Introduction

Rural people across most nations, regardless of relative national wealth and development, live shorter lives, on lower incomes, with less formal education, and experience greater poverty, illness, and injury than their urban-dwelling peers1-3. This rural–urban health disparity persists across countries and compounds other social determinants of health such as race and gender2 and has been highlighted for decades by WHO3,4. Multiple causes have been suggested including higher risk factors such as farming, poorer general and health literacy2, distance from infrastructure5,6, limited public transport, internet, health service resourcing, and shortages1-6. All these factors, at their most fundamental, are features of geography. Human biology remains relatively constant, while geography significantly impacts bodily experiences and health outcomes1-3. In rural and remote health, there appears a dominant assumption that increased inconvenience and cost for accessing health care are features of rural geography that should be expected by rural people6-8. This critical narrative review aims to challenge this assumption by applying concepts from critical geography to suggest rural geography has been shaped to result in exactly the health outcomes experienced by rural people, and that focusing policy on reshaping rural geography9 may result in better health services and outcomes.

The inconvenience and cost experienced by health service providers using predominantly urban-developed models to provide health care to rural and remote communities are often framed, particularly in western literature, as challenges posed by the places themselves6,8. Rural and remote places are described as being too far, too sparse, and too challenging6,8. For example, the Australian Government Institute of Health and Welfare states rural people ‘face unique challenges due to their geographic location’10, implying this issue is location, not service design. Rural health literature also frequently suggests rural geography is to blame by focusing strategies to increase ‘access’ to predominantly city-based health services for rural people11. For example, a review of cervical cancer screening accessibility separates health system barriers (eg communication strategies) from contextual barriers (eg distance to treatment centres)12, yet the location of screening centres is not a natural feature of geography; it a human decision. Even when limited rural infrastructure is acknowledged, the lack of transportation is often cited as a contributing factor to poor rural outcomes11,13. For example, ‘lack of transportation can lead to delays in treatment, inappropriate medical treatment, and unmet healthcare needs’ (p. e620)13. However, transportation routes are also human decisions.

Rural geography as a cause of disparity is also noted in phrases such as, ‘Many rural places struggle to attract and maintain an adequate health workforce’ (p. 62)14, suggesting it is the place’s failure to attract workforce. Consequently, many rural workforce projects focus on strategies to convince urban-based health workers to relocate to rural places by incentivising, increasing attractiveness, or trying to convert potential recruits to rural life3,15-17. However, developing sufficient geographical attractiveness may be out of the control of some rural or remote places, whose decision-makers may not be able, or desire, to become attractive to urban people18. For example, Australian regional places with natural assets such as national parks and beaches within commuting distance of significant infrastructure are more likely to attract population growth18. But decisions about how natural assets are managed (eg locations of open-cut mines or national parks) and where infrastructure (eg hospitals and highways) are built are often made by governments based in cities despite preferences of local rural people18. With these points in mind, it is argued that the social processes influencing rural geography are often what is missing from discussions about rural health19.

What lessons can health decision-makers and policymakers take from a more critical understanding of geography that goes beyond the tyranny of distance as the reason for poor health outcomes for rural people? Geography is a diverse field that examines physical environment, infrastructure, demographics, population distribution and, in the field of critical geography, the influence of politics, ideology, and economics on the way people behave in places9,19,20. Critical geographers argue that spaces are not empty containers into which social life is poured; rather, these are created by social processes are reproduced to meet contemporary social ideologies9,19,21. Geography is seen to both shape human behaviour and be shaped by human behaviour9,19,20. For example, humans build infrastructure such as highways, airports, and railways to bring us closer together in a relative sense19. We designate space and build infrastructure for particular activities such as sport, shopping, mining, and housing19. Naturally occurring geographical features such as water sources, ore deposits, and climatic conditions may influence initial decisions about space utilisation, but humans then shape geography to support human activities19.

This critical narrative review argues that: (1) if it is humans who shape geography, it therefore follows that geography is not separate from the social world, but is deeply socially integrated19; (2) if society has shaped geography to be as it is, geography cannot be cited as a natural reason for rural health disparities; and (3) as a result of acknowledging the social shaping of geography, we have the potential to reshape geography to improve rural health outcomes. To do the work of reshaping geography to improve rural health outcomes, this review identifies the potential value of the geographical concept of spatial justice as a lens through which the reshaping of policies and decisions9 to address rural health disparities can occur.

