Introduction

Supplement use is common among menopausal women across a wide range of countries1. The prevalence of supplement use has been shown to increase with age in samples of women in the US, Australia, and Canada2-4. Two-thirds of US women over the age of 40 years utilize at least one supplement, and 80.2% of women aged over 60 years take one or more supplements2. This widespread use could reflect unmet medical needs or a preference for therapies perceived to be more natural5,6. Supplements are also commonly marketed to perimenopausal and menopausal women as a means of reversing aging and easing climacteric symptoms7,8. Because vitamin deficiencies are associated with adverse outcomes, supplements may offer some benefit for the subset of individuals with known deficiencies or strict dietary restrictions9,10. However, there is insufficient evidence to conclude that routine use of supplements is beneficial for primary prevention of disease in the general population11-16. Currently, the regulation of supplements varies significantly by country17. Australia, Canada, and Japan conduct pre-market approvals or regulations for supplements. In contrast, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) does not regulate dietary supplements for safety or efficacy, potentially increasing the risk of adverse events or substandard product quality18-20. Recent investigations of supplements in the US identified problematic product labeling and contamination with FDA-prohibited ingredients20,21. Even without robust safety and quality regulations, a significant portion of US residents continue to use supplements and often underreport this use to clinicians22.

Hawaiʻi Island is the largest island in the Hawaiian Archipelago, but this rural landmass is home to only 15% of the state’s total population23. The geographic isolation, growing senior population, and significant physician shortage create unique challenges to healthcare provision in this rural setting24. Further, Hawaiʻi is demographically distinct from other countries, and even from regions within the US. Compared to continental US population, Hawaiʻi residents include a larger proportion of people who are Asian, Native Hawaiian, Pacific Islander, or multiple races (45.4% v 6.7%)23. Specifically, a larger proportion of Hawaiʻi residents identify with Japanese, Chinese, or Filipino heritage than residents in many other regions of the US. While it is known that supplement use varies due to geographic, cultural, and ethnic factors, supplement use among perimenopausal and menopausal women in Hawaiʻi Island has yet to be characterized25,26. This study aimed to measure the prevalence of supplement use among a uniquely diverse population of perimenopausal and menopausal women in a rural region of Hawaiʻi. Secondary objectives included assessing motivations for taking supplements, the financial cost of purchasing supplements, common side effects, and sources of supplement-related information.

Methods

Ethics approval

The Hawaiʻi Pacific Health Research Institute reviewed this study’s protocol and determined this study to be exempt from institutional review board review.

Study sample

From May to August 2023, participants were recruited for this cross-sectional study using printed flyers in an academically affiliated women’s health clinic in Hilo, an unincorporated settlement on Eastern Hawaiʻi Island. This island is coextensive with Hawaiʻi County. Consisting of 98.7% rural land, Hawaiiʻi County is the most rural county in the state. Additionally, the majority of this island’s residents live in a rural setting27. The generalist obstetrician-gynecologists in this office provide full-spectrum women’s health care, including preventive health visits and annual well-woman assessments consistent with the recommendations of the Women’s Preventive Services Initiative28. These clinicians routinely care for patients who travel more than 50 miles (~80 km) to see a women’s health professional. This office accepts both public and private insurance. Patients interested in participating had the choice of reviewing a printed or mobile version of the study information sheet, followed by a short screening for inclusion and exclusion criteria. Patients were eligible to participate if they were aged at least 40 years and assigned female at birth. Exclusion criteria included being unable to complete the survey in English and being pregnant at the time of the survey.

