Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic, which commenced in January 2020, prompted South Korea to adopt a test–trace–isolate strategy, utilizing advanced technologies, leading to successful outbreak control and low mortality rates1. Much research in South Korea during this period concentrated on infectious disease control2,3. In May 2023, WHO officially declared the end of the COVID-19 pandemic as a global health emergency, gradually restoring daily life towards pre-pandemic conditions worldwide. Our research aims to investigate the enduring impacts of COVID-19 on primary health care, extending beyond infectious disease control.

In South Korea, primary healthcare services are predominantly delivered through public health centers and private clinics. Approximately 97–98% of outpatient visits occur at private clinics4,5, so any changes in the number of private clinics can have a significant impact on residents' access to health care. Throughout the pandemic, primary healthcare providers faced financial challenges due to social distancing measures and patient cancellations of clinic visits due to fear of infection6,7. The financial strain experienced by private clinics as a result of COVID-19 led to some clinic closures, directly affecting the provision of primary healthcare services in South Korea.

Private hospitals and clinics in South Korea have primarily concentrated in the capital area and large cities with high socioeconomic status, resulting in the widening of regional disparities in healthcare resources, healthcare utilization, and health outcomes8. Moreover, research indicates that individuals living in rural areas experience significant health disparities and encounter challenges in accessing healthcare services compared to their urban counterparts9,10.

The objective of this study was to examine the changes in primary healthcare accessibility across all regions of South Korea during the COVID-19 period. While previous research by Son reported no significant overall change in the total number of private clinics during this time11, we hypothesize that variations in the change of private clinic numbers have occurred, depending on regional characteristics. To test this hypothesis, we analyzed aggregated data on private clinics, considering spatial factors and focusing on changes in private clinic openings and closures in each region. Spatial accessibility to health care is considered a critical determinant of healthcare access and a significant contributor to regional disparities12. We expect our study to test the resulting shifts in regional disparities in primary healthcare access during the pandemic by comparing big cities and remote rural areas.

Methods

Study area

In this study we categorized regions based on three types of administrative district: capital area, regional city, and small and mid-sized city/rural area (rural/small city) (Fig1). Previous discussions on health disparities in South Korea have primarily focused on differences between the capital area and non-capital area, as well as those between regional cities and rural/small cities8. In particular, health inequalities in rural areas have been extensively discussed, and, more recently, small and medium-sized cities in South Korea have been experiencing challenges similar to those of rural areas, prompting separate comparisons to big cities13,14.

