Introduction

Courage can be an integral part of clinical practice, yet it is not well described in the literature, nor is it often recognised and supported in practice1-3. Our recent qualitative studies have explored the underlying attributes of clinical courage among rural doctors practising in resource-limited settings. These doctors often work at the limits of their scope of practice to provide the medical care that is required by their community4,5. From the lived experiences of these doctors, we initially described underlying attributes of clinical courage. These attributes include a strong sense of belonging to and seeking to serve their community, accepting clinical uncertainty and persistently seeking to prepare for clinical challenges, working deliberately to understand and marshal resources, humbly seeking to know the limits of their own clinical practice, needing to clear a cognitive hurdle when deciding to act, and gaining collegial support to continue their roles4,5. Our understanding of these features was strengthened by a subsequent study exploring rural doctors’ experiences in the early phases of the COVID-19 pandemic6.

Using the attributes identified from these qualitative studies, we recently developed and tested a questionnaire to further examine clinical courage among rural doctors7. The initial questionnaire included four to six items for each of the attributes of clinical courage4. Psychometric bifactor modelling identified that 18 of these items could be categorised into seven group factors and two correlated latent bifactors or concepts: ‘functioning within the health service context’ and ‘responsiveness to community’ (Table 1). ‘Functioning within the health service context’ contributes to clinical courage and to the group factors of teamwork, critical preparation, collegial support, and humble self-reflection. ‘Responsiveness to community’ contributes to clinical courage and to the group factors of serving the community, self-consciously acting in response to need, and mutual trust. The present article builds on psychometric testing of the 18-item survey to explore whether the clinical courage questionnaire measures a unique concept, how it relates to other existing psychometric concepts, and how clinical courage concepts are related to individual demographic and clinical practice characteristics.

Methods

Survey instrument

Table 1 shows the 18 questionnaire items contributing to the concepts ‘functioning within the health service context’ (items 1–11) and ‘responsiveness to community’ (items 12–18). These items were scored by participants using a 10-point Likert scale, where 1 was described as ‘not at all like me’ and 10 as ‘very much like me’. The survey also collected the following demographic details: age, gender, rural background, and the WONCA geographical region8. Survey items related to clinical experience were the type of clinical practice (general practice, rural generalist, specialist, other rural doctor), years in clinical practice, years in rural practice, and level of health service resources available (from 1 = ‘very poorly’ to 10 = ‘extremely well resourced’). Doctors’ likelihood of remaining in rural practice was reported using a scale from 1 (‘highly likely to leave’) to 10 (‘definitely remain’).

Table 1: The 18-item clinical courage questionnaire relating to the concepts ‘functioning within the health service context’ and ‘responsiveness to community’

| In my current clinical practice, how like me is it ... [response Likert scale 1–10] | ||

|---|---|---|

| Concept | Questionnaire item | Group factor |

| Functioning within the health service context | 1. To draw on the team to develop flexible alternate plans when resources are limited | Teamwork |

| 2. To make tricky clinical decisions together with other members of the clinical team | ||

| 3. To be aware of and check the equipment available to me | Critical preparation | |

| 4. To reflect on my performance when I have done something outside of my comfort zone | ||

| 5. To expand my knowledge and skills by reflecting carefully on patient outcomes | ||

| 6. To rely on clear thinking and a systematic approach to the basics in difficult situations | ||

| 7. To have supportive colleagues who keep me working at the edge of my comfort zone | Collegial support | |

| 8. To be supported to return to do something again when I lose confidence in my ability | ||

| 9. To seek support from my colleagues to persist with working at the edge of my scope of practice | ||

| 10. To seek out discussions with rural colleagues to better judge my competence | Humble self-reflection | |

| 11. To seek feedback from rural colleagues about my performance when I have a poor patient outcome | ||

| Responsiveness to community | 12. To take responsibility for the health outcomes of my community | Serve community |

| 13. To increase my scope of practice to meet the needs of my community | ||

| 14. To act when my patient needs help urgently and I am the only one available | Self-consciously act | |

| 15. To make a decision in an emergency that may potentially be wrong, rather than to make no decision | ||

| 16. To provide support to colleagues to continue with the ambiguities of practice | ||

| 17. To have a deep connection to my rural community | Mutual trust | |

| 18. To trust the community to support me | ||

Psychometric scales for testing divergent validity

In addition to the clinical courage questionnaire, the survey included five additional psychometric scales to enable a divergent validity assessment. To reduce the demand on participants, each was asked to complete only one of the validation scales from the following:

- Professional Fulfilment Index (PFI), an 18-item instrument to assess doctors’ professional fulfilment and burnout9.