Approach

In this critical narrative review, we examine the concept of reshaping geography to improve rural health outcomes, by drawing upon concepts from critical geography and applying them to Australian examples. We approach the review from the perspective of spatial justice, a concept synthesised and conceptualised by geographer Soja9. Soja drew on decades of literature to conceptualise the term as describing the impact of geographic location on a person’s experience of justice. We also draw on the work of philosopher and geographer Lefebvre, who is a seminal voice in highlighting how space is shaped by social processes and proposed a tripartite model of the shaping of space19, and particularly considered the impact of social processes on rural spaces22. We are also influenced by the work of Harvey21, a seminal voice in the field of uneven geographical development, or the concept that resources are more available in some spaces than others due to social ideologies. We aim to highlight how health service design and policy could be modified to increase spatial justice for rural and remote communities.

Ethics approval

This critical narrative review approach was granted ethics exemption by the Western Sydney University Ethics committee due to negligible risk from using existing non-identifiable, publicly available data (reference EX2023-01).

Spatial justice

Critical geographers explain that decisions about which spaces are used, who can use them and how, are influenced by social norms19,21. Spatial justice literature suggests powerful groups construct and maintain places to perpetuate existing power and redistribute wealth from one space to another9,21. So, as Soja explains9, central urban spaces are often better resourced and reserved for people with wealth and power, with less powerful people pushed to peripheral places. Exclusion can be overt, such as in gated communities, land taxation rates, and police/security measures such as ‘no loitering’ rules, which privilege those who can afford often-expensive city-centre real estate. Subtle exclusion also occurs, such as in toll roads, parking fees, and limited public transport options, which privilege those with sufficient funds to purchase a car or city-based property. These socially constructed geographies mean where a person lives significantly impacts the opportunities available to them. Spatial justice applies Rawls’ well-known concept of justice: that socially constructed disparities in opportunity are unjust23, and therefore disparate opportunity as a result of location is also unjust9,24.

Social justice approaches to health care are not new, and the social dimensions of health are commonly cited as influencing the health outcomes experienced by individuals and populations25. However, health care traditionally focuses on personal and temporal, rather than spatial, dimensions with spatiality seen as a more fixed and unchangeable factor of ‘environment’24. For critical geographers, justice is inherently place-based, as fairness can only ever be relative to context; resources required in one space may be unnecessary in others9,19,21,24. Spatial justice occurs not when resources are equal; rather, when opportunities – in this case opportunities to be healthy – are equal regardless of location9.

