Introduction

In Canada, a significant health gap exists between Indigenous* and non-Indigenous Peoples1,2. Indigenous mothers and children face disproportionately high rates of negative health outcomes in comparison to non-Indigenous mothers and children3-5. This disparity includes higher rates of obesity, gestational diabetes, postpartum depression, sudden infant death syndrome, and mortality rates3,5,6. Colonization is a contributing factor to the existing health inequity for Indigenous mothers and their children4,5 and has impacted the determinants of health on all levels, including government policies, and personal health practices7,8.

The impact of colonization on gender is especially relevant to the maternal–child health context9. Following European gender norms, the dynamic and interactions between women and men changed and the power and traditional roles of women were stripped in many Indigenous communities9-11. Prior to first contact, Indigenous women were in leadership positions with decision-making power and viewed as equals to men9,10. Currently, Indigenous women are still affected by this dynamic, leading to marginalization in society, reduced access and poor treatment in health services, and large numbers of missing and murdered Indigenous girls and women9,12.

Maternal–child health programs are one aspect of public health that aims to reduce morbidity and mortality rates for women and children and improve their health and wellbeing13. For the purposes of this project, maternal–child health programs for Indigenous families include an action or approach aimed at one or more levels (ie individual, family, whole community, policy) to reduce the mortality rates of Indigenous women and children and improve their health and wellbeing4,13-18. Although there has been significant investment in Indigenous-specific maternal–child health programs and programs with prevalent Indigenous participation in Canada at the federal, provincial, territorial, and municipal levels, there has been little impact on health outcomes4,19. Rural and remote communities face additional challenges that inhibit program impact, including poor road conditions, lack of transportation, program unavailability, and insufficient funding, which create barriers to accessing programs20-22. The lack of impact on health outcomes suggests research is needed to determine how programs can be successfully implemented to create positive outcomes and address the burden of health inequity1,5,23.

Community input is an important feature in the success of Indigenous health programs1,24, and can be partly determined by frontline workers such as nurses, Indigenous health and community workers, midwives, counsellors, and peer support workers25-32. Frontline workers hold a valuable emic view of the environment where interventions are delivered and they possess local knowledge that can contribute to overall program success4,33. However, there is a dearth of research that describes how frontline worker knowledge and contributions have influenced the development, implementation, and evaluation of health programs4,14,34,35.

To begin addressing the current maternal–child health research gap in successful program implementation and understand frontline worker contributions in health program planning, delivery, and evaluation, a research partnership was formed with KidsFirst North in Northern Saskatchewan, Canada. Saskatchewan is a province located in central Canada, known as part of the Prairie region. Indigenous and non-Indigenous community members reside in northern Saskatchewan communities with approximately 80% of the population identifying as Indigenous36,37. KidsFirst North serves 11 northern, rural communities in this province: Beauval, Buffalo Narrows, Creighton, Cumberland House, Green Lake, Ile a la Crosse, La Loche, La Ronge, Pinehouse, Sandy Bay, and Stony Rapids38.The largest community that KidsFirst North serves is La Ronge. La Ronge has a population of approximately 2700 and is located 4 hours by road from the closest major urban centre, Saskatoon36.

KidsFirst is a voluntary, provincially funded maternal–child health program that is administered under the Ministry of Education Early Years Branch39. Voluntary families with children aged 0–3 years may self-refer to the program or be referred from other community agencies, such as the Saskatchewan Health Authority40. The KidsFirst program uses a strength-based approach to work with Indigenous families living off-reserve and non-Indigenous families to enhance parenting knowledge, provide support, and build on family strengths39,40. The program aims to assist families and foster healthy children through pre/postnatal support, home visiting, early child learning, healthy growth and development, and mental health and addiction services39. The KidsFirst North staff team across the 11 sites is composed of 35 professionals and paraprofessionals41, with six people forming the administration team and 29 forming the team of frontline workers. Administrator roles include a program manager, community development manager, accountant, program facilitator, and multiple supervisors. Frontline workers include home visitors, family wellness counsellors, prenatal outreach workers, coordinators, community wellness leaders, and screening and assessment workers42.