- KCES-R scale, a revised version of the Kiersma–Chen Empathy Scale (KCES) originally developed to assess health professional students’ empathy (global and personal). The scale comprises seven items related to global healthcare professional empathy ratings and seven items related to self-perceived empathy ratings10,11.

- Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K10), a 10-item scale to identify clinically significant psychological distress, with two second-order factors for anxiety and depression12. Based on the factorial composition of the K10, we chose to examine anxiety and depression separately.

- New General Self-Efficacy Scale (NGSE), an eight-item scale developed to measure individuals' perception of their ability to perform across a variety of different situations13.

- Personal Wellbeing Index (PWI), comprising seven domains corresponding to standard of living, health, achieving in life, relationships, safety, community connectedness, and future security, and representing the first level of deconstruction of the global question ‘How satisfied are you with your life as a whole?’14.

The PFI, NGSE, and PWI scales were included because of potential positive relationships between these constructs and the attributes of clinical courage. Other constructs considered to be unrelated or negatively related to clinical courage were for burnout (built into the fulfilment scale) and a major issue for medical workers, and the K10 as a measure of depression and anxiety. These scales were chosen to help define the space in which clinical courage operates.

Recruitment

Information about the study and a link to the online survey (SurveyMonkey) was distributed through the electronic email lists of rural doctors’ associations in Australia (Australian College of Rural and Remote Medicine), Canada (Society of Rural Physicians of Canada), and internationally via Rural WONCA. Also, the study was promoted on the closed Facebook site ‘Rural anaesthesia down under’ (Australia). As the number of email and Facebook recipients was unknown, the response rate is undetermined. All participants provided their consent online prior to accessing the survey. Survey participants were asked to opt in to complete a re-test survey after 2–4 weeks to allow for a reliability assessment.

Outcome measures

Scores for clinical courage concepts

The score for ‘functioning within the health service context’ was calculated as the mean score of items 1–11. Likewise, ‘responsiveness to community’ was calculated as the mean score of items 12–18. (Table 1).

Independent variables

The independent variables examined in relation to ‘functioning within the health service context’ and ‘responsiveness to community’ scores were gender (male, female), age group (20–29, 30–39, 40–49, 50–59, 60–69, 70–79 years), geographical region (three groups), rural background, years lived rurally/in clinical practice/in rural clinical practice (1–4, 5–9, 10–19, 20–29, 30–39, ≥40 years), type of clinical practice (four groups), and level of available health service resources categorised as poor (1–3), minimal (4–5), adequate (6–7), good–excellent (8–10).

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were undertaken in the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences v28 (IBM Corp; https://www.ibm.com/products/spss-statistics) or STATA v17.0 (StataCorp; https://www.stata.com). Descriptive survey results are reported as means (±SD), frequencies, and proportions. Tests for associations were conducted using Pearson correlations for continuous variables and analysis of variance (ANOVA) to compare scores across groups. Bonferroni post-hoc tests were conducted for pairwise comparisons.

Ethics approval

The project was approved by the University of Adelaide Human Research Ethics Committee (approval number H-2022-086).

Results

In total, 337 online surveys were collected and 81 were subsequently excluded due to the level of missing data (>10%), leaving 256 cases as the group for analysis. A re-test survey was completed by 116 doctors at 2–4 weeks after the initial survey.

Participant characteristics

Region working in

Over 60% (n=164) were from the Asia-Pacific region, particularly from Australia (n=101) (Table 2). A further 19.5% (n=50) were from North America, mostly from Canada (n=38). Small numbers of responses (n=36) were collected from other regions, including European countries (n=24).

Gender and age

The sample included 116 (45.3%) females, 130 (50.8%) males, and 10 people of unspecified gender (3.9%). The mean age was 50.7±12.0 years with over 90% of doctors aged between 30 and 70 years (Table 2). The distribution of gender across age group showed a significant difference, with larger numbers of women under 40 years and larger numbers of men over 50 years (χ2=14.51, df=5, p<0.05).

