Introduction

Globally, nearly 50% of the population live in rural areas, while just 36% of nurses work in these locations1. According to the Canadian Association of Rural and Remote Nursing, approximately 10.8% of Canadian nurses worked in rural locations in 20162. Rural regions have been defined in Canada as communities with populations of less than 10 000 people2,3, although ‘rural’ is inconsistently defined across the literature in different countries4,5. In this article, the term ‘rural’ is used to broadly capture both rural and remote locations, in whatever way these terms are being used by the authors of the studies included. Rural nurses provide care in various settings, such as public and community health, inpatient units, emergency departments, long-term care, outreach, and outpatient settings2. However, rural settings often have limited access to resources and specialists compared to urban settings, varying levels of communication technologies, and greater susceptibility to environmental disasters2. Rural nurses typically have a broader scope of practice than their urban counterparts, as they are presented with a range of healthcare concerns and diverse populations6. While some rural nurses specialize in mental health and/or substance use (MHSU) care (eg MHSU prevention, harm reduction, treatment, and health promotion), most have a multi-layered, generalist practice, working in multiple settings (eg hospitals and primary care)7. In this article, ‘rural MHSU nurses’ or ‘rural MHSU nursing’ refers to the practice of both rural MHSU specialist and rural generalist nurses who provide MHSU care as a part of their nursing practice.

Within Canada, an estimated 20% of the population experience an MHSU disorder, such as generalized anxiety disorder or major depressive disorder, in any one year8, and nearly half of the population worldwide are expected to have had or develop a MHSU disorder by age 75 years9. People living in rural regions tend to have disproportionately higher rates of mental health challenges10 and poorer mental health outcomes11 than those in urban areas. Further, rural people in some regions, such as British Columbia, Canada, face a 30–50% higher risk of a fatal toxic drug poisoning (drug overdose) compared to urban areas12. Moreover, rural residents typically face greater stigma related to mental health13 and substance use14 compared to urban residents. Compounding these inequities, MHSU services may be absent, difficult to access, or inadequate13,15. In this context, rural nurses are often the first point of contact and the primary professional support for those with mental health challenges, across healthcare settings7.

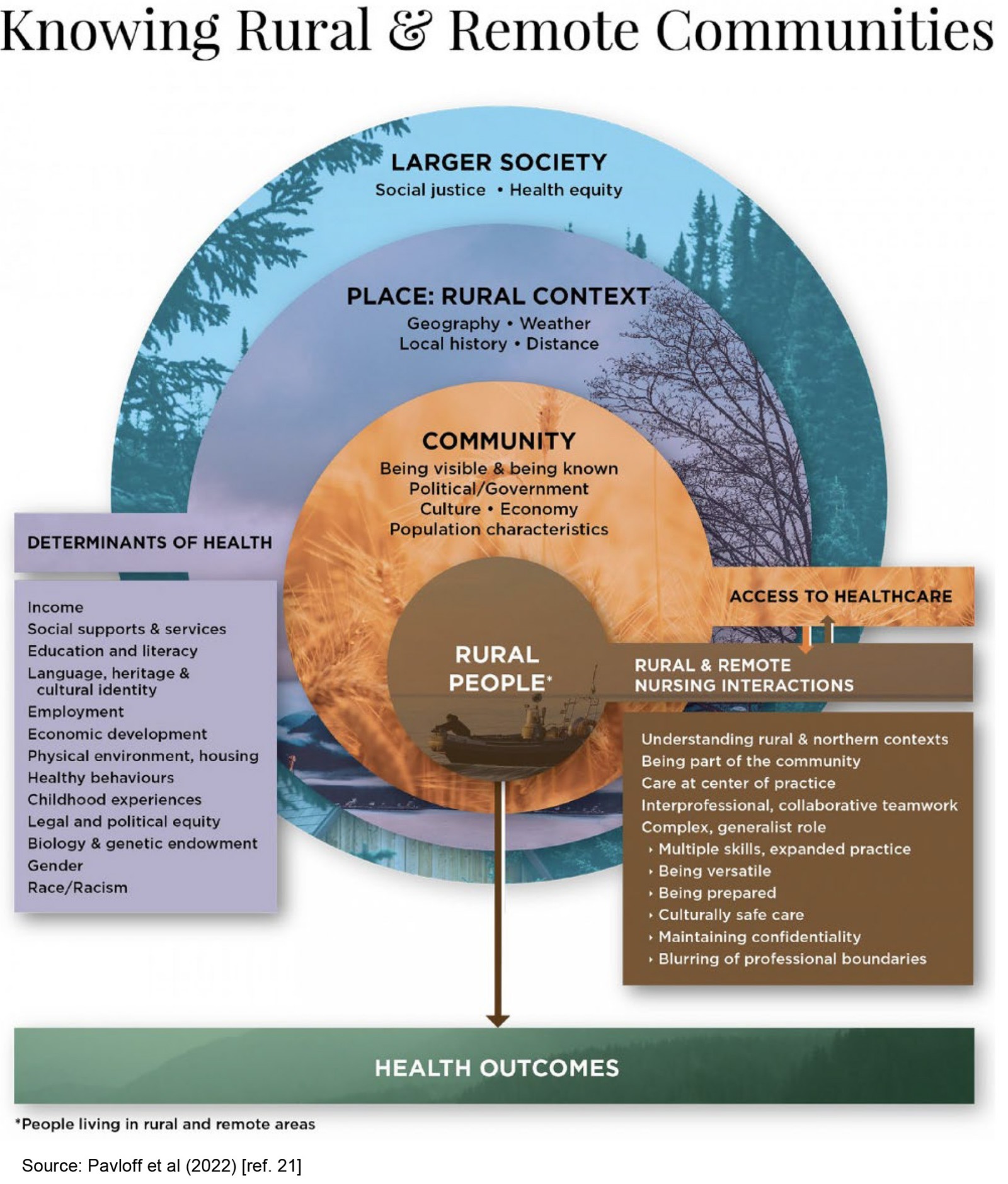

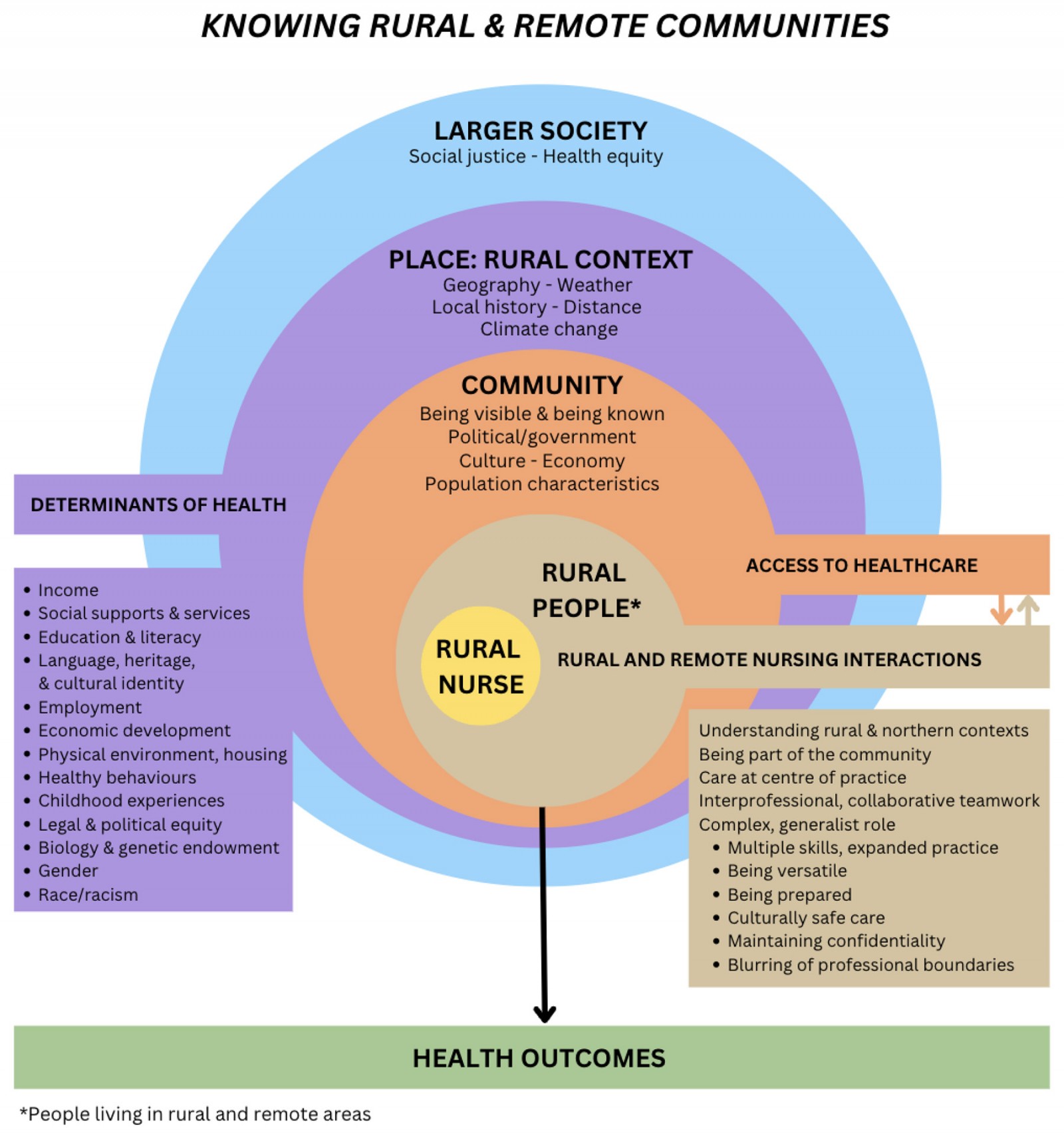

International research has been conducted on rural MHSU nursing, highlighting the difficulties of working in isolation with limited resources7,16,17. However, although literature reviews have been conducted on rural nursing (eg on rural health nursing research18, rural continuing nursing education19, and evidence-based practice and rural nursing20), to the authors’ knowledge no literature reviews have been published on the overlapping areas of rural health, MHSU care, and nursing. Therefore, evidence is required on the practice realities of rural nurses related to MHSU, as the health of rural communities is deeply connected to their work6. To improve insight into this practice area, the professional practice framework for rural nursing practice, Knowing the Rural Community: A Framework for Nursing Practice in Rural and Remote Canada2,21, could be used to explore the rural MHSU nursing practice (Fig1). The framework2 was developed to support rural nursing education, clinical practice, policy, and research2. To date, there is no published evidence that the framework2 has been examined within MHSU research, policy, or practice. Thus, this scoping review aimed to examine the rural MHSU nursing literature in relation to the framework2, to expand the understanding of this practice area and explore the congruence between the literature and the framework.

