Introduction

Most research on disability shows that, globally, persons with disabilities are often excluded and marginalised by society1,2. Exclusion of persons with disabilities is often viewed through biomedical conceptions, dominated by literature from western countries that locates disability on the person and presents it as a tragedy without considering contextual factors3-6. However, there is a shift from the biomedical approach of disability, due to a lot of awareness that disability takes place at the interface of a person and society. Emerging disability research from Africa shows that it is within rural contexts that persons with disabilities are specifically excluded and susceptible to stigma and discrimination7,8 and this is in contrast to the indigenous Ubuntu views of disability, which embrace diversity and promote inclusion.

In a similar vein, researchers documented similar attitudes and stereotypes towards persons with disabilities, which are related to witchcraft and punishment from ancestors9,10. These attitudes were observed after the colonial era; hence, scholars associated them with the impact of colonialism3. Other African scholars have documented the discrimination and the exclusion of persons with disabilities, including by their parents10,11.

Spirituality is culturally significant for persons with disabilities12-14. Evidence shows that spirituality gives persons with disabilities meaning and inner strength to meet the challenges of having disabilities, and decreases their feelings of stigma regarding their disabilities, resulting in positive self-esteem and social support15,16. While spirituality is a broad concept with room for many perspectives, Spencer views spirituality as the recognition that life is more important beyond the ordinary everyday physical needs but includes being part of the divine nature17. In this article, the focus is on African spirituality, because it locates people’s ‘beingness’ with their culture and context. Research has shown that African spirituality is a vital aspect in framing health and wellbeing and in communicating with the sacred to derive meaning and purpose18-20.

According to WHO, disability includes ‘persons with long-term physical, mental, intellectual or sensory impairments which in interaction with various barriers may hinder their full and effective participation in society on an equal basis with others’ (p. 5)21. Wellbeing is another multi-dimensional concept because different disciplines define it in a variety of ways. Cultural differences are also apparent in conceptualizing wellbeing. Langdon and Wiik’s definition of wellbeing provides a holistic view, for it includes the physical, social, emotional, cultural and ecological dimensions of both the individual and the community22, and this is in line with the way Indigenous Peoples experience wellbeing. It emphasises connectedness between people and their context and recognises the impact of social and cultural determinants on the person.

In African society, spirituality occupies the central part of the person and plays a role in connecting a person to the larger community23,24. It is through cultural beliefs, rituals and traditions that spirituality is practised among Africans25. They incorporate spirit into their thinking for it forms part of their knowledge systems and allows them to co-exist with their environment26. This act of humanity is linked to the African concept Ubuntu (‘I am because we are’), and to the idea that nothing is done in selfish ambition. Ubuntu means one’s personhood is defined in relation to the collective – an African worldview that embodies ethics through respect, compassion, harmony, love, social justice and oneness27-29. Considering these aspects of Ubuntu, which characterise inclusion, shows that in African societies inclusion is central to full and effective participation. In defining disability inclusion, Rimmerman suggests that it is about being accepted and recognised as an individual beyond disability, having personal relationships with family and friends, and being involved in social activities (p. 1)30. This is in line with the South African Constitution, which protects the rights and dignity of persons with disabilities while supporting their inclusion in society31. While some research has been conducted on disability in rural settings in South Africa32-34, there is limited research into inclusion of persons with disabilities in cultural rituals, and this impacts on our understanding of what happens within these ritual spaces and the power held behind them.

The data presented in this article builds on our previous research. This forms part of a PhD project that explored lived experiences of persons with disabilities, their inclusion in three life-cycle rituals of AmaXhosa from birth to adulthood, and describes how these experiences contribute to their health and wellbeing. The three rituals were:

- Efukwini, literally meaning ‘behind the door’, refers to when a woman enters seclusion for 10 days, and the space is regarded sacred to give birth35. The significance of the ritual is to protect the child from evil spirits. Seclusion is followed by imbeleko (a ceremony of slaughtering of a goat) to introduce the child to the ancestors.

- Intonjane (female puberty rite) is a girl’s rite of passage to womanhood, performed between a girl’s first menstruation and her wedding36. The girl undergoes seclusion for the duration of the ritual.

- Ulwaluko is a traditional male circumcision rite to manhood in which boys learn about acquiring their identity and responsibility37. The detailed process culminates in circumcision, just before boys are taken to seclusion, away from their families38,39.

The present study had two aims. The first was to explore the experiences of persons with disabilities in Xhosa rituals and traditions. The second was to describe how these experiences contribute to their health and wellbeing. A focus was placed on lived experiences of persons with disabilities and their inclusion in cultural rituals, as these are deemed important for a person to fully function in rural communities. Attention was also given to the exploration of how the rituals provide health to the wellbeing of the person with disability.