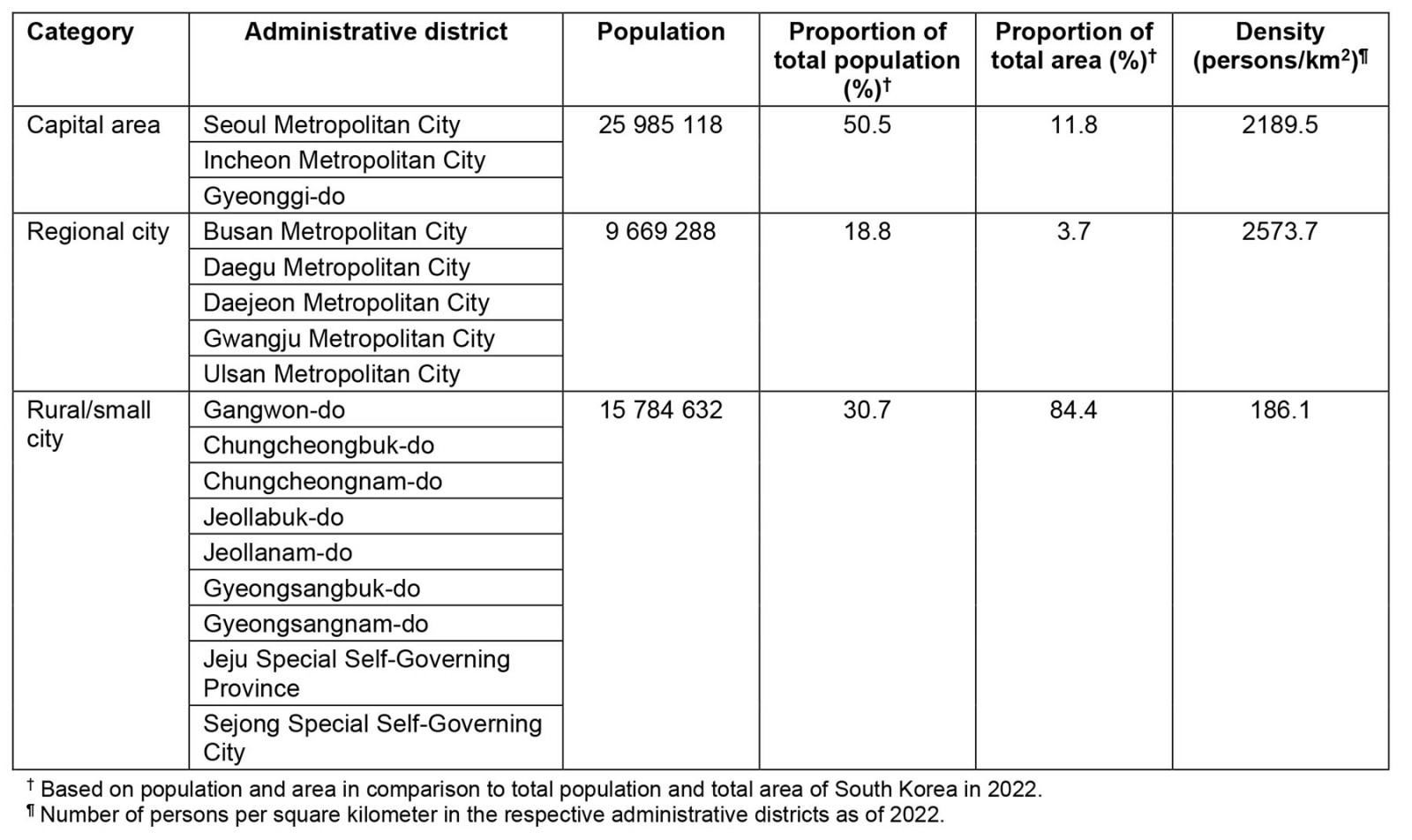

As seen in Table 1, the capital area comprises Seoul Metropolitan City, Incheon Metropolitan City, and Gyeonggi-do, and it is the economic, political, and cultural hub of South Korea. The capital area is home to 50.5% of the country's population15. Given its centrality, the capital area was treated as a single area in this study.

Regional cities consist of Busan Metropolitan City, Daegu Metropolitan City, Daejeon Metropolitan City, Gwangju Metropolitan City, and Ulsan Metropolitan City. With populations exceeding one million, the regional cities play a pivotal role in their respective regions in terms of politics, culture, economy, and transportation.

The small and mid-sized city/rural areas (rural/small cities) encompass 75 cities, Sejong Special Self-Governing City, and 77 towns (excluding five towns included in regional cities), representing areas outside of the capital area and regional cities16. Although these areas occupy 84.4% of the total land area17, the number of residents is small, and the population density is relatively very low.

Table 1: Population data for capital area, regional cities, and rural/small cities in South Korea, 2022

Figure 1: Locations of the capital area, regional cities, and rural/small cities in South Korea.

Figure 1: Locations of the capital area, regional cities, and rural/small cities in South Korea.

Data

This study relied on permit data from local governments, which was publicly disclosed by the national government18. The data pertained to the establishment of private clinics in South Korea. In this study, private clinics referred to healthcare services excluding general hospitals (with more than 100 beds) and hospitals (with more than 30 beds) based on national standards19. Additionally, dental clinics and oriental clinics were excluded from the analysis.