Social shaping of geography

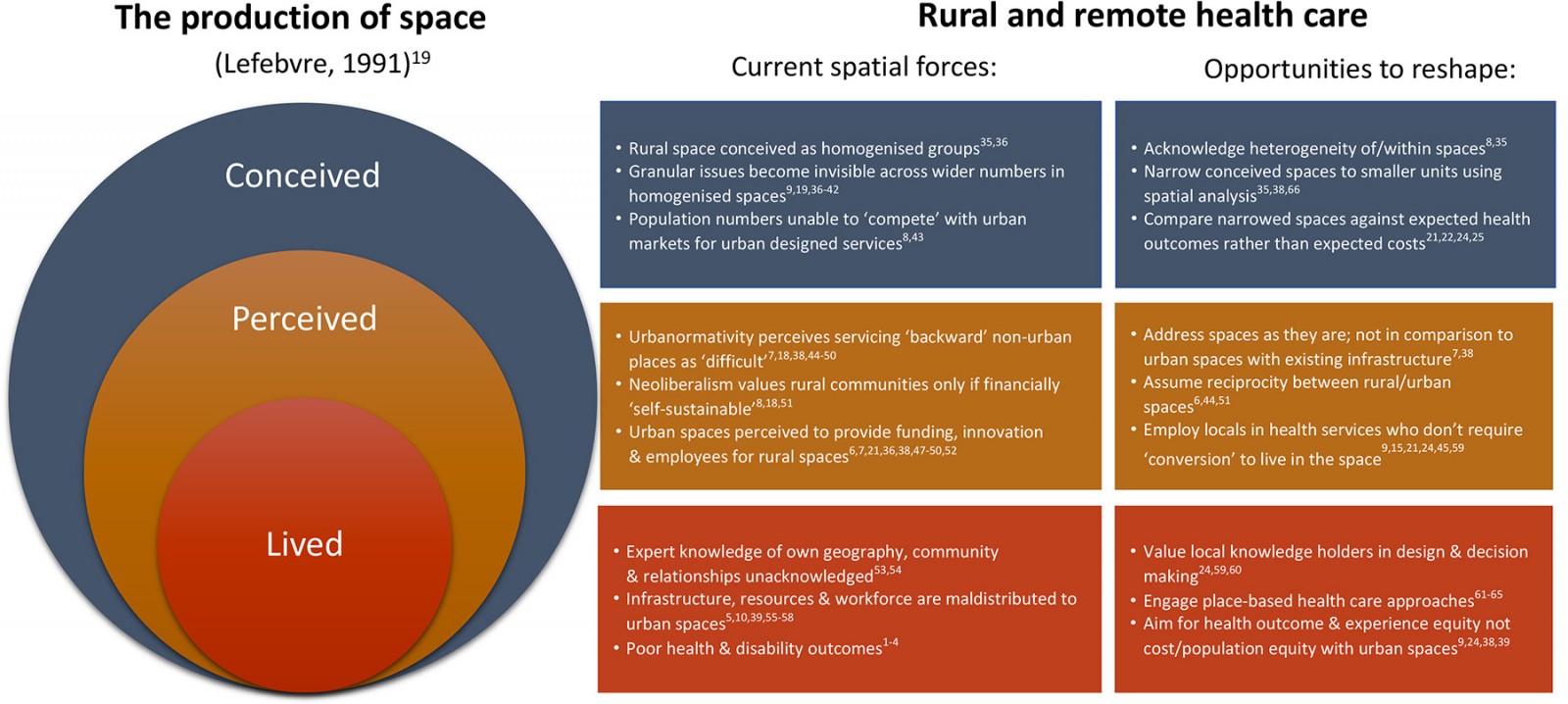

Lefebvre’s discussion of social production of space19 underpins much of the spatial justice literature9. Lefebvre’s tripartite approach suggests space is produced in three ways: conceived, perceived, and lived. Lefebvre explains places are conceived to exist by society using demarcations, boundaries, and definitions (eg that Australia as a country is a socially developed concept). Demarcations are signalled with fences, passports, and borders announcing who can/cannot access certain spaces. Spaces are also perceived from and by people within and/or external to them as incorporating social meaning. This can include symbolism, fantasy, and imagined understanding of a space (eg the perception that Australia is ‘down under’ and full of blond surfers). Finally, lived space encompasses lived experiences of people within a space, and the making of personal histories is within and shaped by the space. Lefebvre suggests that lived space is the only real experience of space but is difficult to explain or quantify as it is unique to the person–place interaction. Considering the multifaceted ways that the conceived, perceived, and lived experiences of spaces as outlined by Lefebvre provides a useful way to understand spaces, the ways that they are produced, and the resulting experience of those who inhabit them. Consequently, we have used these three key concepts of Lefebvre’s to structure our case for spatial justice as a lens through which rural and remote health care can be viewed and, in doing so, provide insights into the reshaping of rural and remote geography to identify opportunities to improve rural and remote health outcomes (Fig1).

Modern ideologies influencing the shaping of geography

Social scientist Harvey21 expands on Lefebvre’s concepts to integrate concepts of justice as core considerations of human shaping of geography. Particularly, Harvey outlines the impact of global capitalism and neoliberalism ideologies on the production of space over the past five decades. Capitalism, to Harvey26, has been for over a century, and continues to be, the dominant economic system influencing access to goods and services, which are the basis for human life. Capitalism is based on supply and demand setting the prices for goods and labour. Harvey argues that capitalism promotes accumulation of capital (wealth) for an elite few and risks exploitation of the many, and therefore requires regulation by the state to achieve even and fair economic development. He suggests that the rise of Milton Friedman neoliberalist ideology promoting instead that the market could regulate itself has resulted in uneven geographic development. Harvey suggests the dominance of neoliberalism in the western world redistributes resources from workers and developing countries to elite financial business and private property owners. These concepts are particularly relevant to shaping of rural geography, as much of the redistribution of resources flows from poorer and commonly rural spaces, to wealthy and typically urban spaces. For example, extraction of mineral resources from rural spaces typically enriches wealthy, western, urban-based mining company shareholders, and fly-in fly-out workers, who work rurally but spend their money in cities27. Given the dominance of capitalist and neoliberal ideologies on modern life, applying Harvey’s concepts to a critical narrative review regarding the shaping of rural geography was anticipated to provide significant insight into the most contemporary shaping of rural health care.