Methods

Context and setting

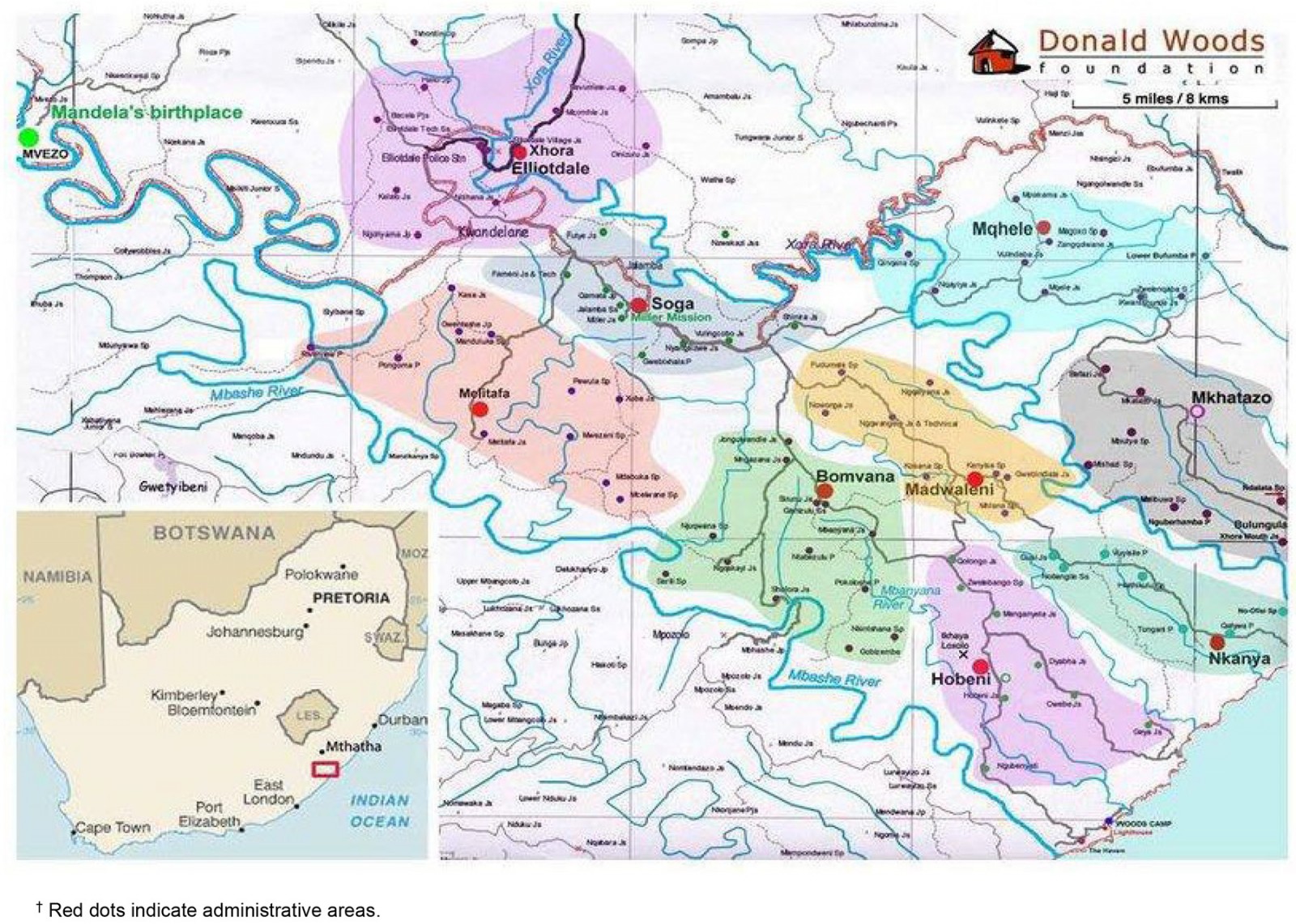

Figure 1 shows the study area of the Elliotdale/Mbhashe local municipality in Eastern Cape province, with red dots indicating the eight administrative areas presided over by the local chiefs. Each administrative area has clusters of villages managed by chiefs and chieftains.

The people who reside in this area are called AmaBomvane, with the prefix ‘Ama’ being the plural of ‘Bomvana’, a subgroup of the Xhosa nation who speak isiXhosa as their first language. AmaBomvane are a tribe still holding strongly to their customs and rituals. The villages are arranged into clusters and are managed by chiefs, with each village cluster having a clinic, schools and shops.