Data collection

Participants who met inclusion criteria completed either a printed or web-based survey. This 10-minute survey collected information on demographic characteristics and supplement use. Because one in four residents of Hawaiʻi are multiracial, participants were given the option to select multiple races and ethnicities. Participants who reported having at least one menstrual period in the previous year were classified as perimenopausal. Participants who reported their last menstrual period occurred more than 1 year previous to study participation were classified as menopausal. Supplements were defined based on the established criteria of the U.S. Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act of 1994 (DSHEA)29. A previously validated tool to assess dietary supplement use was adapted for this study (Supplementary table I)30. The original survey tool presented a list of dietary supplements, sports drinks, and meal-replacement products. This tool was modified to remove the questions concerning sports drinks/gels and meal-replacement products, because these items are not considered dietary supplements under the current DSHEA29. Additionally, trends concerning sports drinks and meal replacements were outside the scope of the current study, and collecting this additional data would have significantly extended the survey duration, potentially impacting survey completion rates. The survey instrument was also modified to include 22 additional supplements that are either commonly marketed for menopausal symptoms or traditionally used by Native Hawaiian, other Pacific Islander, and East Asian cultures (Table 1). Women who endorsed using one or more supplements were then asked to identify the supplement, record the frequency of use, and provide a free-text response explaining their reasoning for taking the supplement. Consistent with the original survey tool, this survey also included a short-answer prompt asking participants to estimate the monthly cost of their supplements. Multiple-choice questions were used to collect data concerning the prevalence of specific side effects and sources of supplement-related information. Participants were compensated with a bottled refreshment.

Table 1: Supplements added to a revised survey tool characterizing supplement use among perimenopausal and menopausal women in a rural region of Hawaiʻi, USA

|

Supplement |

Description |

|

′Awa or kava |

Product of plant Piper methysticum; used in many Pacific Island cultures31-33 |

|

′Awapuhi |

Perennial root herb Zingiber zerumbet; used in many Pacific Island cultures33,34 |

|

Bioastin (Hawaiian astaxanthin) |

Pigment found in red-colored marine organisms; believed to have anti-aging properties35 |

|

Black cohosh |

North American herb Actaea racemosa; believed to provide relief from menopause-related symptoms36 |

|

Chaulmoogra |

Semi-deciduous tree Hydnocarpus wightianus; brought to Hawai′i as a treatment for Hansen’s disease32 |

|

Chinese yam |

Dioscorea polystachya; used in traditional Chinese medicine; believed to have estrogen-like properties37 |

|

Diindolylmethane |

Crucifer-derived phytochemical; believed to play a role in estrogen metabolism38 |

|

Dong quai |

Root of Angelica sinensis; used in Chinese medicine, including for treatment of vasomotor symptoms of menopause36 |

|

Evening primrose seed oil |

Oil from North American wildflower Oenothera biennis; believed to relieve symptoms of menopause36 |

|

Green tea |

Tea made from Camellia sinensis; believed to improve menopause-related symptoms39 |

|

Kalo |

Root of Colocasia esculenta; believed to have medicinal uses in Hawaiian and Pacific Island cultures31,33,40 |

|

Ko |

Varieties of sugarcane; used in Native Hawaiian healing practices31,33,41 |

|

Ko′oko′olau |

Flowering plant Bidens pilosa; found only in Hawaii; used in Native Hawaiian healing practices31,33 |

|

Koali |

Ipomoea indica; used in Native Hawaiian healing practices31,33 |

|

Kukui |

State tree of Hawai′i (Aleurites moluccanus); used in Native Hawaiian healing practices31,33,42,43 |

|

Noni |

Evergreen tree Morinda citrifolia; believed to have medicinal uses in Polynesian culture31,33,44 |

|

′Ohi′a ′Ai |

Syzygium malaccense; used in Native Hawaiian healing practices31,33 |

|

Popolo |

Solanum americanum; used in Native Hawaiian healing practices31,33,43 |

|

Red clover |

Extracts from Trifolium pratense leaf; used in Native Hawaiian healing practices36 |

|

Soy isoflavone |

Extracts are believed to reduce menopause symptoms36 |

|

Ti leaf |

Leaf of Cordyline fruticosa, which grows throughout the Pacific Islands31,33,45 |

|

′Uhualoa |

Waltheria indica; shrub indigenous to Hawai′i; used in Native Hawaiian healing practices33,43,45 |

Statistical analysis

The Statistical Package for Social Sciences v29 (IBM Corp; https://www.ibm.com/products/spss-statistics) was used for the statistical analysis. Descriptive statistics were used to describe the resulting data, including the prevalence of supplement use, supplement-related side effects, and sources of supplement-related information. The mean was calculated for the self-reported cost of supplements. A backwards elimination regression (F≥0.1) was used to assess whether demographic characteristics (including age, BMI, race, and ethnicity), time since last menstrual period, participant confidence in supplements, and participant perception of health predicted two outcomes: polysupplement use (defined as using four or more supplements in the past 6 months) and the average monthly cost of supplements.