Shaping of rural spaces

Spatial justice literature has traditionally focused on urban spaces, but increasingly the experience of justice in rural places is being explored28. Soja suggests that ‘things do not just happen in cities, they happen to a significant extent because of cities’ (p. 97)9. Critical geographers suggest capitalist and neoliberal ideologies promote global urbanisation, because cities are spaces in which capitalism flourishes9,21. As people increasingly move toward urban ways of living29 geographies of rural and remote spaces have changed21. For example, capitalism aims for maximum profit for minimum costs, which means significant infrastructure, such as banks in small communities, are considered too expensive relative to income generated30. This means as rural communities decrease in population, bank branches close and consumers are encouraged to use the internet29. However, rural people often have poor access to internet services31,32. They cannot use physical banking services as the infrastructure is gone, but neither can they use new banking services as there is insufficient internet access to do so33. Local businesses may then leave as banking becomes more difficult, reducing local employment, in turn reducing the viability of small businesses such as tradespeople, who relocate to larger centres with their families33. This population loss decreases school enrolments, making local schools unviable, leading to further reduction in population34. Thus, capitalist and neoliberal social processes change rural geographies to smaller populations, abandoned infrastructure, and fewer opportunities.

As the example demonstrates, spatial injustice results from multiple independent decisions by multiple people/groups, rather than by intentional design9. However, spatial advantage and disadvantage tend to self-replicate, such that injustice experienced in certain spaces, and comparative opulence in others, becomes normalised and unquestioned9,21. Examining the shaping of rural geographies through Lefebvre’s three spaces19 helps to highlight how rural spatial injustice occurs, and potential strategies to reshape both rural geographies and health care to achieve more just opportunities (Fig1).

Figure 1: Applying Lefebvre’s concepts of space demonstrates some of the factors shaping rural and remote geography in Australia, and identifies opportunities to reshape space to promote justice1-10,15,18-22,24,25,35-66.

Figure 1: Applying Lefebvre’s concepts of space demonstrates some of the factors shaping rural and remote geography in Australia, and identifies opportunities to reshape space to promote justice1-10,15,18-22,24,25,35-66.

Current shaping of conceived rural and remote space

Conception of rural and remote places in healthcare mapping can be problematic for spatial justice. Traditionally, area-units of measurement are not standardised by total area, but by population numbers, resulting in very large area-units of rural areas with low population density and very small urban area-units with high population density35. Rural area-units may cover highly disparate geography including multiple towns, villages, farmland, and wilderness, while highly populated urban area-units may cover just one city block35. Often these spaces are further homogenised into broad standardised categories, such as urban, rural, and remote, which limit detailed understanding36. Neoliberal ideologies prefer broad standardisation to allow abstract and nuance-free comparison of market success19,37. Working in the abstract anonymises people to numbers relative to productivity goals19,37. That is, closing a rural hospital based on cost comparisons with urban spaces is emotionally and morally easier if one can ignore the impacted people and their lived experiences.

Further, standardising and homogenising conceived spaces into large conglomerates expands the problem space to the degree that problems are hidden or addressing the issue becomes impossible36,38. Issues that are significant in one regional, rural, or remote space may not be in another36,38. Homogenising non-urban spaces ignores significant place-based differences influencing health outcomes and it limits what can be done to change the lived context9,23,38,39. For example, despite the World Bank Group reporting 100% of Australians have access to clean water40, some small, remote Western Australian communities can access only water contaminated with uranium, salt, and nitrates at levels known to be nephrotoxic41,42. The cost of remediating or building infrastructure to provide alternative water supply to these small communities was deemed too high given small population numbers, so instead governments exempted water suppliers from meeting water safety standards in these communities41,42. This suggests cost benefits were calculated over state population numbers, which supported sacrificing the small percentage of people in these communities, without impacting the overall percentage of Australians with access to clean water. However, access to clean water is a key issue impacting 100% of people living in that space. Applying a spatial justice approach would require redistribution of state resources to provide basic clean water supplies to ensure equal opportunity for health, regardless of location.

