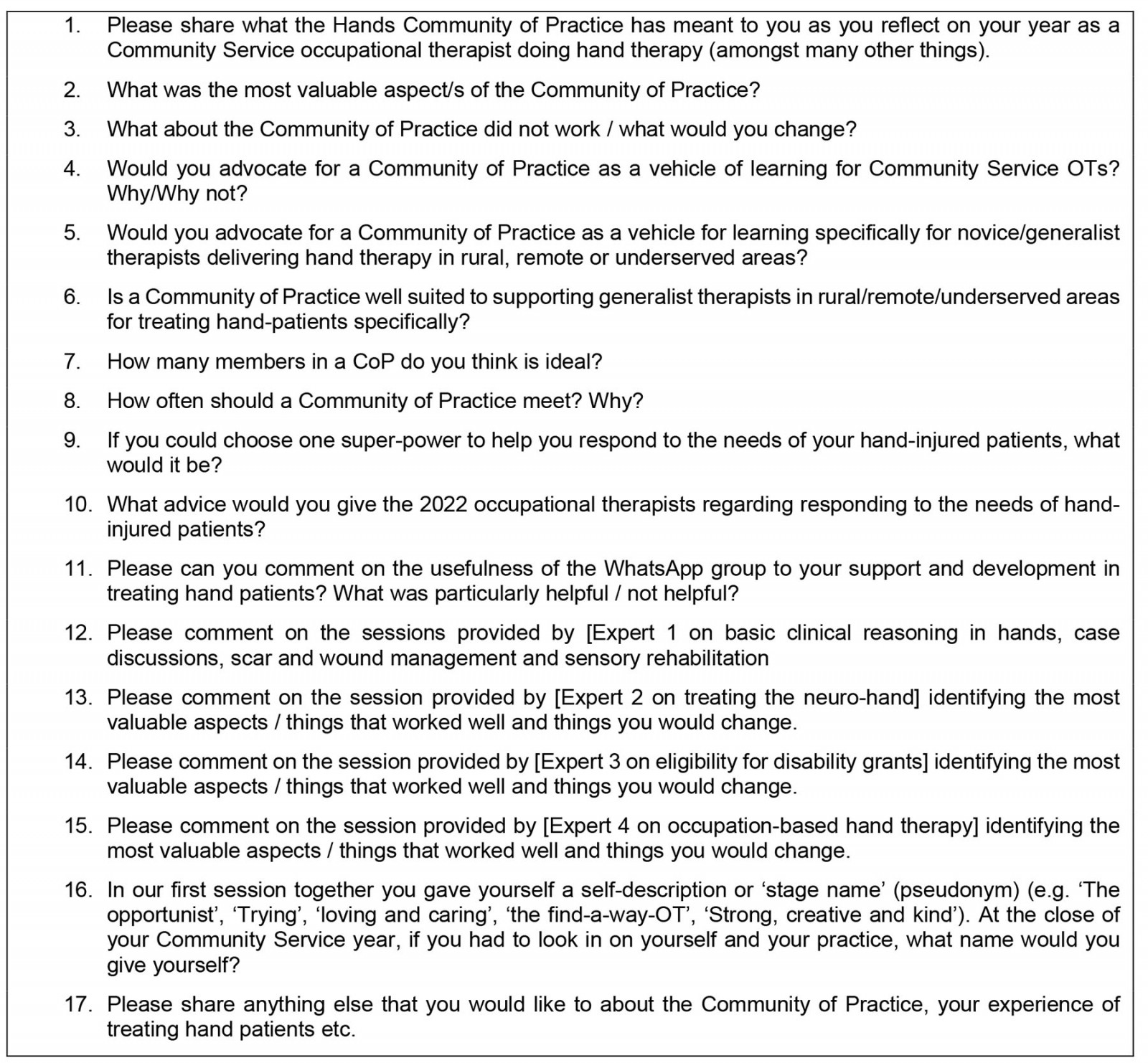

This study employed a qualitative case study design. Invitations to participate in the study were circulated via social media and interested community service occupational therapists attended an online information session about the study in June 2021. Nine therapists provided informed consent to participation and data collection took place from July 2021 to January 2022. Meetings were held on Microsoft Teams every 2 weeks and each meeting lasted around 90 minutes. Data collection techniques used during meetings included photo-elicitation and facilitated reflection activities. Continuous professional development activities were also arranged based on emerging needs in the group and subject experts were invited to present on these topics. These included formal case discussions, a session on clinical reasoning in hand rehabilitation, basic biomechanical and treatment principles, management of the neuro-hand, occupation-based hand therapy, considerations for disability grant eligibility, and sensory re-education. A need emerged early in the study for a platform that could facilitate ‘real-time’ support. Thus additional ethics approval was obtained to include WhatsApp as a data collection platform that enabled participants to troubleshoot clinical challenges, obtaining guidance and feedback from each other and the researcher. Online methods are the preferred method of VCoP evaluation17 so an anonymous online survey questionnaire (Box 1), distributed using Microsoft Forms, was used to capture participants’ experience of participating in the VCoP.

Meetings of the CoP on Microsoft Teams were recorded and transcribed. The WhatsApp chat was downloaded. Data were managed and analysed thematically in NVivo v12 (Lumivero; https://lumivero.com/products/nvivo). The data that evaluated participant experience via online survey were also downloaded as a Microsoft Word document and analysed manually for the specific purpose of this article. Reflexive thematic analysis18,19 was used within the broader study as the type of thematic analysis suited to the researcher’s constructivist paradigm and pragmatic approach to the research question. Analysis