Introduction

Australia is a vast country with approximately 28% of the population residing outside of a major city1. In Australia, a model to help classify the remoteness of a location is the Modified Monash Model (MMM)2. This model has seven classifications, with MM2 (regional centres) to MM7 (very remote communities) considered to be rural and remote locations2. People residing in rural and remote locations have poorer access to health care, and nurses working in these settings play a crucial role, and are often the first point of contact, for people needing care3.

In 2011, the Commonwealth of Australia produced the National Maternity Services Plan4. This report reviewed maternity services in Australia, highlighting inadequacies in access to, and choice of, maternity care for women living in rural and remote communities and made recommendations aimed at improving access and choice for these women. Despite these recommendations, there has been a staggering 43% closure of rural maternity services in Queensland over the past two and half decades, resulting in a decrease in access and choice for rural women5. Concomitant with the closure of rural maternity units is the expectation and associated stress placed on rural nurses to provide care to pregnant and labouring women.

Preparing nurses for these encounters will always be challenging and courses like CRANAplus and the Imminent Birth Program6,7, developed to address these needs, help to improve remote area nurses’ practical skills but do not focus on addressing psychological concerns. A remote area nurse’s psychological wellbeing, under the additional stress of caring for pregnant women, has not previously been addressed in the literature, despite evidence showing that the state of a remote area nurse’s health and wellbeing can positively or negatively affect the care they deliver8,9. The aim of this study was to provide an in-depth description of the lived experience of remote area nurses who cared for pregnant women in their role.

Methods

Design

Phenomenology, as applied in this context, serves as a methodological approach that facilitates a profound exploration of Heidegger’s Dasein concept, ‘being-in-the-world’10. The world in this context is that of the rural and remote nurse who must care for pregnant women or who live with the anticipation of having to do so in their role. Rooted in the philosophy of phenomenology, hermeneutics emphasises the interpretive nature and importance of understanding the ‘lived experiences’ within the broader context of meaning-making. The term ‘lived experiences’ refers to the first person; however, subjective encounters of being-in-the-world, such as a person’s perceptions, feelings and interpretations of a phenomenon are equally important11.

Acknowledging and embracing the four researchers’ prior knowledge and pre-understanding of the rural and remote nurses’ world, hermeneutic phenomenology recognises that researchers bring their own perspectives and interpretive frameworks to the study10. Two of the researchers for this study were RNs and midwives, one was a midwife only, and one was an RN only. Three of the researchers had worked in rural and remote locations in Australia. This acknowledgement is crucial in ensuring transparency and promoting reflexivity throughout the research process12. Reflexivity becomes a key methodological tool within hermeneutic phenomenology, allowing researchers to critically examine and address their own assumptions, biases and perspectives. By engaging in reflexive practices, researchers can navigate the subjective aspects of interpretation, contributing to a more nuanced and contextually rich understanding of the lived experiences of rural and remote nurses caring for pregnant women11.

Recruitment

Purposive sampling was used for this study13. Nursing participants (who were not midwives) were recruited from a potential 12 healthcare facilities within one rural and remote Hospital and Health Service (HHS) in Queensland, Australia. Only facilities that did not provide maternity services were included (seven in total). A recruitment flyer was posted in each facility and follow-up information sessions via Zoom™ or telephone were conducted with the Directors of Nursing. Nurses interested in participating were invited to contact the primary investigator (PI) to arrange a suitable date and time to be interviewed.