Results

During the 3-month recruitment period, 106 individuals were screened. Three screened individuals were not eligible due to being pregnant (n=2) or under the age of 40 years (n=1). Three of the eligible individuals did not return the survey, resulting in 100 responses in the final analysis. During the recruitment period, this clinic cared for 515 women over the age of 40 years, resulting in an estimated recruitment rate of 21%. However, the true recruitment rate is likely higher because an unmeasured portion of the 515 women did not meet all of the inclusion criteria. Most of the respondents were married (56%) and more than 10 years beyond their last menstrual period (58%; see Table 2). Twenty-four percent of respondents identified as multiracial. Most participants identified as Asian (55%), White (41%), or Native Hawaiian (21%).

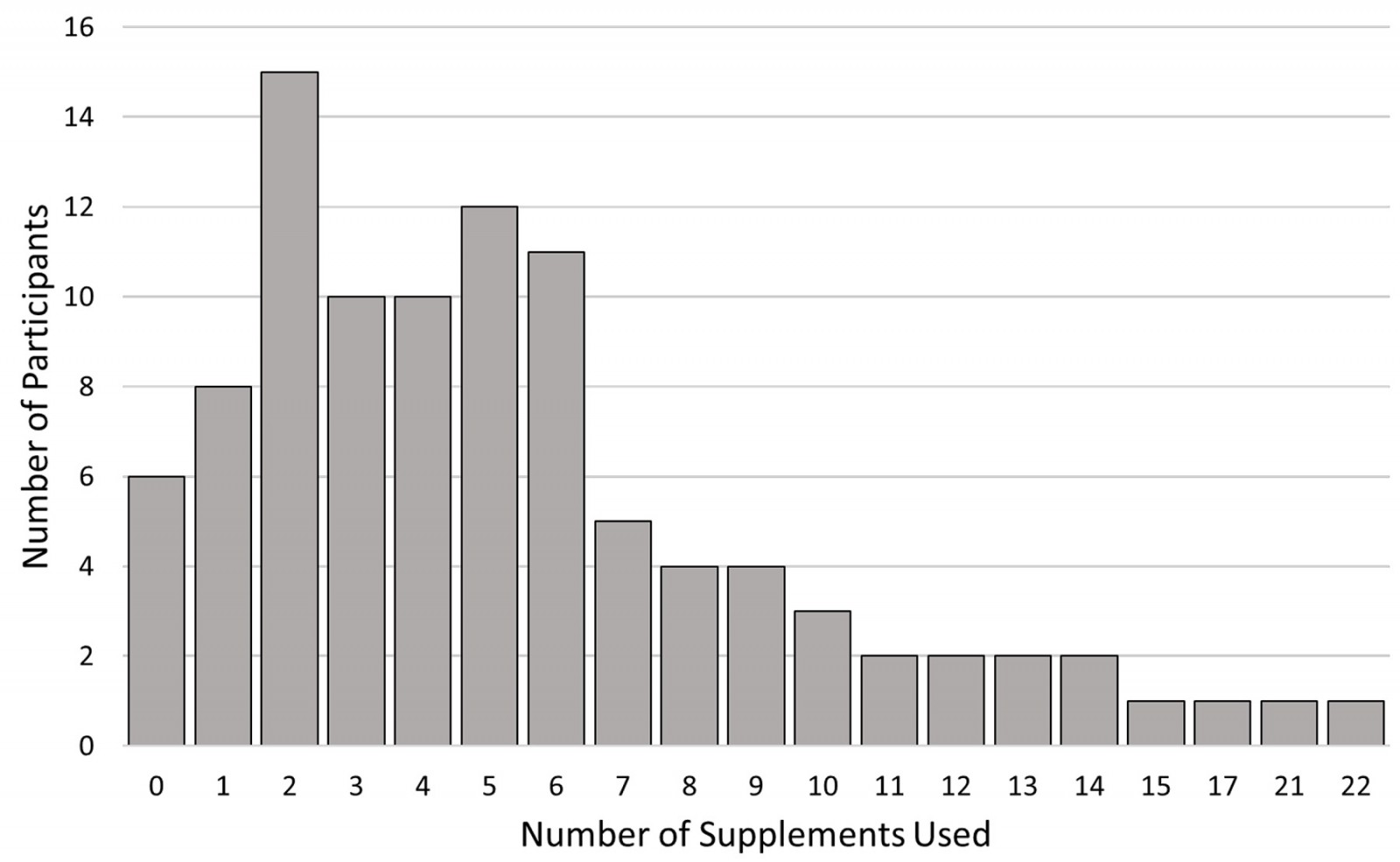

Supplement use was common in this sample, with 94% of respondents using at least one supplement in the previous 6 months (Fig1). The number of supplements ranged from 0 to 22 (mean=5.4); 60% of participants used four or more supplements, and 12% used 10 or more supplements. Fifty-eight percent of women age 40–59 years used four or more supplements, and 62% of participants aged 60 years and older used four or more supplements. The most commonly reported supplements included vitamin D (57%), calcium (52%), a multivitamin (44%), and magnesium (29%). In the regression analysis, polysupplement use was not predicted by demographic characteristics, time since last menstrual period, confidence in supplement efficacy, or one’s self-perception of health.

One-third of respondents reported experiencing one or more side effects. The most commonly reported side effect was gastrointestinal distress, including stomach pain, diarrhea, nausea, and/or vomiting (17%). Health professionals were the most commonly identified source for information regarding supplement use (69%), followed by family members (35%), friends (29%), and the internet (23%). Books, television, magazines, medical journals, and vitamin store employees were less commonly cited as sources to learn about supplements (<10%). The majority of respondents were motivated to take supplements as part of an effort to promote general health (51%) or replace dietary deficiencies (11%). A desire to ease symptoms of menopause was not a common motivator in this sample (3%). Twenty-three percent of participants did not report a reason for taking one or more supplements. Common free-text reasons for supplement use included bone health, energy, and dietary deficiency. Other respondents reported wanting to improve their immune system, sleep, skin, heart, weight, arthritis, joints, and muscle health.