commenced in January 2022 with printing of the survey data, reading through this data and making notes. Data were then coded. An additional response was received from a participant in May 2022. A finalised coding list was reapplied to all data in May 2022 after which themes were generated. These themes were presented to participants in an online member-checking interview as well as to the co-authors of the study. Themes were then finalised and a report of the study generated. Demographic data, excerpts from transcriptions, and self-assigned pseudonyms were used to construct simple vignettes for each participant (Box 2) to provide context for their experience of the CoP and to allow the reader to evaluate the transferability of findings.

The trustworthiness of results was strengthened through a number of strategies20. Credibility was established through prolonged engagement and frequent interaction with participants between June 2021 and June 2022. Member checking was used to assess participants’ ability to ‘recognise their experience in the research findings’ (p. 219)20. A report of the study that contained the raw data, coding of data and theme construction was submitted to an experienced research colleague for examination. In addition, the first author engaged in critical reflection during the research process in order to develop insight into her subjectivity and potential biases related to this position. A dense description of participants (presented using vignettes in Box 2) allows the reader to assess the transferability of results. Exposing a record of research procedures and analysis process and logic to an expert colleague strengthened dependability (report submitted for peer audit available on request). The triangulation of data sources (participants) and the researcher’s pursuit of reflexivity undergirded the confirmability of results.

Box 1: Questions included in the online survey to evaluate members’ experiences of virtual communities of practice participation.

Ethics approval

All necessary ethics permissions were obtained prior to data collection through the University of the Witwatersrand Human Research Ethics Committee (Medical) (M200235).