Data collection and analysis

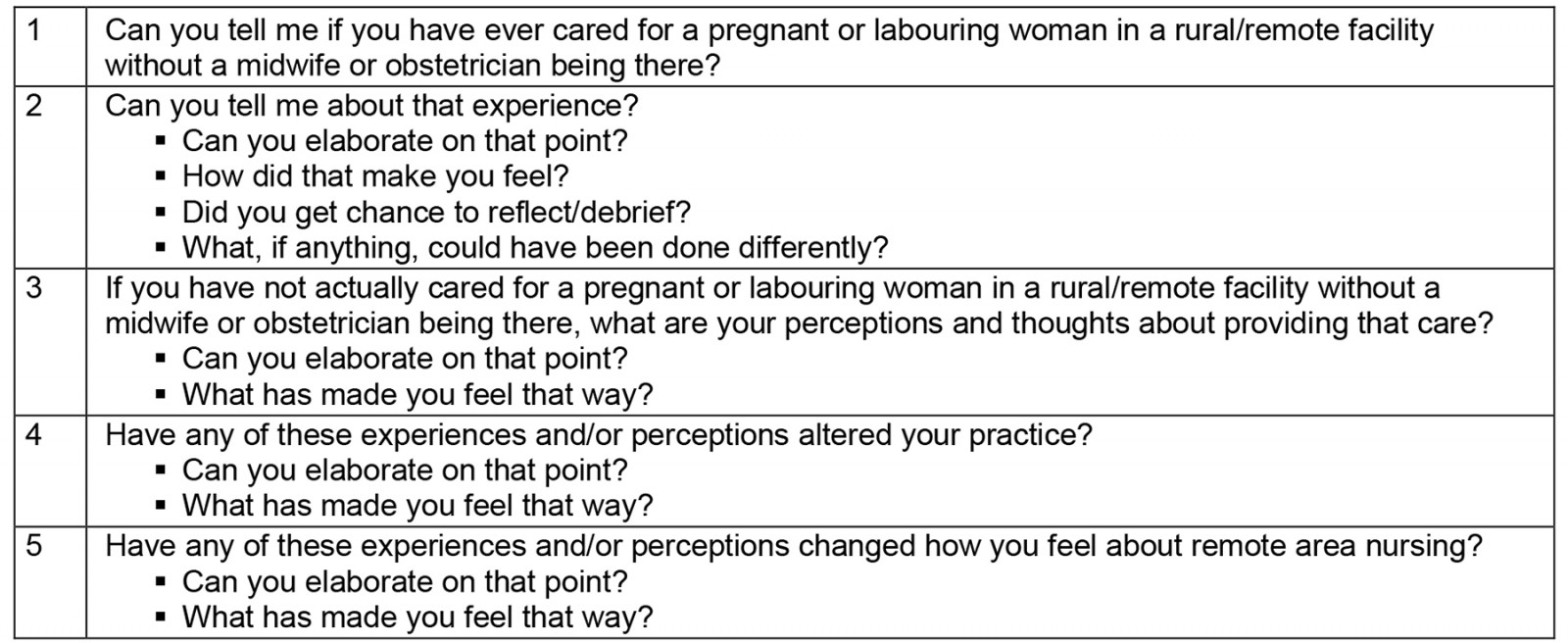

Three pilot interviews were conducted to refine the interview protocol developed by the research team. Semistructured interviews were conducted by the PI by Zoom or telephone and lasted between 22 and 70 minutes. Interviewing by Zoom or telephone offered the PI and participants convenience, efficiency, flexibility, cost-effectiveness and risk avoidance, during the COVID-19 pandemic. Open-ended questions (Table 1) allowed participants to describe their experiences or perceptions of caring for a pregnant woman. All ethical requirements were adhered to stringently, including obtaining informed consent from participants.

Interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim by the PI, who also maintained a reflective journal during and following the interviews. The PI was immersed in the data, reading and re-reading the transcripts while concurrently listening to the audio to gain a deep understanding of the interview in its entirety14. The reflective journal notes were often referred to and built on during this phase. Reflecting on the transcripts alongside writing and re-writing, as suggested by van Manen14, enabled the PI to recognise patterns in the data and commence theme identification. Reflective journalling, copying/transferring of significant text in NVivo v12 (Lumivero; https://lumivero.com/products/nvivo), handwritten index cards, Post-it notes, concept maps and team discussions were all used as valuable tools to aid in data analysis and theme generation. The PI and one other researcher independently coded the data, and all four researchers discussed the data and reached consensus on the final themes.

Table 1: Open-ended interview questions

Ethics approval

Ethics approval was received from Research and Ethics Committees of Townsville Hospital and Health Service (HREC/QTHS/66469) and James Cook University (H8464). Site-Specific Application of Governance was obtained for the seven facilities from the HHS in which data collection occurred.