Our study was completed in collaboration with KidsFirst North including study design, data analysis, findings, and the relationship of findings within current research. To better meet the needs of the program and inform their quality improvement initiatives, a program evaluation using qualitative methods was completed. For the evaluation, the KidsFirst North team requested expansion of the initial focus on frontline workers to include families and administrators. Through discussions with KidsFirst North, our resulting study objectives were to (1) explore families’, frontline workers’, and administrators’ perceptions of factors that contribute to the successes and barriers of a maternal–child community health program for Indigenous families; and (2) describe the current role of frontline workers within health program planning, implementation, and evaluation.

Methods

Study design

As requested by the research partner, we followed KidsFirst North philosophies, approaches, decision-making processes, and methods of interacting with both staff and families41. Aligned with these philosophies41, we applied a community-based participatory research strength-based approach throughout the research process to facilitate a collaborative program evaluation and enable the work with KidsFirst North43. In addition, to help foster relational accountability between the researchers and KidsFirst North, the foundation of the project was created following Indigenous principles and values that include relationality, decolonization, and holism underpinned by the values of respect, relevancy, reciprocity, and responsibility44-47.

Researcher engagement

Engagement activities of the researchers included multiple trips to the KidsFirst North site in La Ronge; CT’s participation in the annual staff meeting (18–19 September 2019, Waskesiu, Saskatchewan); and ongoing connection with the KidsFirst North team in-person, by phone, and on a virtual meeting platform to build the research relationship and develop the study. Round table in-person and virtual meetings with the researchers, KidsFirst North leadership, staff, and families contributed to the study design including the research objectives, data collection procedures, data collection, and data analysis. For example, families exemplified the process of having a craft to work on in group discussions as a means of relationship building between participants and the group facilitators. To align with the families’ preferences and KidsFirst North practices, a picture frame craft was incorporated into the focus groups for data collection.

Sampling

Purposive sampling was applied to choose participants from the groups of interest who could provide the best information to inform the program48,49:

- For family participants, funding, distance, and time constraints limited the ability to access families at all 11 KidsFirst North locations. Through discussions with the program manager, the La Ronge office was determined as the location for the family portion of the project. Of the KidsFirst North sites, La Ronge provided access to a greater number of potential research participants. At the time of data collection, 10–15 families were accessing home visiting services and 6–11 families accessing the weekly group programs in La Ronge (J. Chartier, pers. comm., 19 February 2020; B. Graham, pers. comm., 5 March 2020).

- The KidsFirst North administrative team determined the annual staff meeting in September to be the best opportunity to engage with potential frontline workers and administrator participants. The annual staff meeting brings together all staff and administrators from the 11 program sites. Having all staff and administrators in one site provided access to the greatest number of potential participants.

Data collection methods

The time the researchers spent with KidsFirst North leadership, staff, and families provided opportunities for discussion to determine how the partners would proceed in the study and observational information of typical program practices to inform the study. Working collaboratively with KidsFirst North, we determined data would be collected using a demographic form, focus groups and semi-structured interviews. The qualitative approaches, focus groups, and semi-structured interviews mirrored the round-table, conversation-style discussions that were applied in family–staff–administrator and staff–administrator interactions. In addition, KidsFirst North had previous experience with these methods through a completed 2009 provincial evaluation of the program50,51. Although focus groups and semi-structured interviews are western data collection methods, these methods facilitate participants’ power and control over the information that is shared. Given that many of our participants self-identified as Indigenous, participants having power and control over the information that is shared is an important consideration to decolonizing research45,52. Refreshments, child care (for family participants), and an honorarium of a CA$20 (approximately A$22) grocery store gift card were provided to each participant as a thankyou for their time and knowledge sharing. This approach to gratitude was identified by KidsFirst North as highly valued by the participants.