The municipality has a total population of 253 490 people40. The roads are gravel with dongas (large potholes) that make travel by car difficult. Spring and summer bring reasonably high rainfall that assist subsistence farmers with green pastures and grazing fields for their stock as well as growing mealies (maize) and vegetables for their family use. However, there is no published data of how many people with disabilities reside in Elliotdale; only a few studies on access to health care for people with disabilities have been published34,41.

Figure 1: Map of Elliotdale/Mbhashe local municipality in Eastern Cape province, South Africa, showing study sites.†

Figure 1: Map of Elliotdale/Mbhashe local municipality in Eastern Cape province, South Africa, showing study sites.†

Position of the first author

As a Xhosa-speaking person who grew up in a home rooted in Xhosa traditional customs, where life-cycle rituals were performed for every individual, the researcher learned to interact with Indigenous people earlier in life; hence, we use an African lens to approach the study. The first author is a Black African South African woman, but nevertheless not an insider to the cultural group. In addition, the researcher’s 10 years of experience in teaching learners with intellectual disabilities has served as a bedrock for approaching vulnerable groups with humility, empathy and respect.

Study design

A qualitative design underpinned by critical ethnography and the case study method was employed. The relevance of critical ethnography in this study lay in its ethical responsibility, to address issues of unfairness and injustice in society42. Critical ethnography had an emancipatory effect, by exposing the everyday struggles and resilience of persons with disabilities, which are oftentimes unrecognised in society. Also, it enlivened issues of equality between the researcher and participants, as both were co-creating knowledge in the process. The exploratory case study method covered the contextual situation of people with disabilities as this was deemed fit for the study43. Both methods provided detailed descriptions of situations, events and people about their experiences, without trying to fit people’s experiences into predetermined responses44.

Background and training of the research assistant

The research assistant was identified through the assistance of the chief as a woman who had good standing in the community and had experience in working with researchers in previous studies. A user-friendly research assistant training manual was developed by the researcher prior to fieldwork. A 2-day training of the research assistant took place at the chief’s homestead. The content introduced her to the fundamental elements of the study, role expectation before and after the interviews, data-collection activities and ethics. Role-plays to check the research assistant’s comprehension were done after each session. Because she was familiar with the participants, issues of confidentiality, rights, sensitivity and respect were emphasized during training through the administration of informed consent to participants. This was meant to prevent issues of coercion that might occur during the interview process. The exact role of the research assistant before the interviews was to inform people about the study in a way they could understand, and to distribute study brochures. Also, she assisted with co-facilitation of interviews: checking recording equipment, administering informed consent forms, keeping track of the interviews, note-taking and expanding notes within 24 hours, making sure all materials were labelled and debriefing with the researcher after every interview session. The researcher double-checked if all processes were in order before the start of every interview and that all were aware of the participants’ rights.

Recruitment of participants

The recruitment process was done through the local chiefs, who arranged community gatherings at their homesteads for the researcher to explain the study to the people. Villagers who were present at the initial meeting disseminated information by word of mouth. Fifty participants comprising 28 females and 22 males were recruited. Of the 50 participants, 19 had disabilities. Table 1 shows participant demographics of disabilities. The identification and selection of participants were guided by purposive sampling and snowball technique45,46.

Table 1: Overview of study participant demographics of disabilities

| Gender | Age group (years) of participant or parent/caregiver† | Nature of disability | Acquired/congenital disability | Number |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 4–6 | Physical (hearing) | 1 congenital | 1 |

| 7–12 | Physical | 3 acquired | 3 | |

| 13–16 | Intellectual | 2 congenital | 2 | |

| 40–65 | Physical |

3 acquired 1 congenital |

4 | |

| Male | 6–12 | Physical |

3 acquired 2 congenital |

5 |

| 13–16 | Intellectual | 2 congenital | 2 | |

| 40–65 | Physical |

1 acquired 1 congenital |

2 |

† Data for children (aged ≤16 years) with disabilities were obtained from participating parents and caregivers.

Inclusion criteria

Study participants were from one of three municipal villages (Hobeni, Gusi and Xhora) in Elliotdale and generally met one or more of the following inclusion criteria: being a custodian of Xhosa culture (an elderly man or woman who holds and practises Indigenous knowledge and healing), a person with a disability aged 18 years or above, a parent of a person with disability aged less than 18 years or a caregiver of a person (of any age) with disability. Some exceptions were made to these criteria, because in these communities things are done collectively due to the reciprocal nature of relations. We applied sensitivity by not excluding people who would add value to the study and contribute to the richness of data.