Results

Participants and themes

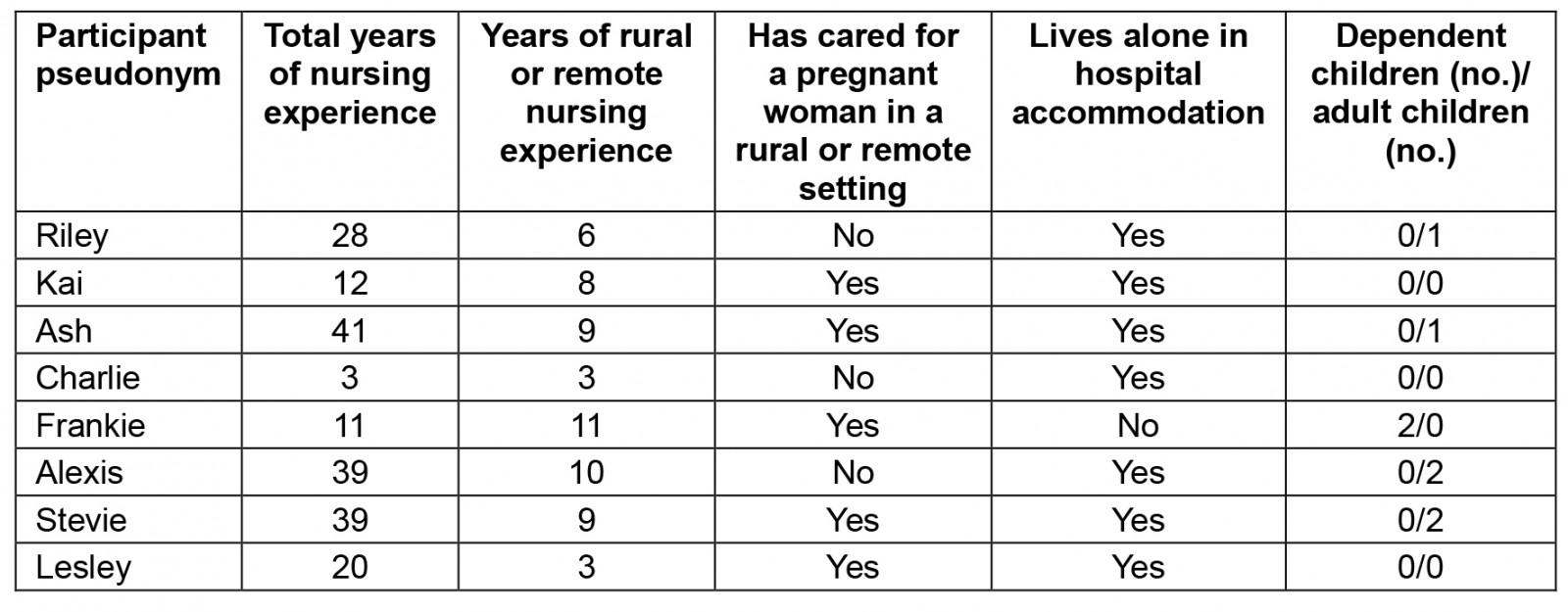

Eight nurses were recruited and interviewed, representing four of the seven facilities (with no maternity services) within the targeted HHS. Data saturation was reached at interview 7 and one more interview was conducted to verify this. To protect anonymity and confidentiality, the four facilities were appointed as locations 1–4, and the maternity hospital in this HHS was termed location 5. All participants were assigned a non-gender specific pseudonym and the pronoun ‘she’ was used for all participants. Table 2 provides a demographic profile of participants. Three major themes were derived from the data: ‘being-in-the-world of the rural and remote nurse’; ‘scope of practice – unprepared or underprepared’; and ‘moral distress’.

Table 2: Demographic profile of study participants

Theme 1: Being-in-the-world of the rural and remote nurse

This theme reflects the complexities of living and working as a nurse in a rural and/or remote location. Interconnected and often unchangeable conditions, such as weather, long distances and lack of resources contributed to the intricacies of the nursing role. Within this theme, ‘the setting’ and the importance of ‘interdisciplinary teamwork’ were prominent.