Rural experience and clinical practice characteristics

All respondents were currently working rurally (a screening question). Most (86.3%) reported they currently lived in a rural community and around half (49.2%) described themselves as having a rural background. The mean years lived rurally was 17.5±11.9 years. Most doctors were rural generalists (n=159) or practising general practice/family medicine (n=68).

The mean duration of clinical experience was 23.3±13.0 years and clinical time in rural settings was 18.8±11.6 years. Seventy-two percent of doctors had 10 or more years of rural/remote clinical experience (Table 2). Overall, 55.1% of doctors reported at least 80% of their clinical practice in rural/remote locations and 26.2% of doctors had completed all their clinical practice rurally/remotely (data not shown). About one third (31.6%) scored their level of health service resources as ≤5 on a scale from 1 = ‘very poorly’ to 10 = ‘extremely well resourced’, with no responses at either extreme. A breakdown of demographic profiles by geographical region is available in Supplementary table 1. Canadian doctors were slightly younger, with fewer years lived/ clinical experience in rural. ‘Other’ doctors were more likely to report a rural background.

Table 2: Participant demographics, rural/remote and clinical practice experience

| Variable | n† | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Region | |||

| Asia-Pacific (incl. Australia and New Zealand) | 164 | 64.1 | |

| North American | 50 | 19.5 | |

| Other¶ | 36 | 14.1 | |

| Gender§ | |||

| Male | 130 | 50.8 | |

| Female | 116 | 45.3 | |

| Age (years) | |||

| 20–29 | 4 | 1.6 | |

| 30–39 | 53 | 20.7 | |

| 40–49 | 62 | 24.2 | |

| 50–59 | 62 | 24.2 | |

| 60–69 | 57 | 22.3 | |

| ≥70 | 12 | 4.7 | |

| Currently live rurally | |||

| No | 33 | 12.9 | |

| Yes | 221 | 86.3 | |

| Rural background | |||

| No | 124 | 48.4 | |

| Yes | 126 | 49.2 | |

| Time lived in rural or remote area (years) | |||

| 1–4 | 26 | 10.2 | |

| 5–9 | 49 | 19.1 | |

| 10–19 | 71 | 27.7 | |

| 20–29 | 7 | 2.7 | |

| ≥30 | 55 | 21.5 | |

| Type of clinical practice | |||

| General practice/family medicine | 68 | 26.6 | |

| Other rural doctor | 12 | 4.7 | |

| Rural generalist | 159 | 62.1 | |

| Specialist | 10 | 3.9 | |

| Duration of rural/remote clinical experience (years)‡ | |||

| 1–4 | 17 | 6.6 | |

| 5–9 | 48 | 18.8 | |

| 10–19 | 76 | 29.7 | |

| 20–29 | 46 | 18.0 | |

| ≥30 | 63 | 24.6 | |

† Total sample = 256. Frequencies and percentages do not sum to 100% because of the small percentage of missing data for each variable (not shown).

¶ Includes European countries (n=24), South Asian countries (n=5), African countries (n=4), South American countries (n=2), East Mediterranean countries (n=1).

§ Not specified (n=10, 3.9%).

‡ Over half (55.1%) of doctors had ≥80% of their clinical experience in rural/remote areas. Data for total years of clinical experience not shown.

Clinical courage concept scores

The sample mean scores for ‘functioning within the health service context’ and ‘responsiveness to community’ were 8.27±1.19 and 8.23±1.21, respectively. For each of the questionnaire items, the sample mean scores were at the higher end of the scales (Supplementary table 2). The highest scores were for the items (It is like me …) ‘To reflect on my performance when I have done something outside of my comfort zone’ (mean score=9.07±1.29) and ‘To act when my patient needs help urgently and I am the only one available’ (mean score=9.41±1.29). Lowest mean scores were observed for the three ‘collegial support’ items (Supplementary table 2). The mean scores for ‘functioning within the health service context’ did not vary significantly across the three regional groups (F2,247 =0.01, p=0.987). Similarly, the mean score for ‘responsiveness to community’ was not associated with geographical region (F2,247 =0.05, p=0.955). This suggests that these cohorts were relatively homogeneous in their responses.