Data-gathering methods

Key informant interviews, focus group discussions, observations, a journal and field notes were used to collect data in the villages of Hobeni, Gusi and Xhora (Table 2). The researcher and the research assistant conducted the interviews, and the researcher stayed and lived in these communities for 4 weeks. There were seven focus group discussions and 11 key informant interviews. Key informant interviews were conducted in participant homes, while focus group discussions took place at the chiefs’ homesteads. All interviews took place in July 2021 and were recorded and transcribed verbatim from isiXhosa into English, then translated back into isiXhosa to ensure accuracy. A Xhosa language teacher assisted with verifying the translation. The duration of each interview was 90 minutes.

Table 2: Participants attending key informant interviews and focus groups

| Study method | Participant type | Number of participants | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hobeni | Gusi | Xhora | ||

|

Key informant interview (11 interviews) |

Person with disability | 1 | 5 | 0 |

| Traditional healer | 2 | 0 | 1 | |

| Traditional circumcision surgeon | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| Social worker | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| Focus group discussion (seven groups) | Male elder | 10 | 6 | 0 |

| Female elder | 6 | 0 | 0 | |

| Traditional birth attendant | 5 | 0 | 0 | |

| Parent of person with disability | 4 | 0 | 0 | |

| Caregiver of person with disability | 8 | 0 | 0 | |

Data analysis

Content analysis method was used. The first stage involved de-contextualisation, where the researcher and the research assistant read data word-by-word to capture deeper meanings underlying lived experiences of persons with disabilities47. All transcripts from data were broken down into smaller meaning units (codes) that gave insights and answered the question set out in the study aim. Labels that summarised the data were assigned. After the identification of the meaning units, data were recontextualised, both the researcher and the research assistant checking if all content had been covered regarding the aim of the study. This process was followed by the formulation of categories accomplished by dividing content based on the questions used when data were collected. The codes and categories chosen served as the basis for final analysis and interpretation. Guided by the refined codes and categories, themes and patterns that captured the insights, key messages or phenomena were identified and contextualised into the research, and lastly, interpreted48. In addition, observations were contextualised to uncover nuanced insights, and this helped in identifying patterns and relationships through the assistance of the chiefs, elders and people in the community to gain deeper insights in relation to the study.

Trustworthiness of findings

Credibility

Credibility was achieved through member checking by both the researcher and research assistant. Data accuracy was checked immediately after the interview sessions, as a quality control measure to avoid loss of information49,50. Analysed scripts were exchanged to allow each person to re-analyse and ensure that there were no omissions and to see if the same themes emerged.

Transferability

The research journal, field notes, observations and other tools used for data gathering provided a ‘thick description’ to enable the reader to understand the study within the context of AmaBomvane, feeling and sensing as if the reader were there. However, caution would be needed in relation to making inferences about other populations such as AmaBomvane because the study was contextually based.

Confirmability

Triangulation employed throughout the data-collection phase helped to corroborate the research findings, and to enhance the credibility and objectivity of the study. Every claim made in the results derived from the data and could be confirmed by other researchers.

Dependability

An audit trail was established by the researcher where every point of data gathering was indicated – including, time, date and place – to ensure reliability and consistency. Member checking was also utilised by asking participants to give feedback regarding accuracy and interpretation of their narratives. This process helped with additional insights and to gain more clarity.

Ethics approval

Ethical approval was obtained from the Stellenbosch University Health Research Ethics Committee, (reference S20/08/188) in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration. The principles of ethical conduct such as informed consent, reimbursement for participants, confidentiality, autonomy, justice, non-maleficence and beneficence were explained to the participants. All participants in this study were of consenting age (18 years and above), who were able to make independent decisions. They were not forced to participate in the study and were given an opportunity to consult with family members if they wished. Participants were assured of confidentiality and that no data would be disclosed carelessly or inadvertently; only the research team would have access to the data. All communication was in isiXhosa language. Participants were also informed of the value and contribution of their involvement on the study and were asked to sign an informed consent form when there were no questions asked. For people who did not have formal education, a thumb print could be used to indicate consent to participate. Refreshments were provided during the interview process as part of Ubuntu, and an amount of R100 (A$8) was given to each participant as a token of appreciation for the time spent at the interviews.