Figure 1: Knowing the Rural Community: A Framework for Nursing Practice.

Figure 1: Knowing the Rural Community: A Framework for Nursing Practice.

Methods

Scoping review

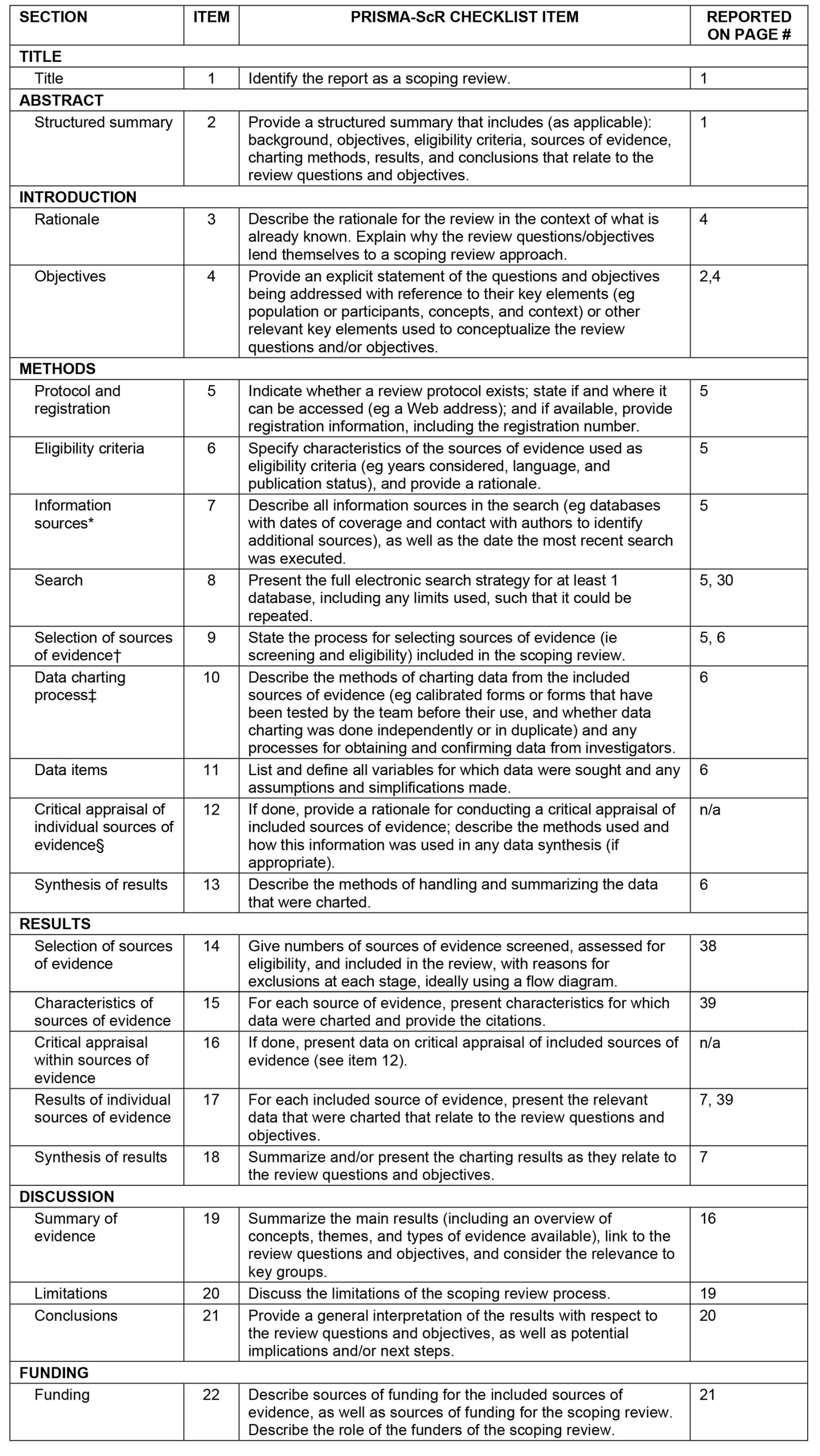

The depth and scope of rural MHSU nursing literature internationally was unclear, and therefore, a scoping review22 was chosen to guide a broad exploration of the literature. For this review article, a scoping review was defined as ‘a type of knowledge synthesis, [that] follow[s] a systematic approach to map evidence on a topic and identify main concepts, theories, sources, and knowledge gaps’23. Given the complex and heterogenous nature of rural MHSU nursing7,10,17, a scoping review is particularly suited to synthesize the existing literature comprehensively, thereby facilitating the identification of both well-established evidence and under-explored areas that may require further investigation23. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) checklist23 (Appendix A) was used to guide the report of this review. No a priori review protocol was created for this scoping review.

Search strategy

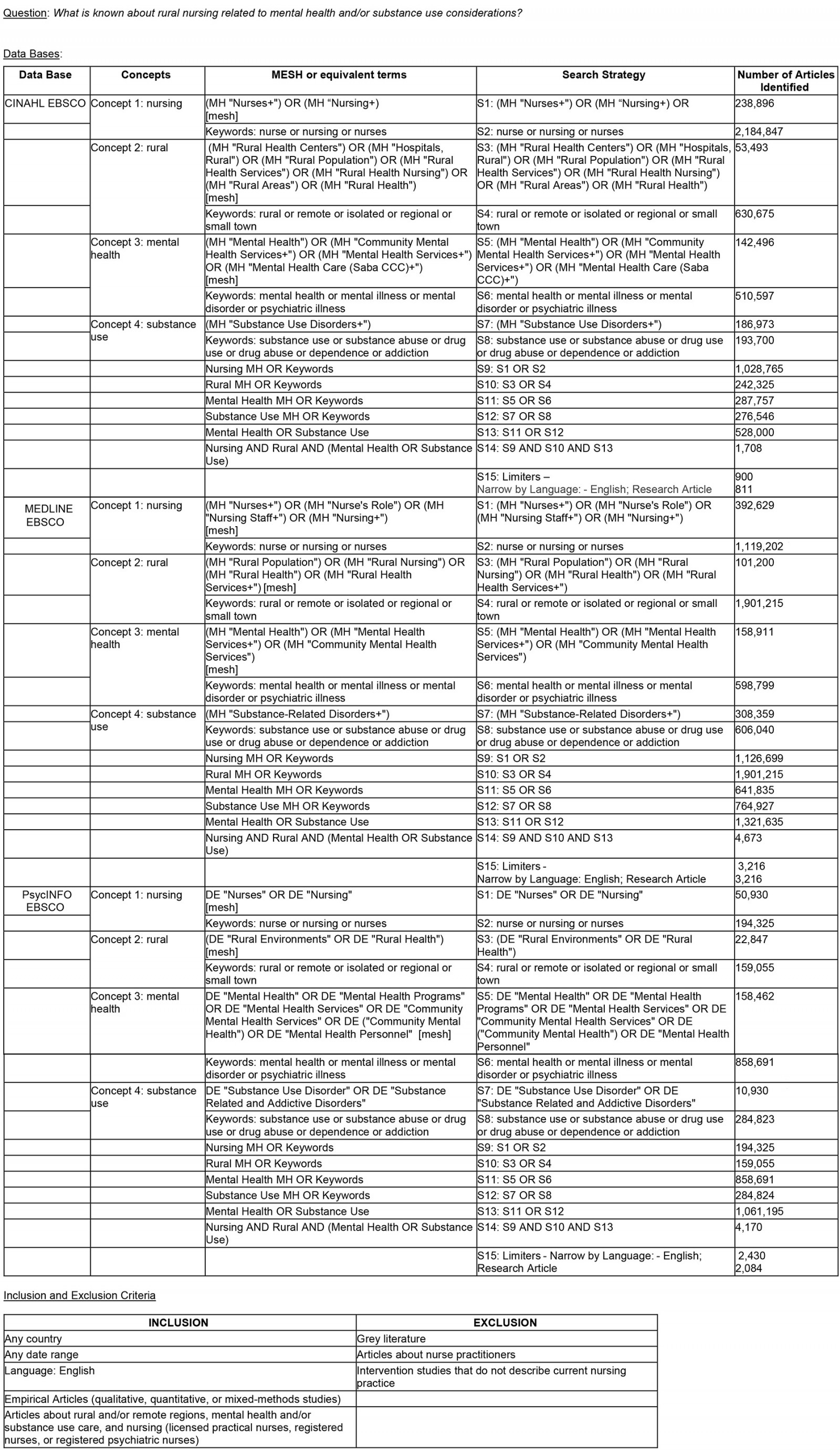

CINAHL, Medline, and PsycINFO databases were used to search for articles that addressed the research question. Searches were conducted from May to August 2023, using standardized search headings and keyword searches based on the concepts of 'nursing' AND 'rural' AND 'mental health' AND 'substance use'. The search strategy was developed in consultation with academic librarians (Appendix B). Boolean operators (AND/OR) were used to retrieve relevant articles. Inclusion criteria included any date range; any country; language (English); qualitative, quantitative, or mixed-methods scholarly (peer-reviewed) articles; articles that included considerations about rural and/or remote regions, mental health and/or substance use care; and nursing (eg licensed practical nurse, registered nurse, or registered psychiatric nurse) practice considerations. Exclusion criteria included grey literature, articles about nurse practitioners due to differences in scope of practice, and intervention studies that did not describe current nursing practice.