Composite and re-test reliability

Composite reliability (ω) was calculated with adjustment for the bifactor modelling. The estimates for the two bifactors were ‘functioning in the health service context’ (ω=0.88, very acceptable) and ‘responsiveness to community’ (ω=0.59, marginally acceptable). Test–re-test reliability was examined using data collected 2–4 weeks apart (n=116) and showed strong correlations for the repeated scores for both ‘functioning within the health service context’ (r=0.82, p<0.001) and ‘responsiveness to community’ (r=0.77, p<0.001). Overall, the test–re-test reliability was solid and supportive of the stability of the clinical courage concepts.

Relationships between clinical courage concepts and other psychometric scales

The results of correlation tests with five other psychometric scales are shown in Table 3. There were moderate, significant correlations between the scores for clinical courage concepts and scores for the PFI, PWI, KCES-R Personal, and the NGSE. No significant correlations were observed for the PFI burnout scale, the KCES-R (global empathy), or the K10 depression and anxiety scores. Overall, these findings indicate that clinical courage does not duplicate other related constructs but occupies its own space. The pattern of correlations with scales measuring positive constructs but not with negative suggests clinical courage is a positive construct.

Table 3: Clinical courage concept scores and correlation analysis with other psychometric scales

| Clinical courage concept measure | n | Mean score (SD) | Possible range | Pearson correlation coefficient (r) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Functioning in the health service context | Responsiveness to community | |||||

| Functioning in the health service context | 256 | 8.27 (1.19) | 0–10 | – | – | |

| Responsiveness to community | 256 | 8.23 (1.21) | 0–10 | – | – | |

| Psychometric scales | ||||||

| PFI Fulfilment | 67 | 3.80 (0.63) | 1–4 | 0.36** | 0.42*** | |

| PFI Burnout | 63 | 2.42 (0.75) | 1–4 | 0.08 | 0.02 | |

| PWI | 62 | 7.76 (1.37) | 1–10 | 0.34** | 0.28* | |

| KCES-R Global | 25 | 5.19 (0.59) | 1–7 | 0.10 | 0.07 | |

| KCES-R Personal | 33 | 5.54 (0.66) | 1–7 | 0.38* | 0.43* | |

| NGSE | 55 | 4.03 (0.55) | 1–5 | 0.35** | 0.45*** | |

| K10 Depression | 23 | 2.04 (0.89) | 1–5 | –0.08 | –0.07 | |

| K10 Anxiety | 23 | 2.02 (0.68) | 1–5 | 0.03 | 0.02 | |

*p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001

K10, Kessler Psychological Distress Scale. KCES-R, Kiersma–Chen Empathy Scale. NGSE, New General Self-Efficacy Scale. PFI, Professional Fulfilment Inventory. PWI, Personal Wellbeing Index. SD, standard deviation.