Subtheme: The setting: The setting refers to the physical and psychological impact the geographical isolation of the health facility had on nurses who worked there. The rural and remote setting was often viewed as unpredictable and stressful by participants for myriad of reasons. Often necessary resources were long distances away, inaccessible because of poor weather or limited technology, and the nurse was often working on her own. While caring for a pregnant woman was not an everyday occurrence, for many in this study, the anticipation of it occurring was an added stressor. Within the rural context, the reality of long distances to a tertiary health facility played a significant role in creating additional stressors for rural and remote nurses, as supported by the following quotes.

Working in a remote setting, you don’t know what’s going to come through that door. (Lesley)

… if I had any issues [in previous non-rural workplaces], I just go round to maternity to ask the NUM [Nurse Unit Manager] and all the midwives and they’re awesome, but you just don’t have that here (Riley). Because up here in [location 2], we have no birthing facilities and [location 1] doesn’t either, so we fly them all out [aeromedical retrieval to a tertiary facility]. (Riley)

You could get telehealth during the day on those computers, but how you’d move those computers around, it would be so impractical for if you were birthing … You could ring the doctors there’s no doubt about it. You could ring them but you were on the phone, you can’t tell anybody what you’re actually seeing. (Ash)

Having little face-to-face access to help and advice, in the form of midwives or doctors, was also concerning for some participants. Frankie considered how the inconsistency of visiting midwifery services affected care in their setting:

It would have been good to have had access to a midwife in a place like [location 3] (Frankie) … I think sometimes there was a midwife that came up to Medicare local, sometimes there was not. (Frankie)

The setting also played a factor in some participants’ ability to attend maternity training and education. Physically travelling to, and the availability, of training in the rural and remote workplace was limited or non-existent, which caused frustration and physical fatigue for some participants. Lesley offered a good suggestion for a more balanced approach to help alleviate the need for rural nurses to have to travel as much:

… we have to travel to [location 5] for each imminent birth course … Obviously, the distance, you know, it’s three days, a six-and-a-half-hour drive to [location 5], then do an eight-hour course and then six-and-a-half-hour drive home. It’s taking staff away from the clinic, the long drive going down there and obviously doing it, and then by the time we get back you’re pretty flustered. Then the next few weeks, you kind of sometimes forget what you’ve learned. … some kind of physical hands-on in the place that you’re working, so somebody’s coming out to you rather than you go into a maternity ward. (Lesley)

Subtheme: Interdisciplinary teamwork: When working in isolated settings and often on one’s own, the importance of connecting with other healthcare professionals was seen as vital. It was evident, when talking with participants, the respect and understanding they demonstrated towards their interdisciplinary colleagues and the need to involve the interdisciplinary team early in the care of pregnant women:

So there’s TEMSU [Telehealth Emergency Management Support Unit] and RFDS [Royal Flying Doctor Service]. We predominantly use RFDS in the first instance that anything is going wrong they need to be involved [as] they are the ones that are coming so we notify them first. (Lesley)

… we were very inexperienced nurses [at the time], and obviously with no midwifery training but I just think because the RFDS doctor, and RFDS midwife were there we felt like we had, I guess, a bit of a safety net. (Frankie)

For Charlie, having the support of her interdisciplinary colleague brought opportunities to learn and expand her own knowledge about caring for a pregnant woman:

It was actually funny that week, one of the local doctors had been talking about certain assessments, and he’d been talking about abdo [abdominal] assessments in particular, and we’d gone through it. And then this girl actually walked through the door, and I did a proper abdo assessment on her. (Charlie)

Theme 2: Scope of practice – unprepared or underprepared

This theme explores the participants’ experiences and perceptions of feeling underprepared to provide care to a pregnant woman. Subthemes that emerged were ‘skills and knowledge’ and ‘education needs’.