Results

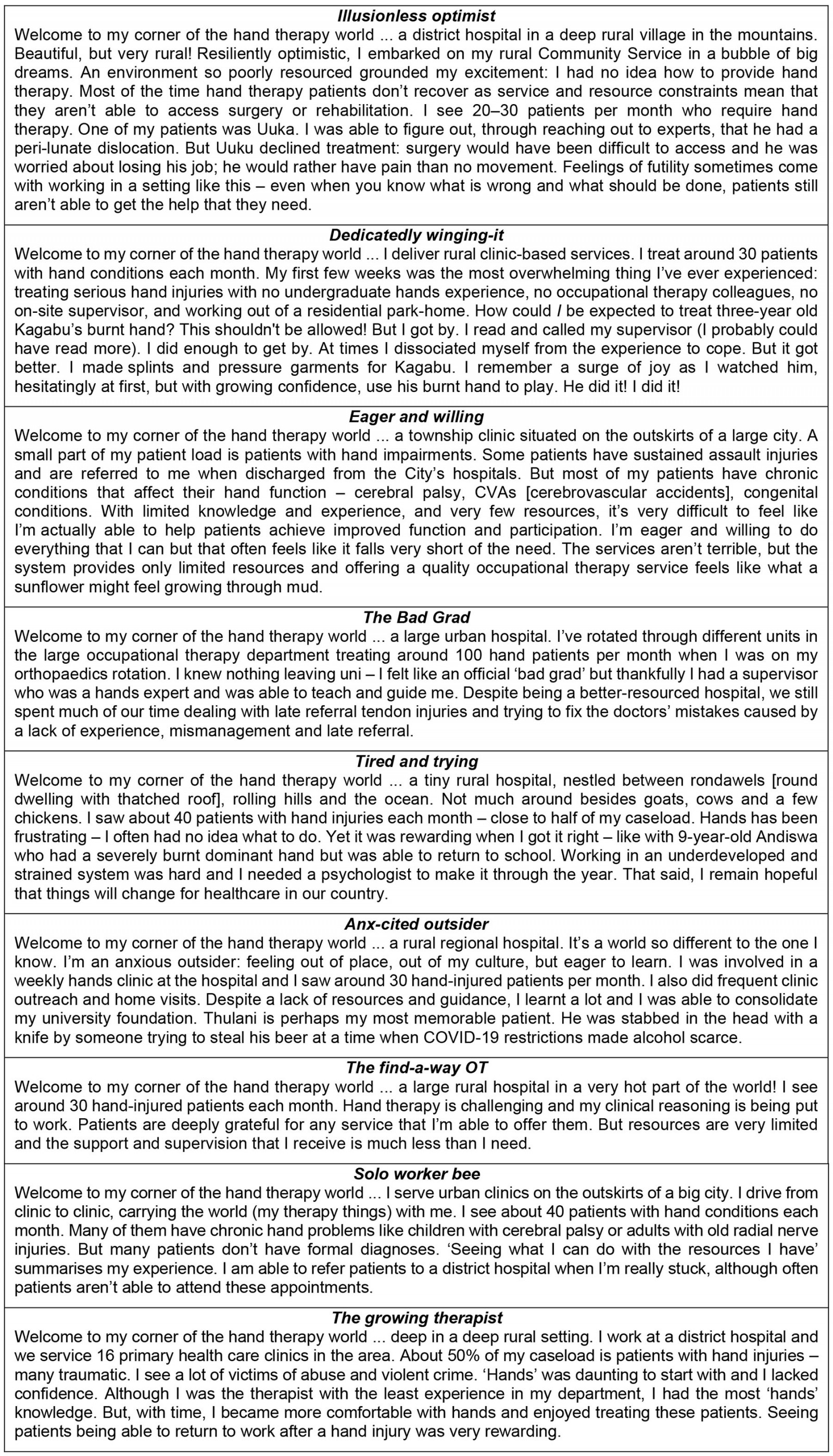

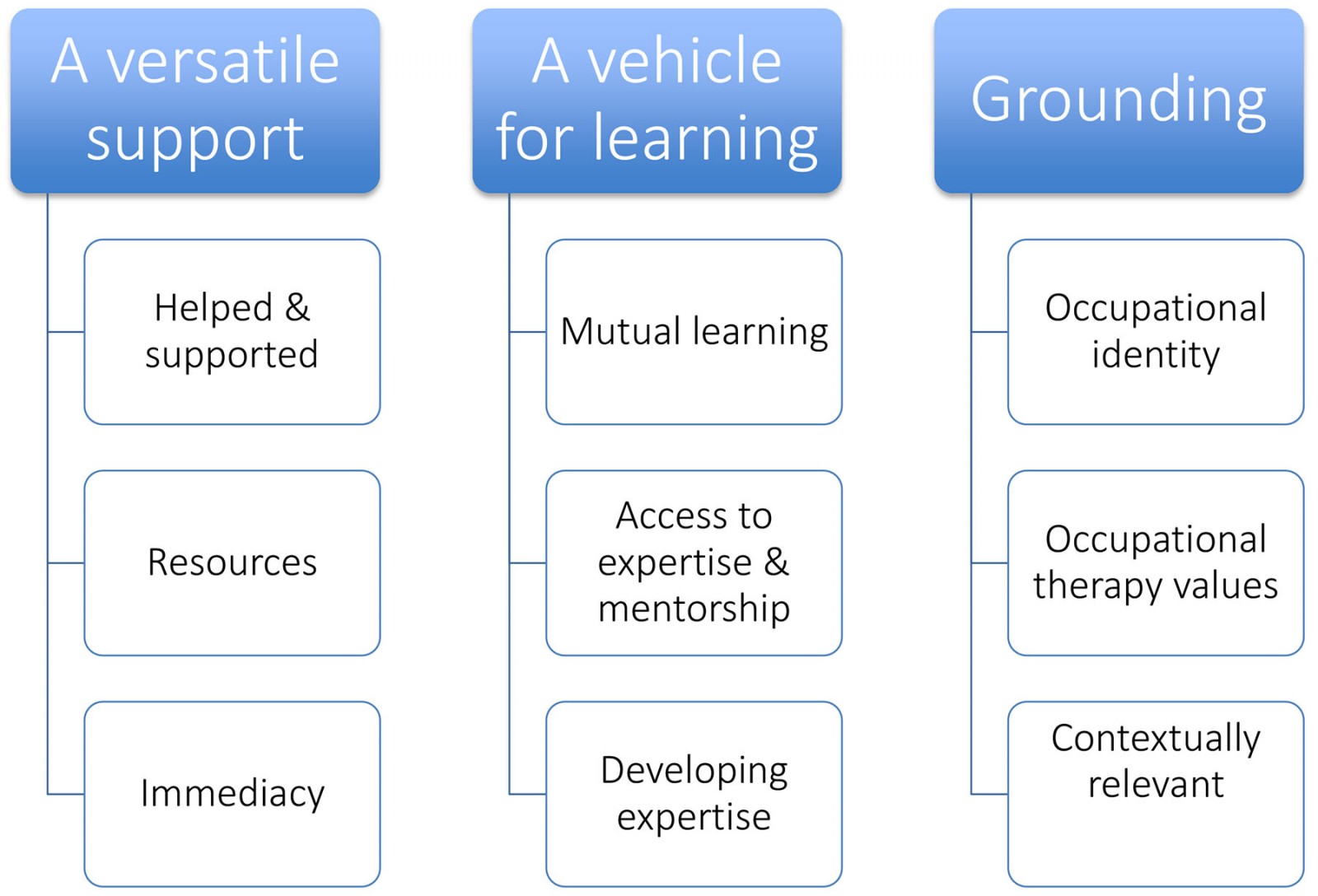

Seven of the nine participants responded to the online CoP evaluation survey, the aim of which was to describe participants’ experience of the benefits of participating in the CoP for supporting their delivery of hand therapy services. A vignette of each participant’s experience is presented in Box 2. This is followed by an illustration (Fig1) and description of the three themes generated from analysis. Recommendations for CoP logistics shared by participants are outlined at the end of the section.

Box 2: Participant (n=9) vignettes: Welcome to my corner of the hand therapy world.

Figure 1: Themes and subthemes that captured participants’ experiences of the benefits of the virtual community of practice.

Figure 1: Themes and subthemes that captured participants’ experiences of the benefits of the virtual community of practice.

Theme 1: A versatile support

The CoP proved to be a space where participants could receive much-needed support for delivering hand-injury care in underserved settings as novice practitioners.

Help and support: Firstly, the CoP facilitated feelings of being helped and supported. One participant explained:

Everyone was so supportive and willing to listen … to share their experiences which makes sharing yours easier, or just being able to relate … which is ‘good for the soul’ and makes you feel less frustrated and alone in all the struggles. Being able to ask the people for help and knowing somehow we'll figure this out when you have a patient in front of you. (Participant 7)

The CoP provided a sense of the community for the loneliness and sense of pressure experienced in a rural setting:

When you're in rural and remote areas you often end up feeling really lonely and there's a lot of pressure. It's not like in the city where if you don't know how to do something you can … send your patient to … see another therapist 10 minutes away. You are the only therapist and it's all on you. So having a community of people who can support you and help you is super helpful. (Participant 2)