Results

The importance of rituals to rural people emerged as the core function in forging disability inclusion in their sacred and spiritual places, and provides an alternative to the understanding of disability. Four key findings are presented in this section, the first being description of the Indigenous worldview of AmaBomvane, as shown in Figure 1. It is followed by three core themes that emerged from data: ‘we are not trying to change disability’, ‘our tradition allows our relationships to co-exist with persons with disabilities’ and ‘the soul is not disabled’. Each theme is further illustrated by quoting participants directly.

The Indigenous worldview of AmaBomvane

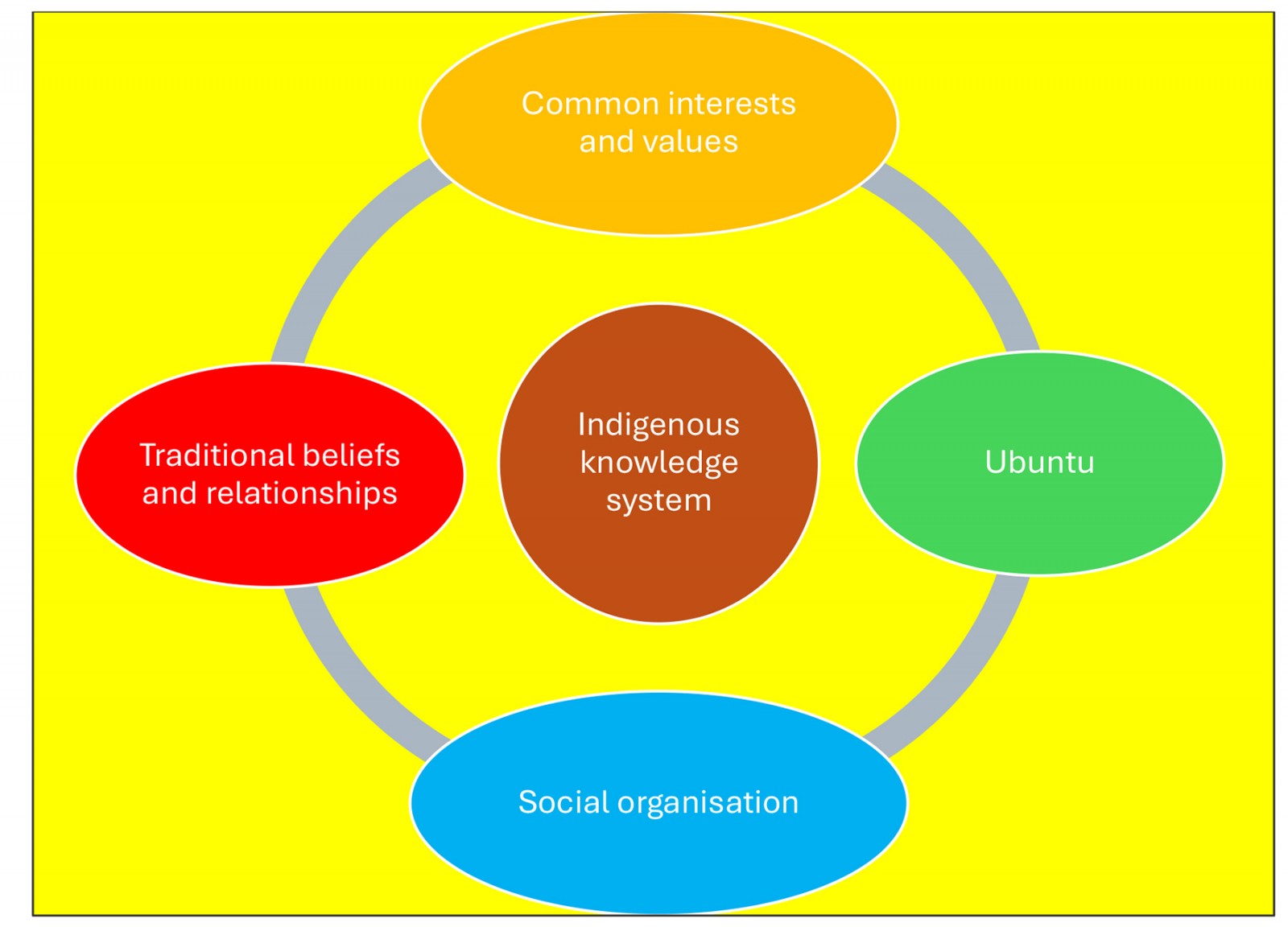

Figure 2: Indigenous worldview of AmaBomvane.

Figure 2: Indigenous worldview of AmaBomvane.