RNs’ scope of practice varies depending on their postgraduate qualifications, level of experience and endorsements. Some RNs are extremely experienced clinicians, but this does not mean they feel confident or are competent working in other disciplines, such as midwifery. Because of the close relationship between the disciplines of nursing and midwifery, there is at times an expectation that nurses can care for pregnant women as an extension of their nursing role. The nurses in this study felt underprepared and uncomfortable when these expectations were placed on them, despite being highly experienced RNs:

… as DON [Director of Nursing] and senior nurses, everyone expects you to know everything, and it’s like well I’m only a registered nurse, like you, I haven’t done the midwifery component. (Kai)

… the doctors in [location 3], sometimes they would say, ‘Do I need to come over’ and you’d be like ‘well, this is my assessment, and I’m a nurse’ [not a midwife]. (Frankie)

Subtheme: Skills and knowledge: This subtheme acknowledges that nursing in the rural and remote setting requires extensive generalist skills that often necessitate an extended scope of practice. Participants described both their transferrable existing skills and knowledge and the gaps they see in relation to caring for a pregnant woman. The confidence brought by knowing, even the bare minimum, was discussed by several participants. In their nursing roles, they are confident to critically analyse a situation:

You know, even when I get normal patients come through and I simply don’t know, could be this or that, is ok if not life or death, but when it comes to babies or pregnant women you just think of complications. (Kai)

… [the first time I saw someone] come through with a fishhook hanging out of them, I remember the director at the time going, oh, just look it up or google it, use the PCCM [Primary Clinical Care Manual]. You can fumble your way through that, you can’t fumble your way through a birth or a pregnant mum. (Lesley)

Knowing the basics of maternity care was seen as essential by Alexis and Lesley:

So you’ve got you know the basics, [and] for something where you really don’t know the basics [like pregnancy], I wouldn’t be comfortable. (Alexis)

… I think it should be some kind of rotation or something you do before coming out here … even if it’s, I don’t know, 4 weeks/3-month stint in maternity just to get your basics and have an idea. If you do some kind of rotation program in maternity, then you do learn all these basics of what’s normal and what’s not. (Lesley)

Alexis summed up the experience needed to care for a pregnant woman in a rural and remote location when she discussed junior nurses’ perceptions:

… they don’t know enough to know that they’re not safe. They’re seeing it as just a clinic, they’re not seeing the potential of [maternity] issues that can happen. (Alexis)

Being questioned on their skills and knowledge by healthcare colleagues was confusing for some participants to know what they should and should not do as an RN. Some colleagues were expecting them to have maternity-type skills, whereas other colleagues were not.

… the doctor told her [the pregnant woman] to come in and you [the RN] would listen to the [baby’s] heartbeat. (Ash)

You do hear comments like, you’re not supposed to do that [listen to a foetal heart] because you’re not a midwife. I think there is a little bit of a blurred SOP [scope of practice] boundary there, whether you are supposed to do them as an RN. (Frankie)

To extend their skills and knowledge, many rural and remote nurses undertake extra education, and some obtain certification as a Rural and Isolated Practice Endorsed Registered Nurse (RIPERN).

Kai described the implications of the skills within her extended scope when caring for a pregnant woman in her rural health facility:

You know if they’re sick or whatever then I’ve got to be conscious of prescribing something to her as a RIPERN, is it going to affect the baby. (Kai)

She also spoke about pushing her skills even further, recalling a time when she had been involved in a neonatal resuscitation:

… I’ve never resus’d a child let alone a baby, so I think even though I’ve got the [theoretical] knowledge of resusing a baby … it’s still different. (Kai)

Subtheme: Education needs: This subtheme reflects the educational needs of rural and remote nurses and the challenges they face in accessing and attending education related to looking after a pregnant woman, and how this affects their skill acquisition, maintenance, and confidence. Five participants completed the imminent birth training program15, designed specifically for nurses in rural and remote contexts and found it very useful:

I have done imminent birth, you kind of get a general idea of things that can go wrong. (Lesley)

Attending the Maternity Emergency Care (MEC) course was seen as a priority by Lesley. However, she was having difficulty getting access to the course in a timely manner, despite her desire to better prepare herself. Another participant confessed to feeling overwhelmed with choices and not knowing which maternity course was best to do:

I have waited 9 months to do the MEC. (Lesley)