With the fundamental assumption of capitalism resting on competitive markets, rural spaces, in which capital and people are already limited, are unlikely to ever ‘win’ competitions with urban spaces8. For example, a piece by van den Berg et al lauded using economic modelling to demonstrate the perceived economic value of closing three regional paediatric and maternity wards, stating it reduced accessibility for only 8% of the population43. This example demonstrates the fundamental flaw in population-based modelling for health services. Those 8% are still people, and this decision impacted 100% of the people in those spaces. This seeming appeal to utilitarianism – the greatest good for the greatest number67 – if applied at a high enough level, can always justify denying spaces with low population numbers infrastructure, resources, and services8.

Addressing conceived rural and remote space to support spatial justice

Applying spatial analysis processes to smaller area-units may provide the nuance required to support key health issues in conceived spaces. Spatial analysis uses statistical and geographical methods to correlate locational (x,y) points or areas (eg local government areas, postcodes) with other data, such as health and wellness data and distance from infrastructure, within that space66. It aims to identify patterns related to geography rather than within the data itself66. Spatial analysis is becoming increasingly sophisticated in methods, tools, and datasets to analyse and display health and social data across space66.

Narrowing the conception of rural and remote spaces to smaller area-units based on uniform areas rather than population is likely to highlight spatial differences in opportunity and spatial nuances in policy and legislation35. The UN recently endorsed a standardised measure considering population size over standardised units of space to distinguish rural from urban35. In this classification, spaces are defined across grid squares of 1 km2, after which population density is examined within the square and adjacent squares. Urban spaces appear as multiple high-density squares, towns as several medium-density squares, while rural areas are represented by many low-density squares. The advantage of a uniform 1 km2 grid is the reduced bias possible from differing size and shapes of units such as local government areas. For rural and remote health, narrowing conceived space to smaller units, such as those proposed by the UN35, could provide greater understanding of relative health indicators, opportunities and more effective application of spatial analysis to achieve spatial justice.

Current shaping of perceived rural and remote space

Perceptions of rural and remote spaces may also contribute to spatial injustice. A significant body of research relates to the spatial stigmatisation of rural and remote places38. Spatial stigmatisation relates to negative and stereotypical perceptions of a place and the people who live there, which significantly disempowers the group, allowing for marginalisation38. For example, stigmatisation of rural and remote places as backward and boring allows these places to be marginalised during debates and decision making about allocation of resources as less important, and therefore deserving of less38. Stigmatisation of rural and remote communities as places of poverty and decline also reduce health professionals’ interest in choosing to work in these spaces7.

Feeding into the stigmatisation of rural and remote places, the increasing dominance of neoliberal ideology promotes values of individualism, independence, and self-sustainability over interdependence and collective ways of living8,18,51. This neoliberal ideology ignores that urban and rural places relate collectively with reciprocity: urban populations rely on rural communities to supply essential primary resources such as food, minerals, and fuel, while rural people and places rely on income from cities51. In Australia, this reciprocity was previously recognised, and rural services were subsidised by urban taxation, under reciprocal expectations to support people who forwent urban conveniences to provide necessary services51. However, neoliberalist ideology increasingly expects rural and remote communities to be self-sustaining to have the right to exist8,18.

‘Urbanormativity’18,44, ‘metrocentricity’ or ‘metronormativity’45 is the perception of rural places as backward and reliant on self-sufficient urban places to provide resources, ideas, and even workforce7,46. Perceptions of rural and remote space are often relative; that is, comparisons are drawn between rural and urban spaces7,36; however, rural–urban relational comparisons are significantly influenced by urbanormativity, resulting in rural places being seen as wanting47. There has been significant scholarship exploring urbanormativity, and it has been observed across most sectors, including but not limited to popular media47, higher education48, music49, disability services50, medical practice and education7, and occupational therapy6. Rural places are commonly perceived in deficit – as backward, less cultured, less interesting, less educated, and in need of saving by urban places – due to their inability to manage their own affairs6,7,47-50.