One participant echoed the value of a virtual community of others ‘in the same boat’. For another participant, the supportive environment enabled her to share her vulnerability as a novice therapist, referring to the CoP as ‘a safe space to admit my weaknesses’:

It's a great support system to inexperienced OTs [occupational therapists] in need of assistance to being clueless with certain cases, support, and ‘counselling’ … a few listening ears which helps knowing you're not alone. The offloading your emotions was so helpful not only for that but also to hear how others coped … knowing it's not just me … coping with commserve [community service] and knowing ‘I'm not so bad because we're all struggling’. It also gave me hope that it will be alright hearing other people's stories … that support was great, others pulling each other up at different times. (Participant 7)

Immediacy: The CoP, with WhatsApp being added as a platform for interactions, was able to meet the need for immediate guidance and support. One member identified this as the most helpful aspect of the CoP:

The WhatsApp group where [the researcher] would answer questions ‘in real time’ (i.e. while you're sitting with your patient in the session). (Participant 2)

Another participant reiterated the stress-alleviating effect of having access to immediate support:

Having the WhatsApp group a phone away is amazing for your stress levels – knowing you can ask for help and there is always a response. (Participant 7)

Resources: Additionally, the group provided a space to readily share resources:

Having a place to access resources … has assisted me in treating hands clients. (Participant 4)

Group interactions also supported resourcefulness:

... you learn so many tricks from others, [like] how to use old objects as resources. (Participant 7)

Theme 2: A vehicle for learning

Participants shared how the CoP provided a rich opportunity to construct learning.