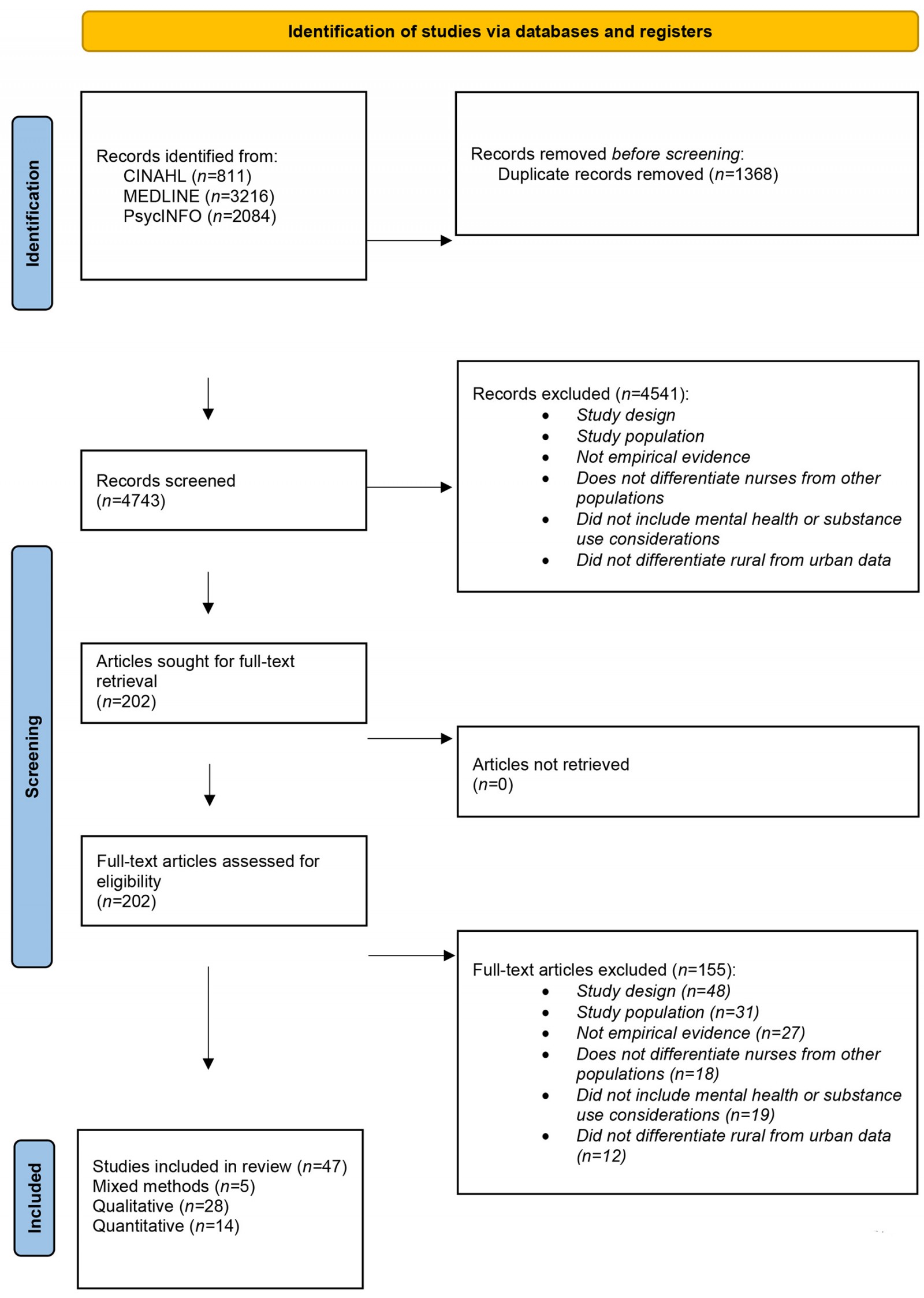

In total, 6111 articles (CINAHL, n=811; Medline, n=3216; PsycINFO, n=2084) were retrieved and imported into Covidence (2023), a literature screening and data extraction tool. Duplicate articles were then removed (n=1368). Next, the titles and abstracts of 4743 articles were independently screened by two reviewers (ST and EK or DJ), excluding 4541 articles for irrelevance based on study design, study population, lack of empirical evidence, lack of differentiation of nurses from other populations, lack of MHSU considerations, and lack of differentiation of rural from urban data. Then, 202 full-text articles were independently assessed by two reviewers for eligibility (ST and EK or an undergraduate research assistant), excluding 155 articles for (1) study design (n=48), (2) study population (n=31), (3) not empirical evidence (n=27), (4) not differentiating nurses from other populations (n=18), (5) not including MHSU considerations (n=19), and (5) not differentiating rural from urban data (n=12) (Appendix C). Data on study characteristics and any data relating to rural nurses’ involvement with MHSU care were manually extracted from 47 articles; the range of publication dates for these articles was 2012–2023. Data were managed in a Microsoft Word document and NVivo v14 (Lumivero; https://lumivero.com/products/nvivo), and extracted into relevant framework2 categories.

Synthesis

The included articles were synthesized, first describing the study characteristics (type of research design, country, healthcare setting, and participant characteristics). Results from individual studies were deductively mapped to the framework2,21 categories: (1) rural people – rural and remote nursing interactions, (2) community and access to care, (3) rural context, and (4) larger society, starting with a focus on the micro level (rural and remote nursing interactions) and expanding to the macro level (larger society). Results were compared and contrasted to see how they fit with the framework2. If results could not be coded using the framework2 categories, an inductive approach to code the data would have been implemented; however, all data fit within the framework2 categories.

Results

The included studies were conducted in 16 different countries and in diverse practice settings (Table 1). In total, 47 articles relating to rural MHSU nursing were examined: 28 qualitative, 14 quantitative, and five mixed-methods studies (Table 2). Articles reviewed contained data from primary data sources (surveys, questionnaires, community mapping, focus groups, and/or unstructured or semi-structured interviews) and secondary data sources (document analyses and literature reviews). The studies examined or included only mental health considerations (n=22), both MHSU considerations (n=21), or only substance use considerations (n=4) within rural nursing practice. Where demographic information was included, most nurses in the studies were women, registered nurses, with an age range of 21–70 years. Data were synthesized into four overarching themes within the framework2: rural people, community, rural context, and larger society.

Table 1: Scoping review study countries and practice settings

| Characteristic | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Study country | |

| Australia | 15 (31.9) |

| US | 8 (17.0) |

| Canada | 7 (14.9) |

| South Africa | 5 (10.6) |

| Cameroon | 1 (2.1) |

| Greece | 1 (2.1) |

| Guatemala | 1 (2.1) |

| Indonesia | 1 (2.1) |

| Ireland | 1 (2.1) |

| Kenya | 1 (2.1) |

| Mongolia | 1 (2.1) |

| Poland | 1 (2.1) |

| Scotland | 1 (2.1) |

| Saint Kitts and Nevis | 1 (2.1) |

| Sweden | 1 (2.1) |

| Tanzania | 1 (2.1) |

| Setting | |

| Hospital | 14 (29.8) |

| Primary care | 11 (23.4) |

| Community mental health | 7 (14.9) |

| Community health | 7 (14.9) |

| Emergency department | 6 (12.8) |

| Urgent care centre | 4 (8.5) |

| Long-term care | 3 (6.4) |

| Mental health | 3 (6.4) |

| Other (nursing station, obstetrics, education, or not specified) | 3 (6.4) |

| School | 3 (6.4) |

| Home care | 2 (4.3) |

| Hospice/palliative/end-of-life care | 2 (4.3) |

| Indigenous community | 2 (4.3) |

| Remote practice | 2 (4.3) |

| Maternal–child health | 1 (2.1) |

| Mobile mental health unit | 1 (2.1) |

| Substance abuse program | 1 (2.1) |

Rural people – rural and remote nursing interactions

Generalist, complex rural nursing role: Rural nurses are part of the community, serving the people they live among. Within the framework2, the rural nursing role is described as complex and generalist, requiring a versatile, prepared, culturally safe nurse to work in a dual role (ie where their personal and professional roles overlap). Over one-third of the studies reflected this multifaceted rural nursing role4,10,17,24-37, with 15 of the studies addressing the generalist and multiskilled approach that is required for rural MHSU care4,7,10,17,25,26,29,30,33,34,36-40. Many of the nurses reported having to contend with a high workload4,24,25,29,32,39,41, and subsequently, the MHSU needs of some rural people25 were challenging to address or prioritize and minimal time was left to devote to the nursing team’s or community’s mental health education needs36,39. In addition, the generalist role was associated with increased responsibilities4,24-26,29,36,42 in the context of a changing healthcare landscape, which included rising substance use, increased youth mental health challenges10, and increasingly complex care needs10,24,26,29,33.

Workplace safety: Nine of the studies also indicated that rural nurses faced a significant risk of violence in their nursing interactions due to patient mental health, substance use, or other reasons7,24,25,27,28,36,43-45. Some rural nurses may have access to law enforcement support for violence intervention31, while other nurses may be unable to involve police or other emergency services due to a lack of these services36. In three studies28,43,44, workplace culture was reported to compound and contribute to the risk of violence against rural nurses through complacency or normalizing workplace violence.

Workplace violence was exacerbated for rural nurses whose personal and professional lives intersected as a result of their dual roles. Rural nurses in smaller communities feared being targeted outside of the work setting by people who had been aggressive in the past44. The dual nursing role was also noted to add to ethical dilemmas and complicate an already multilayered rural role4,25,36,45. However, in one study46, most rural home-visit nurses felt capable of navigating their dual role, such as interacting with the rural people they worked with in the community, outside of their practice interactions.

Intersectoral collaboration: Four of the studies described the importance of collaboration, highlighting the positive impact of partnerships between nurses and Indigenous workers28, families41, and other community members10,28. In several studies, the nurses’ role was described as being part of an interprofessional team to provide rural MHSU care10,24,29,33,39,41,47,48. One study identified that the rural school nurse role was not well recognized as supporting child and youth mental health, and thus there were missed opportunities for collaboration42. In contrast, Burch and Stoeckel described how some school nurse offices are places children and youth may go to feel safe when experiencing physical or mental health issues29.