Urbanormativity appears in health literature as difficulties presented by situational realities of rural geographies such as small populations spaced at great distances apart6,7. Relational comparisons with assumed urban norms of large populations, clustered closely together, allow geographical facts to be framed as ‘difficult’ by policymakers, service providers, and funders to both promote and justify expectations of compromise by rural and remote people6,7,38. For example, when asked about the closure of 150 remote First Nations communities, and relocation of their residents, in 2015, then Australian Prime Minister Tony Abbott stated, ‘What we can’t do is endlessly subsidise lifestyle choices if those lifestyle choices are not conducive to the kind of full participation in Australian society that everyone should have’52.

Framing of many programs to improve healthcare access for rural and remote people have an undertone of inconvenience for normalised urban places, people, and services6,7,38. This framing risks reliance on benevolence from urban institutions to share services to non-urban places, and risks assumptions from service providers and people served that they must be content rather than expect equity of opportunity6. Attempts to solve a so-called rural health workforce ‘problem’ are also often paradoxical. Solutions to these problems commonly call for urban health workers to relocate to rural areas, while simultaneously positioning non-urban practice as less valued and desirable6,7. These perceptions of rural and remote places from an urbanormative lens appear to justify policymakers in shaping rural and remote geography by not acting at all, or removing infrastructure and services. As reciprocity from urban areas to support non-urban areas decreases in social popularity, political decisions have trapped and will continue to trap rural communities between the need to survive independently and expectations that they meet global needs21.

Addressing perceived rural and remote space to support spatial justice

Achieving spatial justice requires reshaping perceived space, particularly regarding rural stigma and urbanormativity, which both act to reduce the value afforded rural and remote places7,33. Adjusting conceived space as already outlined may contribute to perceived space changes by reducing homogenisation to allow comparison of like with like35. However, adjusting how rural spaces are discussed in the media, by decision-makers and politicians to assuming reciprocity is also necessary44. Reciprocity requires challenging neoliberal ideals of absolute individualism and accepting some level of rural–urban interdependence44. We suggest integrating the concept of spatial justice into the rural health policy lexicon to support this change and provide useful language for advocacy. For health care, reciprocity requires shifting expectations of ease and convenience for service providers in applying existing urban models6 to addressing spaces as they are, rather than as they may be wished to be, or that are familiar to urban people.

Rural and remote people typically do not require conversion to valuing or understanding rural and remote places59. They are already living in and often aware of effective ways to support their own communities59. However, locals are often excluded from accessing pathways to support their own communities. For example, developing a rural pipeline of health workers from rural and remote places for rural and remote places is known to be an effective way to build a sustainable rural and remote workforce15. However, accessing the required health professional education often requires relocation to cities, resulting in rural places becoming ‘net exporters’ of health personnel to urban places (p. 144)45. Spatial justice would suggest that, rather than attempting to convert urban-based, trained, and connected health professionals to rural places, we should convert urban-based funds, institutions, and models of care in the education, health, and welfare sectors to non-urban places, to build our own health professional workforce9,21,23.

Current shaping of lived rural and remote space

Rural and remote places are imbued with unique significance for the people who live there46,68-70. Places are filled with experiences, memories, rituals, and traditions that create unique and ever-changing cultures and ways of living68,70. Rural and remote places have unique blends of people who create and reinforce local culture through institutions – including schools, places of worship, and sporting/social clubs – that are meaningful to and valued by the community, and tied with the sense of place and home46,69. People in-place typically understand and value where they live but may have limited influence to change health impacts their community experiences19. Philosopher Albrecht et al developed the term ‘solastalgia’ for the sense of distress, loss, and powerlessness experienced when places change in undesired ways53. Essentially, solastalgia is homesickness for solace previously found at home. This was differentiated from nostalgia where people moved on from places and experienced a sense of loss. For example, interviewees living next to newly developed open-cut mines or experiencing persistent drought expressed distress at the loss of landscape and the memories of place linked with them. They discussed memories of births, deaths, and marriages on the land, and lost occupations such as gardening in a drought or outdoor recreation next to a coal mine and their reduced social interactions due to the new unpleasantness of place. They also described obligations to the land, which they were powerless to fulfil. A First Nations interviewee expressed a loss of connection to Country, resulting in avoidance of place due to the pain of seeing the degradation. A history of colonial thinking about place in Australian policy and planning approaches has removed critical understanding of Country as kin, and diminishes the lived experience of place for First Nations Australians54.