Associations with demographics

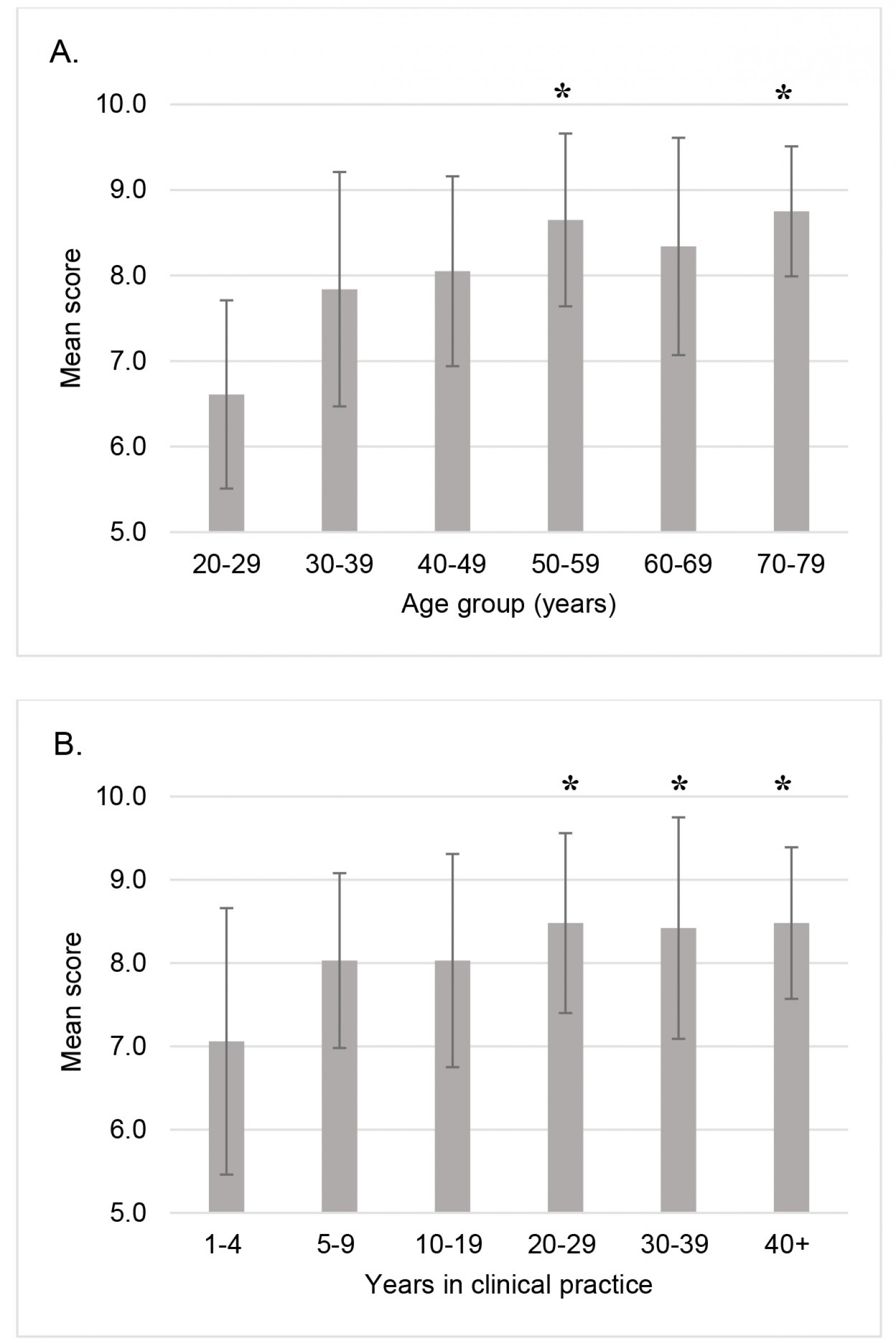

The ‘functioning within the health service context’ score was not associated with any demographic characteristics, including age, years of rural clinical experience, type of clinical practice (GP, rural generalist, or specialist) or level of resources (Table 4). ‘Responsiveness to community’ scores were associated with age, in addition to currently living in a rural community, years lived rurally, years in clinical practice, and years of rural experience (Table 4). Figure 1 shows that ‘responsiveness to community’ scores increased with increasing age and years of experience.

Table 4: Associations between ‘functioning within the health service context’ and ‘responsiveness to community’ scores and participant demographics, rural location, and clinical experience

| Variable | Functioning in the health service context | Responsiveness to community | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | df | F | df | ||

|

Age group (20–29, 30–39, 40–49, 50–59, 60–69, 70–79 years) |

0.65 | 5,244 | 5.11*** | 5,244 | |

| Gender (male/female) | 0.55 | 1,244 | 0.06 | 1,244 | |

| Live rurally (yes/no) | 0.19 | 1,252 | 3.97* | 1,252 | |

|

Years lived rurally/remotely (1–4, 5–9, 10–19, 20–29, 30–39, ≥40 years) |

1.50 | 5,202 | 2.97* | 5,202 | |

| Rural background (yes/no) | 0.51 | 1,248 | 1.43 | 1,248 | |

|

Years in clinical practice (1–4, 5–9, 10–19, 20–29, 30–39, ≥40 years) |

1.61 | 5,243 | 3.57** | 5,243 | |

|

Years of rural clinical experience (1–4, 5–9, 10–19, 20–29, 30–39, ≥40 years) |

1.67 | 5,244 | 2.52* | 5,244 | |

|

Type of clinical practice (general practice/family medicine, other rural doctor, rural generalist, specialist) |

2.11 | 3,245 | 1.34 | 3,245 | |

|

Level of resources available (poor (1–3), minimal (4–5), adequate (6–7), good–excellent (8–10)) |

1.26 | 3,237 | 1.49 | 3,237 | |

*p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001

df, degrees of freedom. F, F-statistic from one-way analysis of variance.