Nurses in one study described how beneficial it was to have a mental health nurse embedded within rural emergency departments for collaborative, integrated mental health care39. Another study emphasized the need to understand the community’s concerns related to mental health, and partner with community services to address these concerns10.

Cultural safety and trust: Cultural safety and trust were underexplored facets of nursing practice. Cultural safety is defined here as a process and outcome where people feel safe and respected within health care, as determined by the person accessing care49. Only three studies underscored the importance of culturally safe care28,36,50 and the need for adherence to cultural safety policies and access to cultural safety training36. The need for trust to facilitate care between rural nurses and the people they work with35,40, including youth51, was also noted. For example, nurses in one study35 describe how confianza, an Indigenous Guatemalan concept, is translated to trust in English; however, culturally defined, it is really ‘a trust based on respect and the duty to honor an interpersonal relationship’35 and is pivotal to facilitating mental health care.

Preparedness for practice and role implications: The nurse’s experience of ‘being prepared is a consideration in the framework1, albeit a relatively minor one. However, since nurses’ experiences were described in 20 out of 47 studies, we have provided a detailed description of nurses’ experiences here, Nurses’ personal experiences may influence their nursing interactions or capacity to do their job4,7,10,17,24-29,31,35-39,41-43,52. Many rural nurses in the reviewed studies expressed a lack of MHSU experience, training, or knowledge4,7,10,17,25,26,28,29,31,33,34,36-38,41,42,52-54, and reported low confidence providing mental health care10,24-26,35,38,42. Rural nurses in one study41 identified their lack of counselling skills required for comprehensive mental health care. Moreover, some nurses were coping with stress, burnout4,28,36,43-45,55, feelings of being undervalued in their role30,42, and other distressing emotions24-27,35,45. However, five studies10,29,36,45,50 noted that rural nurses are resilient and that they worked hard to provide good care despite the challenges faced by these nurses and the rural people they worked with. This commitment to provide care supports the mental health of the communities of which rural nurses are part.

These findings highlight the complexity of the multiskilled, generalist rural nurse role. Rural nurses, balancing their dual roles of community member and caregiver, may feel unprepared for but committed to delivering MHSU nursing care. This reality may be compounded by rural community considerations.

Community and access to care

The framework2 considers community to include the political, cultural, social, and economic context in which health care is situated, including access to care. Nearly three-quarters of the studies underscored the challenges faced by rural nurses and their communities, with inadequate and/or poor access to healthcare resources described in most studies4,7,10,17,24-29,31-42,45-47,51-53,56-62. These deficient healthcare resources included absent or insufficient security measures7,10,26-28,36, a lack of funding40,41,59, a lack of facilities and/or services4,17,29,34,35,42,47,51,59,62 or limited service hours33, inadequate equipment27,37 or mental health screening tools38,42, absent MHSU policies5,31, inadequate access to training4,7,17,26,34,36,37,39,42,52, limited access to medications41,53,62, fewer or a lack of cultural resources36,58,63, inadequate staffing (eg inadequate baseline staff and/or no specialized onsite MHSU support)7,10,17,26,27,31,32,34,36-38,41,47,52,56,57,59, insufficient time to complete their work4,7,29,36,39, lack of access to peer support42, a lack of (or delayed) critical incident debriefing36,43,45, and deficits in leadership support25,28,36,45. The lack of resources can create challenges for nurses when addressing the social determinants of health that may impact MHSU29,35.

Additional challenges that impacted access to MHSU care included difficulty referring or supporting rural people through the complex mental health system10,31,35, transferring people to a higher level of care outside of the community7,10,24,35,37,58, helping people access mental health care via telephone10,24,46, or accessing mental health assessments after business hours10.

Jones and Quinn described the challenges that the interprofessional care team, including nurses, may face when providing substance use care in remote communities, including no pharmacy, limited nursing station hours, and the need for people to travel out of community for opioid use disorder treatment initiation (eg buprenorphine–naloxone)33. These systemic challenges contributed to an uncoordinated system of care, where MHSU care31 and physical health care59 were absent or fragmented. Limited onsite or community support was identified to be a significant barrier to providing quality MHSU care in some studies4,10,24,35,42,62. Further, 11 of the studies found that many rural nurses worked in isolation within their clinical practice setting, where they may be one of a few or the only healthcare provider on shift7,24-27,32,36,37,42,45,46.

Support: In contrast to the many challenges faced by rural nurses and their communities, two studies reported that some nurses felt well supported by leadership (eg received psychological workplace support, such as debriefing, after an extremely distressing incident)27 or had adequate peer support to navigate MHSU care in their practice setting24. In one study, leadership support, peer mentorship, and past experience with teaching helped improve nurse self-efficacy for providing mental health education (eg postpartum depression education)64.

These findings suggest that rural nurses and their communities face significant challenges when trying to provide or access MHSU care, including a range of insufficient or absent resources. These varying challenges are important to understand because rural healthcare systems are a part of, and integral to, rural communities.

Social determinants of health: Seven studies included data about nurses’ perspectives on the social determinants of health in relation to the MHSU experiences of community members such as income, housing, and food insecurity. In three studies35,46,65, nurses expressed an awareness that rural people’s MHSU challenges can be in response to or influenced by the social determinants of health such as poverty, interpersonal stress, and familial factors, thus requiring support that is tailored to a person’s multifaceted experience. Two studies32,59 described how rural people with mental health challenges experienced financial insecurity and subsequently had challenges accessing in-person medical care.

Burch and Stoeckel described how school nurses were aware that child and youth MHSU challenges were related to the social determinants of health, such as poverty and housing insecurity29. Furthermore, some nurses and school staff tried to alleviate stress related to food insecurity by providing free lunches, doing the students’ laundry, or helping them with hygiene. It was also noted that geographic isolation may intensify stress related to the social determinants of health, such as poverty46. Nurses in one study66 discussed that the mental health of rural people is more resilient than that of urban people due to adversity (eg living in harsh environments).

Rural context

Rural context refers to the geographical, climate, and historical environment in which rural healthcare services are embedded21. In 18 of the studies, the rural context was described by nurses as an important consideration when providing MHSU care. Working in remote and sparsely populated areas meant that nurses were often working in geographical isolation4,7,10,24,26,27,32,36,42,46, or they had to travel far to provide care29. Some nurses worked in remote, mountainous regions48, while others worked in locations that were only accessible by aircraft27,58. Prohibitive geographical distance was also a barrier for rural people who required MHSU services outside of their communities33,35,46,51,59,62. A lack of, or unreliable, internet access or cell phone coverage in the area may prevent some rural people from accessing telehealth MHSU care46,60. Five studies described rural climate considerations, including poor road7,46,62 and weather conditions7,51, or extreme weather events such as flooding32, that made geographically isolated rural environments more difficult to live in. Nurses in two studies described the importance of knowing local current and historical community issues as part of the context of rural people’s mental health10,29. For example, rural school nurses were aware that youth they worked with were negatively affected by significant family issues such as abuse, homelessness, and substance use29. These findings highlight the geographical and climate challenges that impact healthcare access within the rural context and begin to explore the importance of knowing a rural community’s history.

Larger society

Larger society refers to societal values and beliefs, and includes social justice and health equity considerations21. Nineteen studies identified health inequity considerations related to ‘larger society’ when comparing rural to urban communities. Five studies highlighted the disproportionate mental health challenges in rural compared to urban communities, with fewer healthcare providers or services (eg specialized services or psychiatric beds) to meet this greater need4,7,10,56,57. Two studies found significant inequities between rural and urban communities, where there were fewer mental health nurses in rural regions of Australia61 and fewer nurses who staffed rural Indigenous substance use programs in the US63 compared to urban regions. In two studies32,59, nurses felt that rural communities face greater barriers (eg staffing and service shortage, geographic, and economic challenges) when rural people accessed in-person medical care, compared to urban communities. Additionally, 14 studies identified that mental health stigma was a pervasive issue in rural communities7,10,25,26,32,34,35,39,41,47,52,58,59,62. Stigma was described as being directed toward rural people with mental health challenges from rural nurses10,25,62 or other community members32,34,35,39,41,59,62. Additionally, stigma was directed toward rural nurses from urban healthcare providers when training in cities26, and from community members toward rural mental health nurses7. In six studies, stigma toward rural people with mental health challenges was noted to limit their engagement with health services32,34,35,59,62 or impede comprehensive care41. While many of the studies included ‘larger society’ considerations including rural MHSU inequities and stigma, nurses in only one study described the role for mental health nurses in decreasing stigma for the people to whom they provided care39.

Table 2: Extracted articles relating to rural mental health and substance use nursing (n=47)

| Author(s), country, setting(s) | Purpose | Research design | Sample | Data collection | Main study findings | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Ambikile, et al (2021)38 Country: Tanzania Setting(s): hospitals and health centres MHSU |

To assess nurses' and midwives' awareness of IPV-related mental healthcare and associated factors to encourage care provision. |

Quantitative. Cross-sectional survey. |

Purposive sample. Nurses and midwives from hospitals and health centres in the seven districts of Tanzania's Mbeya region; remote areas. Rural nurses: n=568. |

Cross-sectional, anonymous, self-administered survey developed based on the 2013 WHO IPV Clinical and Policy Guidelines. | In hospitals, higher professional nursing and midwifery education (AOR: 1.207; 95%CI: 0.787–1.852; p=0.045) and extensive work experience (AOR: 1.479; 95%CI: 1.009–2.169; p=0.007) correlated with increased recognition of IPV-related mental health disorders. Conversely, in health centres, government ownership (AOR: 3.526; 95%CI: 1.082–11.489; p=0.037) and having a mental health resource person (AOR: 3.251; 95%CI: 1.184–8.932; p=0.036) were correlated with increased recognition of IPV-related mental health disorders. | One limitation was that the understanding of IPV-related mental disorders among nurses and midwives was gauged by asking participants to select disorders from a provided list, which may not fully capture their awareness. The assessment of screening tool availability relied on written responses, lacking physical verification. Important factors like coordination and supervision in mental health services were not explored, potentially impacting IPV-related mental healthcare delivery. Participants' responses may have been influenced by social desirability, posing a limitation. |

|

Baker and Showalter (2018)65 Country: US Setting(s): Did not specify aside from women's health settings SU |