Mutual learning: Learning was first of all characterised as mutual learning. ‘Sharing’ and ‘comparing’ were words used by participants to discuss this reciprocal learning. One participant reflected:

... it allows you to share your experience and learn from others that are in the same situation. (Participant 6)

Learning through other participants’ clinical questions was another aspect of this mutual learning:

It was helpful to see others’ questions and the answers to them ‘cause often you’d get a similar case and already have knowledge on it because of the group. (Participant 6)

Access to expertise and mentorship: Learning in the CoP was supported by being able to access expertise in the group as well as the group providing a means to mentorship. Two participants explained these benefits:

Being given access to people who could actually help me and teach me how to clinically reason through cases felt like winning the lottery in terms of hand therapy. (Participant 2)

By having a senior OT as part of the CoP also assists with mentorship when that is not available in your Community Service setting (i.e. you are the only therapist). (Participant 6)

Developing expertise: Through the structure provided by the CoP and the interactions that this facilitated, participants were able to develop expertise for hand therapy. This was facilitated by opportunities to reflect in the group and a ‘safe space’ to gain knowledge and skills:

It has been a place to reflect and grow as an OT practitioner in terms of Hand Therapy. It has allowed me a safe space to admit my weaknesses and limitations whilst providing an opportunity to gain knowledge and skills by talking to other OTs in the same situation. (Participant 5)

A similar benefit was explained by a participant in the context of being responsible for a diverse caseload:

... as a generalist OT there are so many conditions you have to focus on ... so there's a one-stop group to give you knowledge so that you don't have to look up all the information by yourself ... information you wouldn't necessarily have found in articles ... (Participant 6)

The learning space provided by the CoP compelled critical thinking, which contributed to the development of expertise:

It also forces you to think on the spot, even if it’s not your patient, which develops your clinical skills for hand therapy. (Participant 6)

The CoP also supported the development of clinical reasoning. One participant explained:

Yes, although each hand is different, familiarizing yourself with other hand injuries will always improve your clinical reasoning! (Participant 3)

Including CoP members with more advanced expertise who can guide clinical reasoning was deemed to be important:

… It is so important to find people who can provide you with accurate clinical reasoning when you are unsure of where to go! (Participant 5)

Theme 3: Grounding

In addition to providing support and facilitating learning, feedback suggested that participating in the CoP was professionally and contextually grounding.

Occupational identity: First, the CoP supported some participants’ professional identity as occupational therapists:

It was also striking how it changed the way I look at hand therapy and the role of OT. It made me realize our role better, and have more interest in it than coming in. It made me want to be an OT! Which is really important realization for a Community Service OT. (Participant 7)

When asked what advice to give future community service occupational therapists for providing hand therapy, retaining this occupational identity was prioritised by one participant:

Sometimes when you start seeing hand patients you get really overwhelmed and you feel like you don't know anything but don't forget what you learned at varsity. You do know the basics. You might have to brush up on some of the technical skills and knowledge but don't let that overshadow what you already know about occupations! Don't be afraid to brainstorm and experiment with your patients in terms of finding new ways of doing things but make sure that you're always focusing on the occupation. Don't lose your identity as an OT while you're trying to improve on your biomechanical knowledge and skills. (Participant 2)

Occupational therapy values: The CoP also served to consolidate occupational therapy values for participants. Participants shared that the CoP was helpful:

- ‘[to] always think back to the patient’s goals’ (Participant 3)

- ‘[for] learning to remain client centred’ (Participant 4)

- ‘… to remember the hand belongs to a person and treat the person holistically’ (Participant 4).