The lived experience of health care in rural places is often one of limited control, decreasing infrastructure, and distant and expensive services, which can result in decisions to simply forgo seeking service at all5,10,39. For example, in Australia, rural and remote people in Australia see a GP less often, and often pay more to do so10. Overall rural and remote Australians have an average of $840 less spent on health care per person, totalling a $6.55 billion dollar expenditure gap between rural and urban places55. This expenditure gap covers publicly and privately funded primary health, disability, and hospital care, despite rural Australians being significantly sicker and dying younger than urban people55. The experience has become so common that rural Australians report living with a sense of resignation to having less access to services and assume that policy changes will not support them56.

Coupled with limited access is an expectation of rural innovation to overcome the lack of capital and infrastructure provided57. Rural places are encouraged to develop solutions without additional resources or personnel, to decrease the cost of rural health services57,58. Given that rural places are often already receiving less funding55, such expectations of ‘frugal innovation’57 may be somewhat unreasonable.

Addressing lived rural and remote space to support spatial justice

Local people understand social routines and practices – such as temporal ebbs and flows, availability of existing resources and those still required60, local customs, local systems, and informal power structures59 – and are more likely to develop systems and processes that will accommodate needs23. A significant and growing body of literature supports place-based approaches to rural and remote healthcare design23,62,62-65. Place-based approaches recognise, value, and mobilise local people in-place to design and achieve outcomes that better meet community needs61-65. Place-based health system design61,62, research63, and recruitment64,65 are increasingly demonstrating better outcomes and sustainability in rural and remote places.

Place-based system design necessarily requires understanding Lefebvre’s concepts of (1) conceived space, to define or redefine the boundaries of the space in question; (2) perceived space, to overcome the need to dictate to rural and remote people what they are entitled to and how they should live; and (3) lived space, by valuing the lived experience and knowledges of local people about their own place and engaging them in developing solutions23. A notable feature of these place-based approaches is not the expectation that rural people innovate alone; rather, that the community is supported in-place by experience, evidence, and resources to adapt systems and process to meet local needs. Place-based approaches appear to acknowledge that resources are required to implement and sustain effective processes61-65. Despite the seeming success of place-based design in changing rural geography and health outcomes, it is not an approach used across most health systems to approach rural and remote health care64. However, increasing place-based approaches to rural health offers opportunities to improve spatial justice by linking local people into designing effective services.

Conclusion

This critical review suggests that framing rural and remote geography in policy and literature as the cause of rural health inequity is short-sighted as it overlooks the role of social processes in shaping geography. Rather than assuming rural and remote people should experience greater cost, inconvenience, and difficulty accessing health care due to geographic location6-8, we suggest rural geography has been shaped by social ideology9,19,21 to result in poor health, and therefore can be reshaped. Through an analysis of this issue using concepts from critical geography and spatial justice, this review has revealed how a process of reshaping the conceived, perceived and lived space is possible, potentially identifying alternative approaches to improving health outcomes for rural and remote communities. Changing how rural spaces are conceived19 to use smaller area-units focusing on health outcomes and opportunity rather than population numbers will allow better identification of local health needs, which may be otherwise overlooked, and allow for tailored solutions and application of resources. Shifting perceptions19 of rural and remote space away from urbanormativity, urban-saviourism, and expectations of self-sustainability to reciprocal valuing of both rural and urban may allow redistribution of resources to build local capacity to manage and provide local health services. Engagement of policy and advocacy with communities in the lived space19 may provide opportunities to build effective solutions in-place using local knowledge, skills and understanding of place. In presenting this case we hope to stimulate a reframing of how rural and remote geography is discussed in health policy and research. As we have outlined, rural and remote geography can too easily be blamed for human decisions to not provide services and infrastructure to rural and remote people. Reframing to focus on spatial justice may allow rural and remote geography to be conceived as a social factor to be shaped, rather than an insurmountable barrier to equity.

Acknowledgements

This study forms part of the first author’s Doctor of Philosophy program.

Funding

No funding was received for this research

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.