There’s a heap of stuff out there. It’s just knowing what’s important. What’s the best [maternity] education package to look at? (Riley)

Most of the participants felt, even when they received education in maternity care, the education delivery was not meeting their needs:

There’s [more than] one way you can educate people and do courses. Someone can come to the hospital and have tools, things like that, you can watch videos, you can do it at home yourself or through a hospital. But I really feel strongly, for practical work, experience would be the best way to equip people with education being more hands-on. (Frankie)

… perhaps more practical education in the [maternity] equipment. (Charlie)

I think the [maternity] scenarios need to be activity based; it can’t all be theoretical, practical courses need practical components. (Alexis)

The practical [maternity] courses, I think needs practical components … The last training, I had was on teams. I remember this drug, I remember this thing [aspect of care]. But it’s like, I don’t know how I’d be in the emergency. I thought it was put too much on [Microsoft] Teams. (Stevie)

I think more hands-on [in maternity] kind of stuff. (Lesley)

Theme 3: Moral distress

This theme explores the moral distress displayed by participants in this study because they felt pregnant women were not receiving appropriate care. Moral distress or injury is when ineffective care, lack of knowledge and lack of support16 threaten deeply held beliefs and trust17. Being unable to fulfil a fundamental ethical principal, ‘do no harm’, led to moral distress for nurses in this study18. The nurses reflected on their professional accountability and appropriateness of the care they delivered. Subthemes that emerged were ‘fear’, ‘inadequate and unsupported’ and ‘resignation’.

Subtheme: Fear: This subtheme reflects the fear nurses felt when they cared for a pregnant woman, or the anticipated fear associated with having to provide care in the future. All participants in the study, irrespective of their level of nursing experience in the rural and remote context, displayed, through verbal expressions and body language, a level of fear and anxiety in relation to caring for a pregnant woman:

I was a nervous wreck in case anything went wrong … that was terrifying now that I think about that experience. (Riley)

… it was the premmy [premature] birth, and what could happen with this tiny little baby and that was a bit scary more so than the actual labour process … I remember she was bleeding so much … And I remember being so scared for her because she was so scared … It is very scary, especially when there’s no doctors around that’s when it’s really, really scary … it gets really complicated really, quickly and that’s what I think was the scariest thing. (Frankie)

While many of the participants had not actually experienced caring for a pregnant or labouring woman, their feelings about this being a possibility were evident in their interviews. Ash very strongly voiced her feelings about maternity care:

I sat there for 10 hours going through it [imminent birth training], I thought I was going to throw up. (Ash)

I think the only time I ever think about litigation is obstetrics. (Ash)

Likewise, Alexis and Lesley displayed strong feelings of anxiety at the thought of caring for a pregnant woman, and the potential reasons behind some of their fears:

You know, everything just clenches because you’re like, what could happen? … I think that I’d be vomiting. (Alexis)

I’ve experienced myself with labours that have gone wrong from my own births … I suppose it’s the thought of being out here on your own if something did go wrong, just how devastating that that would be … So the thought of a mum labouring here in [location 3] terrifies me … Your biggest fears obviously, that of the unknown … So, anything to do with midwifery I do get nervous about because I’m not comfortable with that … I get nervous about what you don’t know when that’s not your area … it is one of my biggest fears. (Lesley)

While Lesley had not experienced a pregnant woman in labour herself, her anxiety had developed from hearing about the experiences of others in her remote setting:

Just before I came here, was the last birth where the mum couldn’t wait … she actually birthed in the clinic and she’s pregnant [again] at the moment. So that does make me quite nervous. (Lesley)

Kai’s anxiety stemmed from the pressure of her senior role and potential consequences:

… being the most senior on shift I need help with this [caring for a pregnant woman] I’m not comfortable because it’s not something I’ve done or really have any interest in … it is a little bit daunting as well, and you don’t want to do the wrong thing … I think a little bit anxious you know you’re not only caring for the sick mum, but you’ve got to be also mindful of the child … I think the pressure of having to know lots of stuff is quite hard and it feeds my anxiety as well. (Kai)

Subtheme: Inadequate and unsupported: This subtheme examines how the participants, despite their extensive knowledge and scope in the field of nursing, felt inadequate, unsupported and alone in providing care to a pregnant woman.