Responsive: The CoP was also contextually grounding in that it responded flexibly to the context-specific and emerging needs of novice practitioners. These included topics they were struggling with, guidance on when to terminate treatment, and how to deliver hand therapy in a community setting. Highlights for participants were:

… Having people come and talk to us about topics we are struggling with. (Participant 2)

It was great that she covered the basics of neuro … first and then gave a lot of tips, which is so helpful coming from a super experienced OT. Her reassurance on when to discharge patients and how to remove yourself from things you really cannot help with meant so much to me especially because we are inexperienced [and] you don't know when to stop trying to help. It worked well that she gave time for us to ask questions because then she could identify what we really struggle with. [The neuro-hand] was also one of the sessions [that] we asked for specifically which I think is important for the hands CoP – identifying [what] the members needs are and then responding to that, as was done. So it's not just another lecture or course but it is specific. (Participant 6)

… to [learn] about hand therapy and how to integrate it into the community setting. (Participant 4)

Recommendations for future virtual communities of practice

When asked if they would recommend a CoP as a vehicle for learning for community service occupational therapists, the affirmative response was unanimous:

Definitely!!! ... You really come in knowing (nothing) ... I felt guilty about how little I knew and how bad my therapy was ... so being in a group with other people who are in the same boat as me was so helpful ... It was such an amazing experience. In writing the handover for the new Community Service occupational therapist coming to our hospital, I’ve been recommending all the courses that I went on this year that I found helpful and it’s a little bit sad that I can’t recommend this one because it definitely was the most helpful and provided the most support. (Participant 2)

Participants also provided some helpful feedback around future VCoP logistics. Participants frequently had difficulty accessing the Microsoft Teams platform and recommended that a more accessible platform (Zoom or WhatsApp) be used for the CoP. They recommended that a CoP have 5–10 members and meet every 1–2 weeks for a formal 60–90-minute meeting.

Discussion

This article describes novice occupational therapists’ experience of the benefits of a VCoP to support hand therapy practice while completing a mandatory service year in rural or underserved clinical settings in South Africa. Three themes were generated from analysis, demonstrating that the VCoP was a versatile support, a vehicle for learning, and both professionally and contextually grounding. Although VCoPs are not the only form or format in which social learning and support can be facilitated, findings found strong agreement with existing literature around the benefits of VCoPs. This, along with the recommendations that participants provided for future VCoPs, is therefore discussed in this section.

A versatile support

A key benefit of the VCoP in this study was the experience of support. This clear finding is less overtly expressed in previous occupational therapy CoP literature. The participant vignettes reference the complex and resource-constrained settings in which participants worked that contributed to their need for support. It is likely that the need for support for many of the participants was linked to their professional isolation, with many of them working as a sole occupational therapist or in a team with limited hand therapy expertise. Isolation, both social and professional, is a common challenge experienced by health professionals, which can be powerfully mitigated by VCoPs21.

Quotes from participant experiences suggest that the need for knowledge and the need for support are closely connected. The expanse of social support literature demonstrates the evolution and complexity of the concept. However, early conceptualisations of types of support identify emotional support (which fosters feelings of comfort), cognitive support (which assists understanding through information, knowledge or advice) and material support (which contributes practical goods or services to help solve problems)22. Delineating these aspects of support highlights the overlap between the learning needs and support needs of participants, suggesting that the tacit need for support is facilitated during the learning process. The literature also identifies the significance of the timing of support, which was a very important factor for participants in this study, who often required immediate support22. It is timely access to knowledge and expertise that sets VCoPs apart from other models of knowledge delivery23.

A vehicle for learning

Learning is central to the purpose of CoPs and thus it is not surprising that learning was integral to participants’ experience. Contemporary CoP theory, as well as seminal social learning theory proposed by Vygotsky, highlight the importance of communities to effective learning24,25. There is growing evidence within the occupational therapy literature supporting the use of CoPs for learning, with a 2017 literature review reporting emerging use of CoPs within occupational therapy26. In the available articles (n=5), there was evidence that CoP’s facilitated knowledge sharing, knowledge translation, learning through boundary crossing, and reflection. This early evidence highlighted the potential of CoPs for the continuous professional development of occupational therapists26. More recent work with occupational therapists working in an acute paediatric setting in Brazil has added weight to this recommendation: participation of nine occupational therapists in a CoP demonstrated how it utilised dialogue and collaborative reflection for knowledge development and generated practical knowledge for acute paediatric practice within the group27. The latter findings also echo the subthemes in this study that speak to a CoP being a means to accessing resources and for providing opportunities to apply knowledge to one’s own practice context.