To understand smoking among women in rural Central Appalachia. |

Qualitative. Content analysis. |

Purposive sample. Rural nurses: n=15 |

Semi-structured small focus group and individual interviews. | The study identified the themes: reasons for smoking, reasons for quitting, barriers to quitting, and perceptions of current interventions. It emphasized the significant influence of the rural social setting on smoking habits, including the presence of smokers in social networks and mixed attitudes toward smoking risks. Recognizing this strong social influence is crucial for effective women's health promotion in the area. | The most notable study limit is the purposive sample. While efforts were made to select nurses from various counties and age groups, the study's university setting might have led to a bias in participant selection, potentially resulting in higher-than-average education levels among the nurses sampled. |

|

Beks, et al (2018)10 Country: Australia Setting(s): EDs and urgent care centres MHSU |

To explore the experience of rural nurses in managing acute mental health presentations within an emergency context. |

Qualitative. Inductive descriptive approach with principles of naturalistic inquiry. |

Purposive sample. Rural generalist nurses: n=13 | One-page demographic questionnaire; semi-structured interviews. | The study identified four key themes: 'we are the frontline', 'doing our best to provide care', 'complexities of navigating the system', and 'thinking about change'. Rural generalist nurses primarily deliver care to mental health consumers in EDs and urgent care centres. Limited support is provided from local mental health clinicians and emergency service providers, often resorting to telephone triage after hours. Additional challenges include coordinating patient transfers to inpatient facilities and feeling inadequately supported. Regardless, nurses strive to deliver the best possible care, in spite of reporting skill and knowledge deficits. | The sample composition depended on nurses' responses to the study invitation, potentially overlooking novice nurses. Their inclusion could have provided valuable insights into assessing the efficacy of undergraduate mental health training for rural generalist practice readiness. |

|

Burch and Stoeckel (2021)29 Country: US Setting(s): Schools MHSU |

To explore the challenges rural school nurses face in Colorado. |

Qualitative. Descriptive phenomenological study. |

Purposive sample. Rural school nurses: n=9. |

Semi-structured interviews. | Three themes were identified: (1) rural school nurses' efforts to meet students' extensive physical and mental health issues, (2) school nurses struggle to help rural students in extreme poverty, and (3) communication challenges experienced by rural school nurses. | Study limitations included a small, homogeneous sample from a limited, high-poverty area. Future research should involve qualitative studies exploring rural school nurses' roles and potential contributions, gathering perspectives from educators, school board members, and administrators. |

|

Cole and Bondy (2020)50 Country: Canada Setting(s): Nurse setting not specified MH |

To explore rural clinicians' understanding of farmers' mental health and wellbeing, current health services, and potential responses. |

Qualitative. Content analysis. |

Purposive and snowball. Rural mental health nurses: n=4 (and family physicians: n=5). |

Semi-structured interviews. | This study included three main themes: (1) farming as a unique subculture, (2) farming involved both benefits and challenges for health, and (3) farmers rarely seek care. | This study had a small sample size and its findings may not be applicable to other farmers in different regions. |

|

Cosgrave, et al (2018)4 Country: Australia Setting(s): Community mental health MH |

To identify work challenges negatively affecting the job satisfaction of early-career CMH professionals working in rural Australia. |

Qualitative. Grounded theory approach. |

Purposive. Rural community mental health workers: n=25. Of this sample, rural registered nurses: n=6. |

Semi-structured interviews. | The study revealed that factors diminishing job satisfaction among early-career rural-based CMH professionals also impact all rural CMH professionals, with greater impact in more remote areas. Early-career professionals facing rural health challenges alongside sector-specific constraints experience compounded negative effects on job satisfaction. This likely contributes to the high levels of dissatisfaction and turnover among Australia's rural-based early-career CMH professionals. | Recall bias may affect the career reflections of health professionals who work in CMH for 5 years, compared to their first few years. This limitation was particularly notable for RA4 (remote regions) participants; hence the inclusion criteria were relaxed for the RA4 participants. |

|

Cree, et al (2021)5 Country: US Setting(s): EDs MH |

To understand factors associated with whether US EDs had a pediatric mental healthcare policy. |

Quantitative. Cross-sectional survey analysis. |

Purposive. Nurse managers reported whether their hospitals had a policy to care for children with social/mental health concerns (n=3612). |

Analyzed data from the National Pediatric Readiness Project, a nationally representative cross-sectional survey of US EDs. | Overall, pediatric mental health policies were in 46.2% of EDs. Urban areas had a pediatric mental health policy more often than remote (PR: 0.4; 95%CI: 0.3–0.5), rural (PR, 0.7; CI: 0.6–0.7), and suburban (PR: 0.7; 95%CI: 0.6–0.8) areas. | The ED ability to provide mental health care may not be captured by the presence of a pediatric mental health policy. The survey questions lacked depth. ED policies may have changed since 2013. The study's cross-sectional design limits causal or directional understanding. ED managers may misreport the presence of ED policies. |

|

Crowther and Ragusa (2014)16 Country: Australia Setting(s): Community mental health MHSU |

To explore the effects of mental policy changes and the curtailment of mental health nursing education on the realities of working as a mental health nurse in rural and remote locations in New South Wales, Australia. |

Qualitative. Grounded theory approach. |

Purposive. Rural or remote mental health nurses: n=32. |

Focus groups: n=5. | Findings indicated feelings of nostalgia and remorse about former (compared to current) mental health nursing. Nurses longed for past mental health hospital work and were uncertain about whether their knowledge and skills were sufficient for today's mental health nursing environment. | No limitations section. Scoping review authors noted that there was no demographic information included and this study was conducted in one region of Australia so may not reflect the experiences of nurses from other regions in Australia or worldwide. |

|

De Kock and Pillay (2016)56 Country: South Africa Setting(s): Primary health care centres MH |

To fill knowledge gaps with regard to mental health nurse human resources in South Africa's PRPHC settings. |

Quantitative. Descriptive quantitative analysis. |

Data from 98% of South African PRPHCs: n=160. | Primary and secondary data analysis looking at mental health nurse human resources in PRPHCs. | The findings suggest a distressing shortage of mental health nurses in South Africa's rural public areas. Only 62 (38.7%) of the 160 facilities employ mental health nurses, a total of 116 mental health nurses. They serve an estimated population of more than 17 million people, suggesting that mental health nurses are employed at a rate of 0.68 per 100 000 population in South Africa's PRPHC areas. | Even though the findings could be interpreted as representative because 98% of the sample's facilities participated in the audit, the results should be regarded as a guide for further, comprehensive enquiries. With the time elapsed since the start of the audit, the authors, while making every effort to maximise the inclusivity of facilities, cannot claim that an exhaustive list of health facilities was included because some facilities may have been added or removed by provincial departments. This limiting factor, together with the rural population's calculation that was based on primary and secondary data collection, suggests a tentative interpretation of findings. |

|

De Kock and Pillay (2018)57 Country: South Africa Setting(s): Primary health care centres MH |

To provide a situation analysis of South Africa's PRPHC mental health human resources and services. |

Quantitative. Situation analysis. |

Data from 160 (98.3%) of South African rural PRPHC facilities. | Primary and secondary data analysis looking at mental health human resources in rural primary health facilities, mental health nurses, clinical psychologists, mental health medical doctors and psychiatrists. | Results indicate the following clinicians work in rural primary healthcare settings at rates per 100 000 people: mental health nurses (0.68), clinical psychologists (0.47), mental health medial doctors (0.37), and psychiatrists (0.03). The following percentages of facilities do not have these clinicians employed or features: psychiatrists (96%), mental health medical doctors (81%), clinical psychologists (64%), mental health nurses (61%), specialist mental health outreach services (69%), and mental health multidisciplinary teams (78%). | Despite auditing 160 health facilities (98%), the lack of clear provincial and national PRPHC documentation may have resulted in institution omissions. The absence of recent official records suggests caution in interpreting the population relying on these facilities, even though the calculation used primary and secondary sources. |

|

Dube and Uys (2015)31 Country: South Africa Setting(s): Primary healthcare clinics MHSU |

To determine the practices of primary healthcare nurses in the management of psychiatric patients in primary healthcare clinics in one of the rural districts in South Africa. |

Mixed methods. Quantitative: Descriptive analysis. Qualitative: Thematic analysis. |

Purposive. Rural professional nurses: n=32. Rural staff nurses: n=15. |

Quantitative: Questionnaire to determine psychiatric nursing practice. Qualitative: Semi-structured interviews with primary care nurses. Review of patient records. |

The findings indicated that in 83.3% of the sites, treatments were not reviewed semi-annually; there were no local psychiatric emergency drug administration protocols; and psychiatric patients did not receive medication education at any of the study sites. | Patient satisfaction with the service was not evaluated at any of the study sites. |

|

Etter, et al (2019)58 Country: Canada Setting(s): Indigenous community MHSU |

To describe a community-specific and culturally coherent approach to youth mental health services in a small and remote northern Indigenous community in Canada's Northwest Territories, under the framework of ACCESS Open Minds, a pan-Canadian youth mental health research and evaluation network. |

Qualitative. Community mapping design. |

Ulukhaktok, Northwest Territories youth mental health services. | Community mapping. | The local team in Ulukhaktok identified gaps in youth programming and mental wellness services through community mapping. | No limitations section. This study was conducted in one Northwest Territories region in Canada, and its process or findings may not be applicable to other regions or communities. |

|

Gaffey, et al (2016)54 Country: Ireland Setting(s): Hospital and community mental health MH |

To assess current knowledge and attitudes of Irish mental health professionals to the concept of recovery from mental illness. |

Quantitative. Descriptive survey design with content analysis of open-ended questions. |

Entire rural mental health practitioner population. Rural mental health practitioners: n=176. Of these, rural nurses: n=118. |