Most participants felt inadequate when having to provide care to a pregnant woman:

I think you are talking to the worst person in the world with regards obstetrics, women would be better off coming in to see the cleaner than me. (Ash)

She came in and she said to me, the doctors told me I’ve got to come in you’ve got to listen to my baby’s heartbeat … So, I thought well, where am I going to look for this baby’s heartbeat? because I don’t know … they [the parents] didn’t notice that I didn’t know what I was doing … eventually I found it [the foetal heartbeat] and it took me 25 minutes. (Ash)

I’m not a midwife trained and no mid experience … it’s just fill in gaps and fumbling along, so not really doing everything that they need done. (Lesley)

Not really knowing about what is suitable for pregnant ladies and things like that. (Kai)

You know, if I didn’t know that I didn’t know enough, I’d probably be clueless and fine, but I know I don’t know enough. (Alexis)

The feelings of inadequacy for Frankie involved concern for the pregnant women:

I just think that I like to be able to give people [pregnant woman] the best chance that they have to be healthy … If I’d done four weeks on a maternity ward, I would have felt a little bit better about looking after these patients. (Frankie)

Riley discussed the issue of support, suggesting it needed to be accessible and consistent:

Somebody out there specifically for the remotes, it’s not just you pick up a midwife that’s on shift who might, you know, either know, or have something different to the person that you talked to last week … just having that person out there to contact it’d be good to have a support person or group where we can just tap into. (Riley)

I don’t want to be at this hospital anymore [on my own] I just felt no support. (Frankie)

We are kind of on our own. (Lesley)

Subtheme: Resignation: This subtheme displays the participants’ understanding of the realities of working in a rural and remote setting and how this affects the care they are able to deliver. They appeared to be resigned to the fact they would have to care for a pregnant woman, and when that happens, they would do the best they could with the knowledge and skills they had. This did not mean they wanted to be a midwife or would enjoy the experience, but they knew their professional integrity and their desire to help others would mean they would do what was necessary, despite feeling afraid or distressed by the situation:

I don’t like obstetrics; the enormity of the responsibility hits me. But it doesn’t mean that I couldn’t guess, I would cope though I wouldn’t enjoy it. (Ash)

… I mean, you do what you have to do. (Lesley)

I think I just like to be able to give people [pregnant women] the best chance that they have to be healthy. (Frankie)

I think, going in these remote hospitals, there’s such a high staff turnover that you are often nurse in charge at such a very young [sic] time in your career … the doctors are changing every week as well. These communities need continuity … because I guess it is all about putting the right person [a midwife] in the right job. And I guess the funding is that big, big word. (Frankie)

Discussion

The aim of this study was to investigate the experiences and perceptions of rural and remote nurses, who are not midwives, when caring for pregnant women. Rural and remote maternity unit closures have prompted research that has been focused mainly on maternity service provision19,20 and maternity choice for women21,22. This is the first article to present a new perspective on rural and remote maternity services from the explicit voices of the nurses who are providing care in the absence of midwives.

The specific, unique and complex nature of rural and remote nursing found in this study supports previously published research23,24. The geographical location has formerly been shown to be professionally isolating6 and this was also highlighted in this study. Participants discussed the negative impact of the setting on communication with, and support from, colleagues in the specialty of midwifery when assistance was sought. The physical distances involved in working rural and remote was identified by some participants as a hindering reality. Travelling long distances to attend education incurred expense and affected the quality of skill acquisition and caused issues with covering leave, all points previously identified in the research7,25,26.