In this study, the Indigenous worldview of AmaBomvane was discovered through a combination of observations and interaction, first with the chiefs, then the elders and then the people in the communities. In the case of AmaBomvane, it is their Indigenous knowledge system (which includes all other values shown in Figure 2) that holds people together. The circular and flux Indigenous worldview of AmaBomvane represents a spiritually orientated society where African spirituality informs every facet of human life and cannot be separated from everyday life.

The social organisation is characterised by homesteads, each with an agnate (from the same male ancestor) male who is linked to other clan members outside the homestead, and this becomes a social structure. This social structure accounts to the chief as the head of the community. An ever-present understanding of the wholeness of existence is maintained, because AmaBomvane share a fundamental belief in the sacredness of relationships enacted through rituals, customs and traditions, to the fulfilment of their spirituality. Because each family is linked to a wider group, people share common ancestors and common interests that bind them together, creating a continual process of engagement. Due to the inclusiveness of this dynamic Indigenous worldview, people participate directly in social activities. Underlying all this is Ubuntu, displayed in their affection for others, including strangers, and the respect bestowed throughout their daily interactions. AmaBomvane acknowledge that they are not without the other, and this has a stronghold in their daily lives. Commitment to this value system is perceived to benefit the entire collective, hence inclusion of persons with disabilities is part of the AmaBomvane way of life. State of relatedness is perceived to go beyond the social unit of the extended family, which occupies a homestead.

Theme 1: ‘We are not trying to change disability’

Participants’ strong adherence to the same rituals and spirituality influences their interpretation and way of life. The value accorded to their definition of disability is based on the principles of Ubuntu, which is their Indigenous worldview characterised by respect and empathy. Hence, participants find it necessary for all to be treated equally because rituals are seen as part of health and wellbeing deserving to be accessed by everybody. A person with disability recounted:

Disability does not mean nothing. The rituals that we do here change nobody from disability to non-disability but are for the wellbeing of the person. Our rituals heal the person and by doing them we are preventing something that could cause ill-health beyond disability. You do not have to be sick to do the ritual. (person with disability: 1)

The acknowledgement that rituals bring no change to a person’s disability status but provide health benefits for AmaBomvane appears common among participants and is expressed as part of family solidarity toward persons with disabilities. Also, these rituals help in addressing misperceptions on why they are done for persons with disabilities. An elder in a focus group reported:

I am not to trying to change what God has created, but I am giving my daughter health for her wellbeing. I am doing her a family ritual as expected. We want them to feel welcomed just like anybody else in the family. I cannot say she does not qualify for the ritual because she is disabled. Why must her role be of less importance than other family members? She did not become disabled because of a ritual but [was] born with a disability. (female elder: 1)

Evidence from the participants’ narratives indicate that health benefits are accessible through rituals. The recognition of the important roles and rights of every member in the family, especially of persons with disabilities, strengthens a sense of belonging for persons with disabilities.

A common view shared by participants showed that participation of persons with disabilities in rituals is a social norm shared and practised by families in the rural community of AmaBomvane. In addressing exclusion, a male elder summed up a view shared by most male elders:

You cannot exclude him; you start from the beginning until the end. No matter how things turn out, what is important is to do the ritual for the person. (male elder: 1)

Theme 2: ‘Our tradition allows relationships to co-exist with persons with disabilities’

Embracing diversity and difference is seen in participants’ compassionate culture, which is embracing and characterised by Ubuntu. The emphasis on seeing themselves in others is linked to their beliefs and customs that all living things contribute to the cycle of life equally. A strong sense of community that accommodates persons with disabilities is prevalent among participants, as was reflected in an interview with parents of persons with disabilities:

My two daughters undergone ukuthomba (female puberty rites) at the same time, one has intellectual disability, and the other has not. She had to undergo ukuthomba because she is a woman, and this is our custom for women, handed down to us by our ancestors. This ritual strengthened the family bond. Our tradition allows relationships to exist with the person with disability from efukwini (birth rites) to adulthood, which is how we live. (parents of person with disability: 2)

The interconnectedness present among AmaBomvane attests to the moral responsibility to live in harmony with those around us. This results in persons with disabilities showing the ability to tackle inclusion in community life and making affirmations that showcase their role in the community. One person with disability recounted:

I feel I am part of the community and I participate in rituals that take place in my village. I am no different to other people and I have a family of my own. My two daughters, my husband and my in-laws and I think people in this community do not see me as disabled. There is no disability here, but harmony. (person with disability: 3)

The positive influence of space and place shared in participants’ narratives shows their recognition of persons with disabilities in community life, which includes rituals and other social activities and is aligned with valuing others, as reported by one traditional healer:

When we have rituals in the community, persons with disabilities form part of us and sit with us because they are part of the community. We do not ostracise them and they eat food with us, and when we drink traditional beer, we drink from the same calabash. There are no special vessels for them. (traditional healer: 4)

Participants were also forthright in sharing views to show how individuals and communities should consider treating persons with disabilities. Emphasis seems to have a deeper spiritual basis that links disability to God’s creation, as reported by a group of elderly men:

Here kwaBomvane, the treatment of persons with disabilities is inclusive because we were all created by God and that is why we exclude no one in rituals. They are like us, they are no different to us, we see a person not disability. (male elder: 5)

In agreement with the above quote, a traditional healer expressed the role of spirituality in understanding disability. It appears that spirituality plays a vital role in addressing stereotypes and exclusion of persons with disabilities:

We are all equal before God and there is no special ritual for a person with disability. When we talk about a person with disability we are talking about a human being, because the blood is the same, and is also a family member. (traditional healer: 2)

In view of participants’ narratives, it seems that relations in Indigenous spaces present an amicable understanding based on Ubuntu, which continues throughout the community.

Theme 3: ‘The soul is not disabled’

In reflecting on the importance and necessity of doing rituals for persons with disabilities, participants see disability as not part of the person, because to them the actual person is the ‘soul’. A person with disability who is a leader of his clan said:

Our customs and rituals work in the soul of a person for his wellbeing. Disability is in the body while the soul has no disability, therefore, the ritual gives persons with disabilities composure and stability. Our ancestors work in the soul, same as rituals. (person with disability: 7)

These rituals appear to be used as efforts toward one’s resilience, which is essential to health and wellbeing. In sharing the same sentiments, participants used different ways to demonstrate disability as outside the person:

Disability is just like a blanket any other spirit is wearing. It is outside the body, therefore, is not an obstacle. (male elder: 8)

Even if one has disability, you do the ritual. His soul is not disabled because it is the spirit that gets healed or cured. (traditional circumcision surgeon: 9)

There is no discrimination of persons with disabilities. All the rituals are done for them because the soul is not disabled. For example, if I am an elder brother and I have a disability, when a ritual is done, my younger brother would lean on me to whisper everything and take directive from me. They respect that I am an elder brother, even when disabled, they are my mouthpiece. (male elder: 10)

It appears that, according to the participants, the soul is one ability that no disability can steal away, as it resembles the ‘real’ person. Hence, inclusion of persons with disabilities in rituals and or in community activities seems non-negotiable. The respect accorded to a person with disability who has a duty to preside over rituals shows that disability does not take away a person’s responsibility to lead. Thus, participants do not see an impediment whose difference needs transformation when they look at a person with disability.

The three themes demonstrate the valuable contribution of participants in embracing inclusion of individuals in their communities, including persons with disabilities, and this has been realised through the philosophy of Ubuntu, which is embedded in their worldview.

Discussion

The study focus was to explore experiences of persons with disabilities of Xhosa rituals and traditions and to describe how these experiences contribute to their health and wellbeing. The study highlights old but rediscovered ways of conceptualising disability, showing the need for further research on disability in Africa and elsewhere. Data presented in the findings show that this is an Indigenous community, very much connected to their land, with cosmology that informs who AmaBomvane are, where they come from, and what their personal role in life’s larger picture might be. In support of interconnectedness among people who share common beliefs, Kyalo51 points out that rituals bind people to core principles and ideals upon which an entire community exists52-55. This reciprocity is, among other things, made possible by the participants’ traditional way of life, with chiefs and elders playing a significant role in providing knowledge, practices and beliefs to enable stability of the communities. Also, the reality of living within fenceless compounds, knowing that a neighbour can come at any minute to ask for what is lacking in their household, and whose sharing philosophy allows them to practise Ubuntu to others, increases trust among villagers. The practice of ancestral reverence based on respect seems to be the cornerstone of their existence – perceived to promote healthy communities.

Data from this study showed that the concept of disability in this rural setting considers contextual factors that affect persons with disabilities. This differs from more developed countries, whose conceptualisation of disability is characterised by normalcy56-58. For these Indigenous people, health determines all aspects of their lives including their environment, animal and plant life, and communication with their ancestors, who they believe to be protecting them59-61. According to AmaBomvane, health means functionality – an ability to perform daily tasks in the community, and this serves as the measure of health62; therefore, health is measured according to the village. Based on their understanding of health and sickness, the Bomvana people see disability as a foreign concept used to encourage stigma and discrimination. When a person with disability can function in the community and fulfil the obligations of AmaBomvane, the person is not disabled. Thus, AmaBomvane look beyond disability – to them disability does not pose a threat because of their integrated way of life.