Descriptive survey: the Recovery Knowledge Inventory. | When comparing recovery scores to Cleary and Dowling (2009)†, or comparing recovery scores to levels of experience, no significant differences were discovered. Improved recovery scores were associated with working in dual settings, training, and being a non-nurse. Training emerged as the strongest predictor of better recovery knowledge. | The study was conducted in 2013, so the recovery knowledge and attitudes may have changed between that date and the study publication date. Additionally, there are likely other factors in explaining knowledge and attitudes toward recovery not considered in the regression model. Further, to prevent participant recognition from their quotes, qualitative analysis was conducted without pairing the quotes with demographic information, and thus prevented different demographic categories from being compared. Finally, since data were collected through self-reporting questionnaires, the potential for reporting bias exists. |

|

Gohar, et al (2020)43 Country: Canada Setting(s): Hospital and long-term care facilities MH |

To identify and understand the factors associated with sickness absence among nurses and personal support workers through several experiences while investigating if there are northern-related reasons to explain the high rates of sickness absence. |

Qualitative descriptive. Inductive thematic analysis. |

Purposive. Rural (northern) nurses (registered nurses (n=6) and registered practical nurses (n=4)), personal support workers (n=5), and key informants (n=5). |

Focus groups. | Four themes included occupational/organizational challenges, physical health, emotional toll on mental wellbeing, and northern-related challenges. Staffing shortages were a key factor that led to sickness absences. | Since this is a qualitative study, its findings may not be transferable to other regions, although other northern regions may face similar challenges. Biases may have been introduced by using thematic analysis. Not all informants could attend the focus groups, so their perspectives may have been missed. |

|

Happell, et al (2012)32 Country: Australia Setting(s): Community mental health MH |

To identify the activities that nurses in community mental health services undertake. |

Qualitative. Thematic analysis. |

Purposive. Rural mental health nurses (n=38) from community (n=11), acute inpatient (n=17), or both (n=2) settings. |

Semi-structured focus groups. | The main themes include stigma of mental illness, barriers to accessing physical healthcare services, nurse adaptations under demands, and community and integration toward better overall health. | No limitations section. Scoping review authors note that this study is from one region of rural Australia; thus the findings may not be transferability to other rural regions globally. |

|

Jacob, et al (2022)44 Country: Australia Setting(s): EDs MHSU |

To explore and understand rural ED nurses' views on the daily experience and impact of violence, and its perpetrators. |

Qualitative. Phenomenology. |

Purposive. Rural ED nurses (n=14). |

Semi-structured focus groups. | Violence was ongoing and significantly affected rural ED nurses. The nurses anticipated, tolerated, and had to manage violence in the workplace. | The qualitative results may have limited generalizability. |

|

Jahner, et al (2020)27 Country: Canada Setting(s): Acute care, primary care, community health, home care, hospice/ palliative/end-of-life care, long-term care, mental health, other (eg nursing station, obstetrics, education) MHSU |

To explore the distressing experiences encountered by rural/remote nurses and their perception of organizational support. |

Qualitative. Descriptive survey with thematic analysis of open-ended questions. |

Purposive. Rural and remote nurses in total survey: n=3822. Subsample of nurses: n=1222 for question 1 and n=804 for question 2. |

Thematic analyses conducted on open-ended data from a pan-Canadian survey of nurses in rural and remote practice. | The three major themes related to rural and remote nurses experiences of distressing events were involvement in profound events of death/dying, traumatic injury, and loss; experiencing or witnessing severe violence and/or aggression; and failure to rescue or protect patients or clients. The three major themes relating to organizational support included feeling well supported in the work setting with debriefing and reliance on informal peer support; lack of acknowledgment and support from leaders on the nature and impact of distressing events; and barriers influencing access to adequate mental health services in rural and remote practice settings. | Since data were collected by written responses, the depth of responses may have been limited, compared to data collection by interviews. |

|

Jahner, et al (2022)45 Country: Canada Setting(s): Acute care hospitals MHSU |

To explore how registered nurses in rural practice deal with psychologically traumatic events when living and working in the same rural community over time. |

Qualitative. Constructivist grounded theory. |

Purposive and theoretical. Rural registered nurses: n=19. |

Semi-structured interviews. | Participants experienced many trauma-related events and were mainly worried about these events impacting them lifelong. Participants coped by staying strong (ie being supported by others, finding internal strength, trying to let go of the past, and by being transformed over time), and this helped participants to weather future traumatic events. | The sample did not include nurses who previously left the job or were on stress/medical leave related to traumatic events. The small sample size limits the results transferability. Nurses may have been triggered by talking about or processing traumatic events, although participants were informed of this risk beforehand, and provided with support resources. Results may not be transferable to rural nurses who are not part of the community they serve, as this study explored rural nursing practice of nurses who were integrated within their communities. |

|

Jansson and Graneheim (2018)24 Country: Sweden Setting(s): Community mental health MH |

To describe nurses' experiences of assessing suicide risk in specialised mental health outpatient care in rural areas in Sweden. |

Qualitative. Descriptive design; qualitative content analysis using an inductive approach. |

Purposive sample. Enrolled nurses: n=4. Registered nurses: n=8. |

Semi-structured individual interviews. | The results indicated that the nurses experienced distress stemming from a sense of powerlessness. They voiced feelings of doubt and isolation, grappling with ethical issues and organizational challenges. | Participants were chosen by colleagues, and interviewers had dual roles. The participant group uniformity presents a possible limitation. Nurses with less than 1 year of experience in assessing suicidality were omitted, yet their insights could have been valuable for a comprehensive understanding. |

|

Jones and Quinn (2021)33 Country: Canada Setting(s): Indigenous community SU |

To describe a buprenorphine–naloxone induction in the North. |

Qualitative. Case report. |

Rural nurse involvement is described. | Narrative case report. | Case report about a female patient aged 50 years with opioid-use disorder in a remote community. The article reviews this patient's treatment options and access along with healthcare provider collaboration. | No limitations section. Scoping review authors note that this is one case report and thus its transferability is limited. |

|

Kadar, et al (2020)17 Country: Indonesia Setting(s): Community mental health MH |

To examine the practice of mental health staff delivering mental health programs in community centres in one sub-district area in Indonesia; the majority (88.5%) of staff surveyed were rural nurses. |

Quantitative. Audit to evaluate the current practice of mental health staff. |

Purposive sample. Rural nurses: n=23. Physiotherapists: n=1. Midwives: n=2. |

Surveys. The questionnaires were adapted from Mental Health Law No. 18 and Community Mental Health Nursing Program. | While the majority of healthcare personnel adhered to governmental directives regarding mental health services, such as offering health education, early detection, counseling, monitoring pasung (physical restraint) practice, medication compliance, and rehabilitation programs, this study did not delve into the specifics of their actions. It is possible that staff members lacked adequate knowledge and skills in mental health care. None of the staff had undergone formal mental health training, and there were no comprehensive guidelines for their guidance. Moreover, community health centres faced constraints including limited staffing, funding, and facilities. | No limitations section. Scoping review authors noted that this study did not specify information about the role of the rural nurses compared to the other healthcare staff. Healthcare workers from one region were included in the study; including healthcare workers from across the country would be more inclusive. |

|

Kenny and Allenby (2013)25 Country: Australia Setting(s): Hospitals MH |

To examine issues that rural nurses face in the provision of psychosocial care in Victoria, Australia. |

Qualitative. Interpretive descriptive design with data analysis based on Attride-Stirling's (2001) approach to thematic analysis.¶ |

Snowball sampling; information was distributed through a chief nurse network, which then held information sessions to recruit study participants. Rural nurses: n=22. |

Four focus groups: two with six participants and two with five. | Five main themes were identified: constructive relationships, professional isolation, multiskilling expectations, client interaction, and competing demands. The reality that rural nurses face for psychosocial care provision is reflected in the overarching theme of 'Managing multiple roles, demands and relationships'. | The study findings may not be transferable to other regions or the larger nursing workforce. |

|

Keugoung, et al (2013)52 Country: Cameroon Setting(s): Primary care MHSU |

To describe the characteristics of suicide and assess the capacity of health services at the district level in Cameroon to deliver quality mental health care. |

Mixed methods. Qualitative: analysis method not described. Quantitative descriptive. |

Purposive. Rural nurses: n=15. |

Documentary review of medical archives, semi-structured interviews of relatives of suicide completers, focus groups of health committee members, and a survey of nurses. | A minority of the nurses (2/15) were able to name three or more depression symptoms and had awareness that depression is a risk for suicide. None of the nurses had any specific mental health training or supervision. | No limitations section. Scoping review authors note that the sample size is small and this study is limited to one rural region of Cameroon, thus it may not be generalizable or transferable to other areas or true of other nurse populations. |

|

Kidd, et al (2012)26 Country: Australia Setting(s): EDs MHSU |

To explore the experiences of general nurses working in rural hospital settings, with regards to their ED responsibilities; part of the exploration included mental health practice. |

Mixed methods. Two-stage approach. First stage: quantitative descriptive. Second stage: qualitative thematic analysis. |

Questionnaire: Purposive sampling. Rural ED nurses: n=53 Focus groups: Convenience sampling. Rural ED nurses: n=17. |

First stage: Questionnaires (including five-point Likert scales and open-ended fields). Second stage: two focus groups, framed directly from the questionnaire results. | The study found that nurses lacked confidence due to the irregular nature of their work and the diverse cases they encountered, leading to 'skills rusting'. They felt the need for diverse specialization but lacked confidence, especially in mental health, due to isolation and inadequate training. Although there are good emergency training programs for rural nurses, access is limited due to various constraints. | No limitations section. Scoping review authors noted that this study was conducted within one rural region and may not be transferable to rural nurses in other regions. |

|

Lamba and Aswani (2012)47 Country: Saint Kitts and Nevis Setting(s): Hospital and community health clinics MHSU |

To describe the burden of psychiatric disease and mental health services available on the Caribbean island of Nevis. |

Qualitative. Case study. |

Hospital and clinic records, unpublished psychiatric case information, and experience of primary health care providers: n=2. | Hospital and clinic record and report analysis, unpublished information pertaining to psychiatric case analysis, and personal experience of primary healthcare providers integrated in the analysis. | The island of Nevis' mental health services are free, and include a psychiatrist and two psychiatric nurses (twice per week, from Saint Kitts) and local primary care providers (emergency, urgent, and inpatient care). Depression, schizophrenia, and drug-induced psychosis were the most prevalent presentations. | Records to identify epidemiological and census data were of limited availability. |

|

Link, et al (2019)64 Country: US Setting(s): Hospital MH |

To survey perinatal nurses' self-efficacy in postpartum depression teaching, self-esteem, stigma and attitudes toward seeking help for mental illness. |