The shared or mutual nature constituted a clear feature of participants’ knowledge acquisition in this study. This co-learning process is indeed a hallmark of CoPs21, and engaging in ‘thinking together’ is argued to be at the heart of COPs28. Participants in this study highly valued being able to engage with colleagues with hand therapy expertise. Barry and colleagues’ review of CoPs for facilitating occupational therapists’ continuous professional development did not overtly mention the importance of having experts or specialists within the group but rather highlighted the value of diversity in perspectives in the group26. Similarly, explicit inclusion of ‘experts or specialists’ within the group is not highlighted by CoP theorists29, perhaps because the theoretical positioning of CoPs privileges the expertise of all and the co-construction of knowledge and meaning.

Grounding

The affirming impact of the CoP on occupational therapy values and identity reported in the third theme of the current study was an unanticipated finding for the first author, who had engaged with participants for a prolonged period. Although unexpected, this finding should not be surprising. Communities of practice are considered a platform for the social theory of learning24 in which learning constitutes an individual’s social formation, and thus results in identity change28. Wenger-Trayner explains the link between learning and identity formation: CoP theory views learning and the ‘becoming of the learner’ (p. 145) as aspects of the same process25. Instead of the acquisition of knowledge and skills alone, the theory places the negotiation of meaning at the centre of learning. Because negotiating meaning involves ‘becoming a certain person in a certain social context’ (p. 145), identity formation becomes part of learning25. Occupational therapists’ professional identity continues to be an issue raised in international30 and South African31 literature and so this finding is a particularly important one. Turner and Knight’s review of occupational therapists’ professional identity presents reasons for and consequences of the profession’s struggle with identity. The authors identify a poor grounding in the paradigm of occupation as being largely responsible for occupational therapy’s difficulty in establishing its identity. Interestingly these researchers identify CoPs as the vehicle through which occupation-based practice, and the profession’s identity, can be reinforced32. Findings from the study of the aforementioned Brazilian paediatric occupational therapists CoP validate this conclusion. They found the CoP not only produced professional practice knowledge through dialogue and reflection, but also provided a sense of belonging and affirmed participants’ professional identity33.

Evidence for the use of CoPs and VCoPs in occupational therapy is slowly increasing while research around their use within other health settings is substantial23. Project ECHO is one example of a VCoP model used to improve healthcare outcomes, initially designed to address service disparities in rural and remote areas34. The model seeks to make expert knowledge accessible ‘at the right place, at the right time’. ECHO participants join a VCoP in which the group shares guidance, feedback, and support. During ECHO sessions, group members present clinical cases to one another (including a specialist within the group) for discussion. A non-hierarchical ‘all teach, all learn’ philosophy facilitates reciprocal learning where best practice is applied to participants’ local contexts34.

Innovation: an unexpected by-product

Innovation is also a common by-product of the knowledge construction that happens in CoPs17. Innovation was not reflected in the data analysed for this study but the group developed a practice innovation shortly after data collection was completed. During the course of the study, participants had identified the need for appropriate hand therapy resources and equipment that was portable and could be used for assessment and treatment of a diverse caseload. In early 2022, shortly after the completion of the study, participants and the first author developed a practice innovation, Hand Therapy On The Move (HT-OTM). HT-OTM is a fully equipped hand therapy station that can be carried as a backpack or pulled on wheels. The innovation was piloted in two rural locations in South Africa and has been received with great interest at both local and international conferences35. Opportunity for enabling access to the therapy resource through public health tender processes in South Africa, and sharing the innovation with international colleagues for replication in their settings, is being explored. This is an example of simple ways that CoPs can contribute to progress in a field of practice17.

Recommendations for future use of VCoPs

It is recommended participant feedback be used to refine the VCoP model used in this study, and upscale it for implementation amongst rehabilitation personnel in South Africa. Participants provided recommendations around the optimal VCoP size, the frequency and duration of scheduled meetings, and preferred electronic platforms. It is necessary to make overt that the success of VCoPs is dependent on basic resources: protected time to participate, electricity and adequate internet bandwidth23, and an electronic device for each member. Participants in this study, particularly those in more rural settings, sometimes experienced connectivity difficulties that affected their participation in meetings. Scheduled load-shedding, and unforeseen changes to these schedules in South Africa, means that participant access to online platforms can easily be disrupted. VCoP members will need to factor these variables into group planning and logistics to mitigate the impact of these disruptions.