To categorize the private clinics, the first healthcare service indicated in the registration information for the business opening was used. Specifically, essential medical subjects, including internal medicine, general surgery, obstetrics/gynecology, and pediatrics (IGOP), were extracted and separately compared. These subjects are classified as compulsory courses in general hospitals according to Article 3 of the Medical Service Act 202319.

The study compared the years 2017, 2018, and 2019 (before the COVID-19 pandemic onset) period with the years 2020, 2021, and 2022 (after the COVID-19 pandemic onset). The analysis involved examining the number of private clinics opened and closed in each region during these periods to assess the extent of increase or decrease in the number of private clinics by region.

Data were collected from the national licensing records on private clinics that commenced and ceased operations between 2017 and 2022. The information was then organized by the geographical location of each clinic, facilitating an annual calculation of the openings and closures within each administrative unit. To provide a comprehensive analysis, the net change in the number of clinics was calculated for each unit. The data were then reclassified into three distinct types of geographical area: the capital area, regional cities, and rural/small cities. To normalize the data and facilitate comparative analysis, the number of clinics was converted to a per-million population metric, based on the population of the reclassified areas for the respective years. The focus was narrowed down to clinics specializing in essential majors, referred to as IGOP for this study.

A comprehensive count of total primary healthcare facilities, encompassing both private clinics and public health centers, was conducted. This total was then divided by the population of the respective year and area to provide a per-capita perspective on healthcare availability. The data were further categorized into the aforementioned three types of geographical area to enable a focused, region-specific analysis.

Results

Changes in private clinic supply before and after the COVID-19 pandemic

The changes in the number of private clinics were driven by openings and closings per million population (Table 2). In 2020, during the onset of COVID-19, the rate of private clinic increase decreased across all regions, with changes ranging from 2.9 to 4.1 private clinics per million. From 2021, even during the ongoing pandemic and social distancing measures, the increase in private clinics in the capital area and regional cities began to recover. In 2022, the supply of private clinics in the capital area and regional cities exceeded pre-COVID-19 levels. However, in rural/small cities, the supply of private clinics per million people in 2022 was lower than in 2017–2018.

Comparing the average increase in private clinics per million people between the pre-COVID-19 period (2017–2019) and the COVID-19 period (2020–2022), the rate of change in private clinic increase during the pandemic was 26.0% in the capital area, 18.8% in regional cities, and –34.1% in rural/small cities. While the supply of total private clinics increased in the capital area and regional cities during the COVID-19 period, it decreased in rural/small cities. The disparity in private clinic increase between the capital area/regional cities and rural/small cities was already present before COVID-19 but became more pronounced in 2021–2022.

Similarly, when examining the change in essential medical subject clinics (IGOP) per million population, a decrease in the rate of increase was observed in 2020 during the COVID-19 period. The recovery in the supply of IGOP clinics from 2021 was evident in the capital area and regional cities, although the rate of increase was lower compared to the overall increase in private clinics. In contrast, rural/small cities experienced a continuous decrease in the supply of IGOP clinics during the pandemic period. The rate of change in IGOP clinic increase during the pandemic was 0.7% in the capital area, 17.9% in regional cities, and –61.6% in rural/small cities.

The change in number of IGOP clinics in the capital area remained relatively stable before and after COVID-19 pandemic onset, while an increase was observed in regional cities. However, in rural/small cities, the changes in IGOP clinics significantly declined during the COVID-19 period. Regarding the disparity in IGOP clinic increase, rural/small cities initially had a higher supply per capita in 2017, but from 2018 onwards, the capital area and regional cities surpassed rural/small cities (Fig2).

Table 2: Changes in supply of private clinics and private IGOP clinics per million population, 2017–2022

Figure 2: Changes in supply of private clinics and private IGOP clinics per million population by region, 2017–2022.