Quantitative. Cross-sectional, descriptive, correlational study. |

Convenience. Rural perinatal hospital nurses: n=38. |

Self-report survey. | The results found that perinatal nurses' postpartum depression teaching behaviors correlated to postpartum depression teaching self-efficacy related to postpartum, supervisor social persuasion, prior teaching mastery, and vicarious experiences of observing peers teach about postpartum depression. | This study was limited by the small convenience sample, and thus the findings may not be generalizable. There may have been a significant difference in study response rate between perinatal nurses who did and did not respond to the survey. |

|

MacLeod, et al (2022)7 Country: Canada Setting(s): Acute care, primary care, community health, long-term care, home care, hospice/end-of-life/palliative care, mental health, other (not specified); multiple practice settings MHSU |

To explore the characteristics and context of practice of registered nurses, licensed practical nurses, and registered psychiatric nurses in rural and remote Canada, who provide care to those experiencing mental health concerns. |

Quantitative. Cross-sectional survey that included open-ended questions. Descriptive analysis. |

Systematically stratified target sample. Regulated nurses in rural and remote areas: n=3822. |

Nursing Practice in Rural and Remote Canada pan-Canadian cross-sectional survey; included 24-item Job Resources in Nursing Scale and the 22-item Job Demands in Nursing Scale. | Only a small percentage of nurses (9.8%) were mental health-only nurses, and those nurses were mostly registered psychiatric nurses. For nurses for whom mental health was one part of their practice ('mental health-plus'), they typically worked in both hospital and primary care settings as generalists. Both mental health-only and mental health-plus nurses experienced moderate levels of job resources and demands. Over half of the nurses faced violence recently, especially licensed practical nurses. Nurses frequently commented on the difficulties in accessing specialized mental health services predominantly in Indigenous communities or remote regions. | The main limitations stem from the national survey's cross-sectional design, its broad scope, and the limited number of mental health-related variables in the original survey tool. This analysis might have underestimated the proportion of rural and remote nurses delivering mental health care, as they may not have categorized mental health as a distinct area of practice. |

|

McCullough, et al (2012)28 Country: Australia Setting(s): Remote areas, community health MHSU |

To identify and describe hazards within the remote area nurse workplace from the perspective of experienced remote area nurses. |

Qualitative. The Delphi method. |

Purposive sample. Expert remote area nurses: n=10. Panel nomination was based on extended length of practice as a remote area nurse, geographical representation and active involvement in the remote area nurse community. |

The Delphi method: three rounds of questionnaires that are progressively refined knowledge and opinion with the aim to reach consensus from participants. | This study shows that remote area nurses face diverse hazards from various sources, with environmental hazards complicated by their remote living and practice locations. Complex community relationships, lack of experience, and organizational support contribute to increased violence risk. 'Major' or 'extreme' risks include clinic maintenance and security, patient care at staff residences, remote area nurse inexperience, intoxicated clients with mental health issues, and a work culture tolerating verbal abuse. Management inaction and inadequate recognition of violence risks by employers are also significant hazards. | Bias may exist in the Delphi study panel selection. |

|

Mendenhall, et al (2018)34 Country: Kenya Setting(s): Primary care MHSU |

To investigate nurses' perceptions of mental healthcare delivery within primary-care settings in Kenya. |

Qualitative. Thematic analysis. |

Convenience. Nurses from three hospitals: public urban (n=20), private urban (n=20), and public rural (n=20). |

Semi-structured interviews. | Nurses considered mental health services a priority and thought that integrating them into primary care could shield them from competing health concerns, financial obstacles, stigma, and social issues. While many nurses deemed this integration acceptable and viable, limited provider knowledge, particularly in rural regions, and a scarcity of specialists, posed barriers. | Since this is a qualitative, cross-sectional design, there may be limited transferability about task-sharing in Kenya in general. |

|

Mpheng, et al (2022)41 Country: South Africa Setting(s): Community health MH |

To explore and describe the views of healthcare practitioners on the aspects that hinder providing comprehensive care for MHCUs, the role players needed to execute comprehensive care and what can be done to improve comprehensive care for MHCUs in the community setting in one of the subdistricts of the North West Province, South Africa. |

Qualitative. Qualitative descriptive design. |

Purposive. Rural nurses (n=19) and medical doctor (n=1). |

Semi-structured interviews. | Four major themes were healthcare practitioners' understanding of comprehensive care to MHCUs, barriers to comprehensive care to MHCUs, stakeholders needed for providing comprehensive care to MHCUs, and suggestions for comprehensive care improvement to MHCUs. | The aim was to involve all members of the multidisciplinary team in the study, but not all members (ie psychologists, social workers, psychiatrists, and other mental healthcare professionals) were available due to COVID-19 restrictions. Consequently, data collection only involved hospital-based members (ie professional nurses and one medical doctor). This situation posed a challenge, leading the researcher to revise the data collection method from focus group interviews to individual interviews conducted over the phone. |

|

Nankivell, et al (2013)59 Country: Australia Setting(s): Hospital and community mental health MH |

To explore nurses' views and perceptions to identify (1) orientation of nurses to human rights, and (2) access of consumers with serious mental illness to GP services. |

Qualitative. Thematic analysis. |

Purposive. Nurses from regional and rural settings: n=38. |

Focus groups. | The study highlighted notable issues regarding service users' access to physical health care. Nurses seldom broached the topic of human rights, and when they did,it wasn't seen as a strategy to improve access to much-needed physical healthcare services for consumers with serious mental illness. Two main factors contributing to poor access to physical healthcare services were identified: clinical and attitudinal barriers. | Scoping review authors noted that this study is from one region in Australia and thus its findings may not be transferable to other regions globally. |

|

Pattison-Sharp, et al (2017)53 Country: US Setting(s): Schools SU |

To (1) describe the context within which school nurses encounter student opioid prescriptions, (2) assess school nurses' preferences for training and student education, and (3) explore urban–rural differences in school nurses' experiences and training preferences. |

Quantitative. Quantitative descriptive. Qualitative thematic analysis of open-ended questions. |

Convenience. School nurses: urban (n=371) and rural (n=251). |

Online cross-sectional survey design with closed and open-ended questions. | A significant portion of school nurses (40.3%) had come across students with opioid prescriptions, yet only a small percentage (3.6%) had naloxone available for potential overdoses. A majority of school nurses (69.9%), particularly those in rural areas, believed students would benefit from opioid education (74.9% v 66.6%, p=0.03). Additionally, most school nurses (83.9%) expressed interest in receiving training related to opioids. | The authors couldn't determine the exact number of school nurses who received the survey, so the true response rate remains unknown. Therefore, it is unclear how representative the survey results are for the Carolinas or other states. This lack of data could pose a risk of selection bias. Moreover, coding bias may have been introduced from only one coder who reviewed all qualitative responses. |

|

Peritogiannis, et al (2022)48 Country: Greece Setting(s): MMHUs MH |

To explore the differences among two MMHUs, one being run by a university general hospital (MMHU UHA) and the other being run by a non-governmental organization (MMHU I-T). |

Quantitative. Two-tailed z-test for independent proportions and t-test for independent samples. |

Purposive. Compared rural MMHUs in Greece, which employ rural mental health nurses: n=7. |

Chart review of patient information from two rural MMHUs. | Staffing composition differences were found between MMHU UHA (more medical and nursing staff), and MMHU I-T (more psychologists, social workers and health visitors). For MMHU I-T, patients were significantly older than MMHU UHA patients (mean age 64.5 v 55.3 years) with more elderly patients receiving treatment (56.5% v 20%). Both MMHUs provided home-based care to a similar proportion of patients. For MMHU UHA, a significantly higher percentage of patients with schizophrenia attended, whereas significantly more patients with affective disorders, anxiety disorders and organic brain disorders attended the MMHU I-T. | The study results could inform clinical practice in rural areas; the findings may not generalize to other rural regions in Greece. Variations in resources and staffing levels among different MMHUs, including those in public hospitals and those run by NGOs, may affect the applicability of the findings. Additionally, certain aspects of care, such as patient symptoms and hospitalizations, were not addressed in this study. |

|

Ratter (2023)42 Country: Scotland Setting(s): Schools MH |

To explore the experiences and perceptions of a small school nursing team of the support they receive to deliver emotional and mental health interventions. |

Qualitative. Thematic analysis. |

Rural or remote school nurses: n=4. | Questionnaire and semi-structured interviews. | Peer support was seen as a key facilitator and training was also considered crucial, but time constraints hindered both. Limited access to support services for children and youth, coupled with a lack of recognition and understanding of participants' roles by others, added to the challenges of delivering emotional and mental health interventions. | The limited sample size restricted the diversity of ages, experiences, and perspectives, thereby limiting the transferability of the findings and the ability to draw conclusions. Although all participants were women, this reflects the composition of the school nursing workforce. |

|

Rieckmann, et al (2016)63 Country: US Setting(s): Substance abuse programs MHSU |

To study American Indian and Alaska Native substance abuse treatment provider and program characteristics between urban and rural communities. |

Quantitative. Cross-sectional survey design. Multivariate regression. |

Stratified sample. Clinical administrators and other senior clinical staff from substance abuse treatment programs serving American Indian and Alaska Native communities: n=192. |

Online or telephone survey. | Rural programs were less likely to have nurses, traditional healing consultants, or ceremonial providers on staff, consult external evaluators, use strategic planning for program quality improvement, offer pharmacotherapies, pipe ceremonies, or cultural activities. They were also less likely to participate in research or program evaluation studies but more likely to employ elders as traditional healers, offer AA-open group recovery services, and collect data on treatment outcomes. Greater receptivity to evidence-based treatments was associated with larger clinical staff, presence of addiction providers, directors perceiving a gap in evidence-based treatment access, and collaboration with stakeholders to improve service access. However, programs providing early intervention services showed lower openness. | This study heavily depended on the reports of program staff, which may not fully represent the insights and experiences of all staff members. Programs that didn't participate could differ from those included. Cross-sectional non-experimental studies like this one lack the ability to analyze changes over time or factors influencing program, staff, and service delivery beyond association. |

|

Searby and Burr (2021)60 Country: Australia Setting(s): Did not link the setting type to the rural nurse's data MHSU |