A strong sense of participant satisfaction with the VCoP in this study motivated the separate analysis of the evaluation survey, as well as this article. Key components of the VCoP that contributed to expressed satisfaction were access to real-time support facilitated by use of WhatsApp, access to expertise in the group, and the flexible format that allowed learning to address emerging needs in the group. Satisfaction with the VCoP was largely a supplementary finding in this study but is a construct that should be overtly considered in VCoP design. There are higher levels of user satisfaction when the collaborative learning enables participants to learn about patient diagnosis and treatment, when participants develop trusted networks, and when the mutual learning process strengthens members’ ‘share capital’21. The perceived effectiveness, efficiency and knowledge acquisition that a virtual platform enables have also been identified as variables significantly associated with member satisfaction that should be considered in VCoP planning and implementation21.

Closely linked to the importance of user satisfaction is the importance of evaluating the outcomes of CoPs. This study evaluated participants’ experience of a VCoP while delivering hand therapy as a novice generalist practitioner, which was suited to the study purpose and aims. What was not considered, however, was the impact that the VCoP had on the hand therapy services that participants delivered. This may be considered a limitation but represents an important opportunity for future research.

A lack of rigour in published methods of evaluating the impact of CoPs on public health practice23 was reported in a 2017 systematic review. The review of the evidence concluded that CoPs that facilitate reflective practice, diverse networking and structured problem-solving may provide effective support for public health professionals. However, further work was recommended to establish rigorous methods to evaluate the impact of CoPs on the health of populations23. A recent publication36 demonstrates how this gap can be addressed: ECHO Ontario Mental Health programme has proposed an implementation framework for VCoPs, which combines Proctor’s implementation outcomes37 with ECHO project expertise. The framework considers eight implementation outcomes, along with respective success thresholds, for the evaluation of acceptability, adoption, appropriateness, cost, feasibility, fidelity, penetration, and sustainability36.

Strengths and limitations

A number of strengths and limitations to this study are acknowledged. To our knowledge, this is the first South African study to report on the use of VCoPs for strengthening the capacity of rehabilitation personnel. The questionnaires included in the evaluation were developed towards the end of the broader study’s data collection period and were informed by the researcher’s active participation with VCoP members. They were also partly focused on the main research purpose rather than specifically targeting an evaluation of the CoP and its benefits. This may have contributed to assumptions that limited the objectivity of questions. However, from the researcher’s constructivist perspective and the reflexive thematic analysis approach taken, responsively developing questions based on prolonged engagement with participants may also be considered a potential strength.

While considering both perspectives, future CoP evaluation strategies should be evidence-informed and broadly planned prior to the commencement of the group. In addition, the questionnaire did not undergo review by experts, which would have strengthened its content validity and should be ensured in future research. Finally, two participants chose not to participate in the evaluation. It is possible that these participants’ experiences of the group were less positive, reducing the range of experiences included in the data. Building opportunities to complete evaluations into scheduled group sessions may mitigate this challenge in the future. It is also acknowledged that gathering data through open-ended survey questions potentially restricted the depth of qualitative data captured in this study.

Conclusion

‘To achieve healthy lives and wellbeing for all, the right knowledge must get to the right place at the right time for those who need it most’ (p. 634)23. Results from this study contribute to a growing body of evidence supporting the use of VCoPs to achieve this imperative. This study also demonstrates how a VCoP can simultaneously be used as a collaborative data collection tool while addressing the needs of participants for support, learning and grounding within their professional identities and practice contexts. As demonstrated in this study, CoPs can also act as hubs for contextually responsive innovation. Upscaling the implementation of VCoPs to support the practice of rehabilitation personnel working in rural and underserved contexts is recommended as they extend access to services to populations that need it the most.

Acknowledgements

Sincere gratitude is extended to the nine occupational therapists who participated in the research and for their contribution to knowledge of the support and development needs of novice occupational therapists in South Africa.

Funding

Kirsty van Stormbroek was supported by the Consortium for Advanced Research Training in Africa (CARTA). CARTA is jointly led by the African Population and Health Research Center and the University of the Witwatersrand and funded by the Carnegie Corporation of New York (Grant No. G-19-57145), Sida (Grant No:54100113), Uppsala Monitoring Center, Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation (Norad), and by the Wellcome Trust (reference no. 107768/Z/15/Z) and the UK Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office, with support from the Developing Excellence in Leadership, Training and Science in Africa (DELTAS Africa) program. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the Fellow.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

You might also be interested in:

2008 - Clinical placement and rurality of career commencement: a pilot study

2008 - Health behaviors and weight status among urban and rural children