The self-reported monthly cost of supplements was up to US$500 (A$759) (mean=US$55.41 (A$84.09)), and this cost was not predicted by participant demographics. The backwards elimination regression analysis revealed that participant perception of their health was the only factor to significantly predict the amount of money spent on supplements (standardized β=0.44; p=0.02).

Table 2: Demographic characteristics of participants in survey of supplement use among perimenopausal and menopausal women in a rural region of Hawaiʻi, USA (N=100)

| Demographic characteristic | Proportion of sample (%/mean±SD) | |

|---|---|---|

| Race and ethnicity† | ||

| Asian | 55 | |

| Japanese | 29 | |

| Filipina | 20 | |

| Chinese | 13 | |

| Okinawan | 4 | |

| Korean | 1 | |

| Caucasian/White | 41 | |

| Native Hawaiian | 21 | |

| Hispanic | 10 | |

| American Indian and Alaska Native | 5 | |

| Other Pacific Islander | 3 | |

| African American/Black | 2 | |

| Marital status | ||

| Single | 17 | |

| Married | 56 | |

| Widowed | 13 | |

| Separated/divorced | 14 | |

| Time since most recent menstrual period (at time of survey) (years) | ||

| <1 | 19 | |

| 1–5 | 11 | |

| 5–10 | 11 | |

| >10 | 58 | |

| Education | ||

| Some high school | 4 | |

| High school graduate | 10 | |

| Some college courses | 22 | |

| Undergraduate degree (Associate’s or Bachelor’s) | 39 | |

| Graduate degree (Master’s or Doctorate) | 24 | |

| Age (years) | 62.7±11.7 | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27.4±6.1 | |

Figure 1: Total supplements used in the previous 6 months by participants in survey characterizing supplement use among perimenopausal and menopausal women in a rural region of Hawaiʻi, USA

Figure 1: Total supplements used in the previous 6 months by participants in survey characterizing supplement use among perimenopausal and menopausal women in a rural region of Hawaiʻi, USA

Discussion

Supplement use is very common in perimenopausal and menopausal women in a rural setting in the state of Hawaiʻi. Interestingly, the prevalences of any supplement use and multi-supplement use were higher than those noted in previous studies of similarly aged women in the continental US, the UK, China and Canada2,4,46-48. The prevalence of polysupplement use (using four or more supplements) in the current study was two to five times higher than the reported prevalence for similarly aged adults2. Only 6% of respondents did not use supplements.