To explore the perspective of alcohol and other drug nurses about telehealth during COVID-19, including rural nurses. |

Qualitative description. Thematic analysis. |

Purposive sample with maximum variation. Alcohol and other drug nurses: n=19. |

Semi-structured interviews. | Study participants faced hurdles in transitioning to telehealth methods. Overcoming challenges such as perceived loss of therapeutic communication, assessing risks like domestic violence, and addressing the needs of marginalized consumer groups is crucial for telehealth to succeed in alcohol and other drug treatment. Nevertheless, telehealth proved to be a beneficial addition to current practices for nurses serving consumers in regional or remote areas, or for those who preferred this mode of service delivery. | The sampling method used in this study resulted in a large number of participants from New South Wales, Australia, with no representation from other Australian states and territories. While workforce data indicate that most Australian nurses in alcohol and other drug settings are in New South Wales, the lack of representation and subjective nature of participants' experiences mean the findings may not represent all alcohol and other drug nurses across Australia. Similarly, despite efforts to recruit from New Zealand, only one participant was from there, possibly due to poor engagement with professional organizations or ongoing COVID-related lockdowns. |

|

Singh, et al (2015)55 Country: Australia Setting(s): Mental health MH |

To investigate the extent to which mental health nurses employed within rural and metropolitan areas of Australia are affected by burnout. |

Quantitative. Cluster-sampling, cross-sectional study. |

Representative sample of the population framework. Rural and urban nurses: n=319. |

Survey: The Maslach and Jackson Burnout Inventory and a demographic questionnaire. The inventory has 22 items designed to assess three aspects of the burnout syndrome: emotional exhaustion, depersonalisation and personal accomplishment. |

This study's findings show that mental health nurses in both urban and rural Australia experience burnout. Lately, job dissatisfaction due to work stress has been rising among rural nurses. | The findings are limited to mental health nurses in the four Australian states studied. Caution is advised in interpreting the results without a longitudinal study. Additionally, the use of self-report measures may pose limitations due to potential social desirability bias and self-disclosure concerns. |

|

Stanisławska, et al (2015)40 Country: Poland Setting(s): Primary health care centres SU |

To show the problem of alcoholism in a rural area and the role of a family nurse. |

Quantitative. Non-parametric c2 test. |

Purposive. Rural family nurses: n=50. Rural care recipients: n=100. |

Questionnaire with open, semi-open, and closed questions. | In the rural areas, men consumed alcohol more frequently than women. Most villagers understood alcoholism, knew how to assist addicted individuals, and were familiar with the concept of codependency. Family nurses in these areas took steps to promote health and address alcohol-related issues among their patients. They collaborated with other primary healthcare team members to ensure comprehensive care was provided. | No limitations section. Scoping review authors noted that it was unclear what questions were asked and whether the questions gave sufficient depth to understand the nurse's role in prevention, assessment, and treatment of alcohol use disorder. |

|

Stryker, et al (2022)35 Country: Guatemala Setting(s): Primary care MH |

To describe the experience of primary care nurses treating depression in rural Guatemala. |

Mixed methods. Quantitative survey: descriptive statistics. Qualitative focus groups: thematic analysis. |

Purposive. Survey of rural nurses: n=22. Focus groups of rural nurses: n=16. |

Cross-sectional survey with closed- and open-ended questions and focus groups. | Guatemalan primary care nurses described culturally contextual depression symptoms, community-related socioeconomic factors contributing to depression, and treatment preferences. Challenges in connecting patients to mental health care were noted due to limited referral options and privacy concerns. Nurses stressed the importance of community education on depression and the need for additional mental health resources to enhance their ability to identify and treat depression. | To maintain confidentiality, this study did not link survey responses to individuals or clinical locations. While responses were generally consistent, the design limited understanding regional differences' impact on the explanatory model of disease in Guatemala. Data collection occurred during two staff meetings, potentially missing perspectives of absent nursing staff. The study did not employ a validated burnout screening tool, and cross-cultural validation has not been done in Guatemala. Instead, a screening questionnaire was developed with input from bicultural Wuqu' Kawoq staff members. The insights provided by nurses working for a private non-profit may not be generalized or transferred to those in Guatemala's public health system. |

|

Sutarsa, et al (2021)61 Country: Australia Setting(s): N/A MH |

To understand whether there are spatial inequities of mental health nurses in rural and remote Australia |

Quantitative. Cross-sectional analysis of spatial distribution of mental health nurses per 100 000 people. |

Purposive. The National Health Workforce dataset including Local Government Areas: n=544. |

Analysis of the publicly available 2017 National Health Workforce dataset. | This study illustrates the disparity in mental health nurse distribution between urban and rural/remote areas. | No limitations section. Scoping review authors noted that this study may not reflect spatial inequities of other rural regions worldwide. |

|

Trop, et al (2018)66 Country: Mongolia Setting(s): Clinic or hospital MHSU |

To explore healthcare providers' perspectives on postpartum depression in Mongolia. |

Qualitative. Content analysis. |

Purposive. Healthcare providers that work with urban and rural clients (n=15); included nurse-midwives (n=5), and a family clinic nurse (n=1). |

Semi-structured interviews and focus groups. | Most providers acknowledged some basic knowledge of postpartum depression but had limited experience with postpartum depression patients. They primarily described signs and symptoms based on their own observations rather than patient reports. Providers generally viewed postpartum depression as a complex condition influenced by obstetric, psychological, socioeconomic, and cultural factors. Traditional concepts of postpartum depression, such as sav khuurukh, were commonly cited. While providers had varied opinions on where women seek help for postpartum depression, they generally agreed that patient–provider discussions are crucial for identification. However, such discussions are rare due to providers' lack of confidence, training, time constraints, and other barriers. | The data were gathered from a small sample of providers in Ulaanbaatar, limiting transferability to other regions or countries. Research on rural providers' perspectives is warranted. Qualitative methodology limitations, such as group dynamics and social desirability biases, may have influenced responses. Focus groups comprised homogeneous groups of providers, with separate interviews for those with unique views. Different administrators led discussions, potentially affecting participant responses and inter-rater reliability. |

|

van Rooyen, et al (2019)62 Country: South Africa Setting(s): Primary healthcare facilities MH |

To explore and describe experiences of persons living with severe and persistent mental illness and those of their families in rural South Africa. |

Qualitative. Descriptive, exploratory design. |

Convenience sampling to select the healthcare facilities and purposive to recruit participants. Persons living with severe and persistent mental illness (n=18) and family members (n=11). |

Unstructured interviews. | Two main themes included primary healthcare access challenges and the inadequate mental healthcare provision. | Originally, the plan was to conduct unstructured individual interviews at the homes of individuals living with severe and persistent mental illness and their families. However, some potential participants' homes in deep rural areas were inaccessible due to lack of roads. As a result, the study was limited to accessible rural areas, potentially missing certain viewpoints from eligible participants. |

|

Wand, et al (2021)39 Country: Australia Setting(s): EDs MHSU |

To explore mental health liaison nurses' experiences of working in the EDs of two rural Australian settings. |

Qualitative. Thematic analysis. |

Purposive. Rural mental health liaison nurses: n=12. |

Semi-structured interviews. | Participants highlighted several advantages of integrating mental health liaison nurses within the ED team. They also acknowledged some challenges related to changing thinking and practice and offered suggestions for enhancing mental healthcare in the ED. | This evaluation only included two rural emergency settings and may not reflect the broader rural context. Further investigation is needed to determine the model's broader applicability, as its key principles and governance may not be suitable for all EDs. |

|

Whiteing, et al (2021)36 Country: Australia Setting(s): Hospital, remote practice setting, community, multiple sites, other MHSU |

To delineate the practice of rural and remote nurses in Australia. |

Qualitative. Multiple case study design. |

Purposive. Rural and remote nursing documents (n=42), rural nurses: online questionnaire (n=75) and interviews (n=20). |

Content analyses of nursing documents and online questionnaires, and semi-structured interviews. | The major themes included 'a medley of preparation for rural and remote work'; 'being held accountable'; 'alone, with or without someone'; and 'spiralling well-being'. Despite various strategies, challenges such as isolation, stress, burnout, and organizational commitment persist for rural and remote nurses. Professional development courses and graduate certificates, while beneficial, have yet to alleviate these issues. | Being qualitative research, the findings of this study may not apply to other regions in Australia or abroad. Participants were recruited through communication via Executive Directors of Nursing, but the researcher was unsure if all registered nurses or only some facilities were contacted, potentially introducing bias. The code of conduct for nurses replaced several documents examined in phase I, and the effectiveness of the new code, focusing more on nurses' cultural practices, was not evaluated in this study, suggesting a need for future research. Another limitation is the lack of perspectives from different stakeholders, such as students, other nurses, and managers, which could be addressed in future research. |

|

Wideman, et al (2020)46 Country: US Setting(s): Maternal child health home visits MHSU |

To explore how family and community characteristics affected rural nurse home visiting. |

Qualitative. Case file review. |

Purposive. Rural families: n=433. Member checking with rural nurses: n=3. |

Content analysis of rural nurse home visitation files supplemented by quantitative descriptions of the study counties and member checking. | While concerns of the families served, such as mental health, may not be specific to rural areas, challenges in accessing resources and meeting various needs were distinct. Nurses adjusted engagement and service strategies accordingly. | The study relied solely on nurse case notes, which may vary in content, potentially impacting the coding process and the emergence of themes. Interviewing families or using validated diagnostic instruments could have provided additional insights into mental health disorders or substance abuse, but these were not employed. The study was conducted in three counties, limiting the transferability of the findings, as rural demographics can differ significantly. Additionally, the data are nearly a decade old, which may affect their relevance. |

|

Wilson and Usher (2015)51 Country: Australia Setting(s): N/A MH |

To understand new ways that young rural people with mental health problems could be helped at an early point in their mental health decline. |

Mixed methods. Phase one: Quantitative; survey design descriptive, comparative; content analysis. Phase two:Qualitative; no design specified; thematic analysis. |