Figure 2: Changes in supply of private clinics and private IGOP clinics per million population by region, 2017–2022.

Changes in regional disparity in primary health care before and after the COVID-19 pandemic

During the COVID-19 period, the regional disparity in primary healthcare resources was examined based on the number of private clinics and public health centers per million population. Despite the pandemic, the overall number of primary healthcare facilities per population continued to increase across regions (Table 3). When comparing the average number of primary healthcare facilities per million people from 2017–2019 to 2020–2022, the rate of change in primary healthcare per population during the pandemic was 8.1% in the capital area, 8.0% in regional cities, and 3.4% in rural/small cities. The increase in primary healthcare supply per population was more pronounced in the capital area and regional cities compared to rural/small cities.

Notably, there was a reversal in the disparity between regional cities and rural/small cities in terms of primary healthcare per population after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic (Fig3). This can be attributed to the higher supply of private clinics in regional cities, while rural/small cities have not seen a comparable increase in public health centers, which were established to address regional discrepancies in healthcare access.

Table 3: Changes in regional disparity in primary healthcare supply per million population, South Korea, 2017–2022

Figure 3: Differences in primary healthcare supply per million population among regions, South Korea, 2017–2022.

Figure 3: Differences in primary healthcare supply per million population among regions, South Korea, 2017–2022.

Discussion

Healthcare resources in South Korea have tended to be concentrated in urbanized areas, leading to significant regional disparities between cities and rural areas. The issue of healthcare concentration in large cities has been a persistent concern20,21. Simultaneously, there has been a steady rise in the problem of health disparities occurring in rural areas13,14. Our study highlights that this regional disparity in primary healthcare resources was further exacerbated during the COVID-19 pandemic in South Korea. Specifically, the supply of essential medical services provided by IGOP clinics has significantly decreased in rural/small cities compared to regional cities during the COVID-19 period. These changes have intensified regional disparities in primary health care, which is expected to contribute to greater inequalities in healthcare utilization and deepen health disparities in remote cities and rural areas.

Rural/small cities experiencing population decline often have inadequate health infrastructure and poor health conditions22, necessitating the implementation of policies to bridge this gap. The deepening disparity in access to primary health care during the pandemic period in these areas is expected to further exacerbate the problem. For rural/small cities with relatively small populations and situated away from a regional center, various measures are being discussed in the public sector, including the provision of well-coordinated health services23. However, the South Korean government's policy tools for public health care are currently inadequate, with the proportion of public hospitals being the lowest among OECD member countries24. Based on the findings of the present study, South Korea should adopt a more proactive approach, such as securing direct policy tools from the government, including the expansion of public hospitals and public doctors25. This will contribute to enhancing proportional access for vulnerable groups and regions such as rural/small cities while ensuring universal access to essential health care26.

Future research should aim to explore regional disparities in health care resulting from the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic from multiple perspectives, including the availability of other health resources such as medical personnel and medical equipment, patterns of medical service utilization, and health outcomes. Additionally, analyzing the underlying causes through research on barriers and drivers will enable the development of more targeted policy responses. In practice, conducting studies that examine spatial disparities at a micro-level using spatial accessibility analysis methods, such as analyzing the arrival time to healthcare facilities, would contribute to a more in-depth understanding of the specific characteristics of healthcare access disparities.

Conclusion

This study reveals the deepening regional disparities in primary healthcare resources during the COVID-19 pandemic in South Korea. The pandemic resulted in various changes in the number of private clinics across different regions, with notable decreases observed in rural/small cities. This has widened the gap in healthcare accessibility between concentrated urban areas and remote rural regions, posing challenges for vulnerable populations. To address this issue, proactive policy measures, such as expanding public hospitals and the healthcare workforce, should be considered to ensure equitable access to essential health care. Future research should further explore the impact of COVID-19 on healthcare disparities and identify underlying factors to guide targeted policy responses.

Funding

External funding was not received for this research.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no competing interests related to this study.