The reason for this high prevalence of supplement use is likely multifactorial. For example, cultural influences impact the acceptability of supplement use25,26,48. Additionally, rural Hawaiʻi faces a significant shortage of osteopathic medical providers, potentially leading many residents to turn to over-the-counter supplements for their healthcare needs. Naturopathic healers also serve as primary care providers for many women on Hawaiʻi Island, and may contribute to this study’s high rate of patients identifying healthcare providers as their sources for supplement information compared to previous studies49,50.

The cost of supplements varied considerably within this study’s sample. Participants who reported being in better health also reported spending more on supplements. However, it remains unclear whether individuals who feel healthy are more likely to financially prioritize supplements or if spending a large amount of money on supplements makes people feel better about their health. Although this study did not collect data on income, the mean annual supplement cost among study participants was approximately 1% of the mean household income for Hawaiʻi Island51. This monetary burden of supplement use is not isolated to this study’s population. Within the US, the supplement industry’s annual sales exceed US$20 billion (~A$30 billion) and continue to grow52. Future research should explore the impact of supplement costs on rural families, especially those in areas with high cost of living such as Hawaiʻi.

Half of participants reported taking supplements to improve their general health, while only a small proportion used supplements to address an acute issue or deficiency. This finding is consistent with previous studies of perimenopausal and menopausal women in other regions, where a desire to improve one’s overall wellbeing was a common motivator47,53. While some supplements likely offer benefits for certain patients, such as those with restrictive diets or diagnosed deficiencies, there is insufficient data to conclude that supplements improve overall health for most people11-16. Additionally, with contamination rates ranging from 12% to 60% for US supplements, the chance of exposure to a potentially harmful contaminant increases with each additional supplement20,50. For countries with more robust supplement regulations (such as Australia, Canada, and Japan), concerns about exposure to harmful contaminants are minimized but the risk of adverse reactions due to polysupplement interactions remains. In this study, gastrointestinal distress was the most commonly reported supplement-related side effect. Adverse effects from supplements should be considered in the differential diagnosis for all patients with unexplained gastrointestinal symptoms, but especially for patients taking multiple supplements or residing in countries without stringent safety regulations for supplement production.

Limitations of this study include the small sample size and recruitment from a single clinic. Additionally, sample bias may be present because this study was unable to sample women not presenting for medical care. However, because supplements are available to the studied population without a prescription, these products may be similarly or even more common among uninsured populations54-56. Another limitation includes an inability to stratify patients based on rurality of their residence. ZIP code data were not collected from participants. However, because the majority of Hawaiʻi Island residents live in a rural location and there were no obstetrician-gynecologists practicing on East Hawaiʻi Island outside of Hilo at the time of the survey, it is reasonable to assume the survey results reflect mostly rural residents27. A major strength of this study is the inclusion of a diverse sample with populations that have been underrepresented in previous research on this topic, such as US residents of Asian race and Native Hawaiian people.

Conclusion

Supplement use in perimenopausal and menopausal women in rural Hawaiʻi Island is significantly higher than for other studied populations. Given the high prevalence of supplement use and the potential impact on patients’ lives, osteopathic clinicians in rural regions, including Hawaiʻi Island, may consider engaging in thoughtful discussions of the risks and benefits of specific supplements during preventive care visits for patients of all ages, but especially for those over the age of 40 years. Future directions should include the development and validation of decision aid tools that can assist clinicians in efficiently providing evidence-based, patient-centered counseling concerning supplement use to perimenopausal and menopausal women. The needs and healthcare practices of people living in rural communities warrant further research to ensure clinicians can adequately address their unique medical needs.