The findings of this study show the professional teamwork displayed by the participants and their respect for colleagues. As described in previous research, interdisciplinary practice is essential in the rural and remote setting23,27. Participants in this study acknowledged the high levels of skills and knowledge provided by the interdisciplinary team that they needed to access for advice and learning opportunities. Perinatal statistics show the occurrence of women birthing outside a maternity facility, rising from 702 in 2013 to 1856 in 202128 confirming the reality of nurses potentially caring for a pregnant or birthing woman20. Feeling underprepared for such events was a significant concern conveyed by the participants in this study. As described previously in the literature, the existing generalist nature and extended skills required by the rural and remote nurse8,29 was also echoed by some of the participants. However, the participants did not believe the implications and applicability of these skills extended to pregnancy care, a sentiment consistent with previous findings30. Despite acknowledging the boundaries of their scope of practice, participants disclosed they felt compelled to work outside their scope to try and meet the needs of pregnant women, when no one else was available. This attitude is supported in the literature8,27,29.

Rural and remote nursing often brings advancement into senior roles and a subsequent increased accountability for nurses much sooner than for their metropolitan counterparts8. Corresponding with other research31, a number of participants in this study referred to there being a misalignment between their knowledge and skills and the position they hold within the service, particularly in relation to caring for pregnant women. Participants’ confidence in acquired and transferrable skills did not always relate to competence when caring for a pregnant woman, a finding concurred with in other studies29,32.

Acquisition and maintenance of maternity skills was an area where all participants in this study felt improvements could and should be made. Acknowledgement of the need for maternity education was in agreement with previous research7,8,33-35. However, while grateful for the availability of maternity courses15,30,36 participants in this study felt their educational needs were not met due to difficulties with accessing courses and inappropriate modes of delivery. While these findings were not in themselves new3,6,9,35, participants in this study overwhelmingly felt that hands-on practice and face-to-face learning was imperative for preparedness and capability in this area.

The participants in this study displayed feelings of anxiety, fear and inadequacy when discussing care of pregnant women. Research in Canada, despite the nursing education system differing significantly from that in Australia, found similar feelings from nurses and an underlying ‘fear of a pregnant woman’37,38. There were compelling feelings displayed by participants, both in their verbal responses and in their body language, towards maternity and obstetrics that went beyond the actual experiences to the perceived complications. However, despite feeling scared and underprepared, participants displayed a sense of professional resignation and acceptance for rural and remote nursing.

Although considerable research has explored nursing and midwifery in rural and remote Australia8,39, none has been conducted specifically from the viewpoint of the nurse providing care to pregnant women. The focus for the future provision of rural and remote midwifery services needs to be policy driven and woman focused. However, current care delivery being provided by nurses needs to be acknowledged and addressed through research into maternity education delivery and fitness for purpose. Practitioners providing this care need to be listened to when they say ‘there is more than one way to educate but practical courses need practical components’ (Frankie). The added stressor of caring for a pregnant woman, brought to an existing extensive list for rural and remote nurses8,25,40, cannot be ignored in a climate where nursing recruitment to a rural and remote location is failing41,42.

Study limitations

Despite being sufficient for phenomenological research, the small study size gives a detailed yet HHS-specific view of rural and remote nurses, so it is possible that nurses in other rural and remote locations throughout Australia may have different experiences from the participants in this study. Conducting interviews by Zoom and telephone became necessary because of COVID-19 restrictions. Despite this limitation, all participants were comfortable being interviewed in this way and appeared to speak freely. Research into the use of Zoom technology for qualitative data collection found benefits of convenience, efficiency, flexibility and cost-effectiveness and no difference in quality of data43.

Conclusion

Midwifery services in rural and remote Australia are diminished and inadequate. The findings of this study highlighted three key themes: ‘being-in-the-world of the rural and remote nurse’, ‘scope of practice – unprepared or underprepared’ and ‘moral distress’. Nurses elaborated on the complex nature of working in a rural and remote setting and the associated isolation. Nurses spoke of feeling stressed, fearful, inadequate, lacking in knowledge and skills, and working outside their scope of practice, in relation to caring for a pregnant woman. Acknowledging nurses’ fears and addressing their concerns will better support them in their complex role. Recognition for the significant contribution rural and remote nurses make to the care of pregnant women should be given.

Funding

No funding was received for this research.

Conflicts of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

You might also be interested in:

2010 - Mental health collaborative care: a synopsis of the Rural and Isolated Toolkit

2009 - Adherence to cervical and breast cancer programs is crucial to improving screening performance