Evidence in this study reveals that the spiritual and the physical co-exist: everything is impregnated with spirit and cannot be separated. Hence, the participants made an assertion that when a person is born with a disability, nothing can change, and it is not their intention to change it. A person with disability is seen as a family member, deserving all the privileges enjoyed by others. Within literature, this finding is supported, especially in research done among Indigenous Peoples63-65. However, their view that a person deserves rituals in his or her honour, like all family members, illustrates their attempt to transform negative views on disability and remove shame associated with a disabled person in society. Also, this show of Ubuntu suggests a paradigm grounded in interconnectedness, where people see themselves in others. The acknowledgement of God in relation to disability appears common among AmaBomvane, for they are linked to God through ancestral reverence occurring through the performance of rituals. In support of this view, Mtuze points out that AmaXhosa believe in God (the Supreme Being) and approach him through their ancestors, who serve as intermediaries66.

The interpretation of disability by AmaBomvane, using the example of the soul, dismisses the exclusion and negative thoughts people have towards people with disabilities. The use of ‘blanket’ (a symbolic ‘cover’, rather than the real person), challenges the dominant ideologies of disability packed in the production of knowledge that occupies the academic space67.

When the Bomvana say ‘the soul is not disabled’, this supposes that disability does not affect the soul, for the ‘soul’ is where life is. This analogy indicates that the soul is where interaction with ancestors occurs for the wellbeing of the person, and this does not mean they turn a blind eye on impairment, but ‘it does not matter’ to them. Instead, they embrace impairment as part of being. Also, this explanation of disability expresses tolerance, kindness and Indigenous rights to self-determination from an Indigenous perspective68. Inclusion could not be better emphasised than letting persons with disabilities experience the shared group feeling of participating in their customs, because to AmaBomvane these rituals carry a therapeutic effect on the person’s health and wellbeing and that of the community.

Limitations of this study include the difficulty recruiting a larger sample of persons with disabilities. It was unclear whether this was because the study was done during the COVID pandemic or due to severe winter weather. The plan was to have a bigger sample of persons with disabilities with different types of disabilities, given the study was about experiences of persons with disabilities.

Conclusion

This article shows that, in the case of AmaBomvane, it is spirituality that occupies their unique Indigenous worldview, which imposes a sense of accountability to ensure inclusion of persons with disabilities. As a result, inclusion of persons with disabilities promotes a disability approach, which embraces diversity, difference, human dignity, respect and empathy toward persons with disabilities, as well as protecting their rights. Participant data shows that wellbeing is an important aspect of a person’s life and restores balance, hence the desire to continually connect with both ancestors and others for stability.

Participants’ narratives demonstrated that universalising disability is likely to ignore the realities affecting people in rural communities. It has been pointed out in this article that access to rituals for persons with disabilities provides a structure for the person, which guides towards stability and compliance within the collective. This stability and compliance are linked to understanding the purpose of life, which in participants’ views may only be realised through life cycle rituals. Thus, participants view paying homage to the ancestors as bringing health and happiness, which fulfils the African saying that ‘healthy, happy homes make healthy, happy villages’.

It is only through these rituals that participants anticipate the presence of a golden thread of goodness that connects all life from the youngest to the eldest person, and that makes a person with disability experience their identity. The attempt to present the strong case of AmaBomvane to replicate the interpretation of disability may prove useful not only for persons with disabilities in the Global South, but also for the disability scholarship in its entirety. To shift from exclusion towards inclusion of persons with disabilities in society, positive thinking and replacing negativity with positive attitudes is a step in the right direction, which would yield positive outcomes. This study has created a shared space to encourage and elicit the voices of persons with disabilities while adding to the growing body of knowledge systems.

Recommendations

There is a lack of disability research on Indigenous groups in sub-Saharan Africa, which is an opportunity to craft new ways of conceptualising disability and contribute to wellbeing of persons with disabilities. It is evident that more research on disability and the contribution of Ubuntu in shaping tolerance and respect for others is needed, because it is seen to improve inclusion of persons with disabilities and reduce social exclusion.

Advocacy work on disability driven by persons with disabilities can have a positive impact in bringing awareness, education and understanding about disability. It can remove the stereotypes about persons with disabilities and can be an opportunity for people to learn about the capabilities of persons with disabilities.

Funding

No funding was received for this research.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

You might also be interested in:

2017 - Indigenous clients intersecting with mainstream nursing: a reflection

2016 - Towards understanding the availability of physiotherapy services in rural Australia

2008 - They really do go