Figure 1: Mean ‘responsiveness to community’ scores according to (A) age group and (B) years in clinical practice.

Figure 1: Mean ‘responsiveness to community’ scores according to (A) age group and (B) years in clinical practice.

Associations with doctors’ intentions to remain in rural practice

Doctors were asked how likely they were to remain in rural/remote practice in the next 5 years (1 = ‘highly likely to leave’ to 10 = ‘highly likely to remain’). The mean score was 6.87±3.24 and there was a weak positive correlation with scores for ‘functioning within the health service context’ (r=0.23, p<0.001) and ‘responsiveness to community’ (r=0.14, p=0.02).

Discussion

This was an international study involving rural doctors from diverse regions. The scores for clinical courage concepts were high across the regions, suggesting these concepts capture important features of rural practice. To date, urban physicians have not been studied, so it is not possible to comment on whether or not clinical courage is a consistent feature in urban practice. We expect there may be differences between rural and urban doctors for the ‘responsiveness to community’ concept as connectedness with rural communities is well documented in the rural medical literature15.

When compared with other psychometric constructs, we found only moderate overlap between clinical courage concepts with those that looked at positive attributes (self-efficacy, personal empathy, fulfilment, wellbeing) and that there was no overlap with scales that looked at negative attributes (burnout, anxiety, and depression). This confirmed that our clinical courage questionnaire was testing for a different overall concept than other potentially related constructs. These findings also contribute to our understanding of clinical courage. The moderate relationship with self-efficacy, the belief in one’s ability to act13, is consistent with clinical courage being active. Personal empathy is the ability to feel and understand another’s experience11 and is expected to be a necessary element of clinical courage. Acting with courage may contribute to a sense of fulfilment from work and individual wellbeing.

The results of this study show that physicians who are older, who live rurally, and have been in (rural) practice for a longer time have higher scores for ‘responsiveness to community’. At this stage, we have not examined the independent effects of age and years in practice. However, as identified by Walters et al, relationships with colleagues, patients and communities are important for clinical courage5. A longer time in rural practice allows for the development and strengthening of these important community relationships. We found no associations between ‘functioning within the health service context’ scores and demographic or practice characteristics. This suggests that teamwork, preparedness, and reflective practice are fundamental to these rural physicians, regardless of experience.

Scores for ‘functioning within the health service context’ and ‘responsiveness to community’ showed weak positive correlation with a measure of doctors’ likelihood of remaining in rural/remote practice. This understanding suggests retention strategies need to focus on both strengthening professional development and collegiality in a rural site and the profession more generally, as well as supporting doctors and their families to embed themselves within their rural community.

The clinical courage questionnaire incorporated all of the attributes identified in our qualitative studies, except for clearing the cognitive hurdle when faced with unfamiliar clinical challenges4. Initial questionnaire items designed to examine this attribute did not correlate or load as expected. This is possibly because there is no common language among physicians to describe these circumstances. At this stage, the research team is continuing to explore how to include this attribute in the questionnaire. Future work will also examine the clinical courage concepts in rural and metropolitan doctors.

Limitations

This international sample of rural doctors is not representative of countries around the world. However, given the commonality and level of education of the participants, the regional differences are likely to be much smaller than in the corresponding general populations. Our findings show interesting associations between clinical courage concepts and length and future intentions of rural practice, but these should be interpreted cautiously as this is the first survey to implement the clinical courage questionnaire, and the sample size is modest considering the diversity of the target population. Finally, we remind readers that associations are useful at a population level and an individual clinical courage questionnaire score cannot be utilised to predict the individual’s level of clinical courage or their future interest in rural practice.

Conclusion

The clinical courage questionnaire is shown to measure a unique construct and to be reliable in a sample of international rural doctors. Both clinical courage concepts, ‘responsiveness to community’ and ‘functioning within the health service context’, are related to future intentions of rural practice.

Funding

Australian Rural Clinical Schools are funded through the Australian Government Rural Health Multidisciplinary Training grant scheme.

Conflicts of interest

JK, IC, DC, and LW have all worked as rural doctors and have leadership roles in rural medical undergraduate or vocational training.