Through the research development process, it was prioritized by KidsFirst North and the researchers that the collaborative, strength-based approach needed to extend to the data analysis process. The Collective Consensual Data Analytic Procedure (CCDAP) developed by Bartlett et al met our need53. In the CCDAP, participants are engaged at the onset of the analysis process. Participants work with raw data to develop clusters and name clusters into thematic results53-57. The CCDAP fosters a more relevant product for the research partner as it generates findings from the participant perspectives53-57.

The CCDAP allows the creation of spaces for Indigenous Peoples to lead the analysis and include their worldviews in research findings53. The CCDAP was developed as a decolonizing data analysis process to produce culturally relevant and useful information to apply in practice and positively impact health outcomes53. With many Indigenous families and staff in the KidsFirst North program, the decolonizing nature of the CCDAP was an important aspect in determining an analysis method that fit the context of our research project.

Recruitment and data collection

Participants were divided into two groups for recruitment, data collection, and analysis: KidsFirst North Families (n=9) and KidsFirst North frontline workers and administrators (n=25). From the 30 participants that completed demographic forms, 23 self-identified as Indigenous. Recruitment for each participant group was as follows.

KidsFirst North Families

The program manager requested that KidsFirst North staff such as home visitors, coordinators, and supervisors engage potential participants through verbal invitations to participate in January 2020. Following discussions with the program manager, focus groups were held to recruit samples of Indigenous KidsFirst North families (group 1) and KidsFirst North families from any ethnicity (group 2) (Supplementary figure S1). Group 1 inclusion criteria for focus groups and interviews were (1) being Indigenous, (2) previous participation in the KidsFirst North Program, (3) identifying as female, and (4) having one or more children. Group 2 inclusion criteria for focus groups and interviews were (1) any ethnicity, (2) previous participation in the KidsFirst North Program, (3) identifying as female, and (4) having one or more children. CT completed data collection and demographic forms at the KidsFirst North office in La Ronge on 29 and 30 January 2020.

KidsFirst North frontline workers and administrators

Participants were recruited by CT through verbal invitation, and data were collected at the annual KidsFirst North staff meeting in September 2019. Inclusion criteria for focus groups and interviews were (1) any age, (2) any number of years of work experience, (3) any gender, (4) any education level, and (5) any ethnicity. Participants were assigned to a focus group session by the program manager (Supplementary figure S2). The criterion for dividing staff into focus groups was based on their employment position within KidsFirst North (eg supervisors, home visitors, coordinators, and administrators). Grouping staff by this criterion removed the administrators from the group discussions, gave staff the freedom to speak, and reduced the power dynamic to create a safe space for sharing.

Data analysis

Audio-recorded data from the focus groups and semi-structured interviews were combined and transcribed for collaborative analysis. Following previous frameworks of the CCDAP53,58,59, we conducted data analysis in a two-part process. First, transcripts of the focus groups and interviews were printed in a 20-point font and passages that illustrated the participant contributions to the research questions were cut out and pasted onto cardstock. Passages that had identifying features, information not related to the research questions (eg discussion surrounding the community unrelated to the program, and confirmatory responses in agreement with the contributions of participants) were not included in the analyses. Second, a variety of 8.5 × 11 header cards were placed on a wall and a symbol (eg triangle, star, circle) was assigned on each header card. To avoid preconceived themes, the symbols had no prior meaning in the study. Cards with the passages were placed on a table randomly. Each passage card was read and placed under a symbol card according to the group’s direction. After 10–15 cards, individual participants chose a card and placed it on the wall under the symbol to which they thought it ‘belonged’. Participants continued this process until all cards were placed on the wall. Once the cards were placed in clusters, they were reviewed by the group. Any conflicting placements were discussed, and any requested changes were made to the clusters. Once the group agreed, the participants decided on the name or phrase for each symbol card (ie theme) that would communicate the meaning of that cluster. The data analysis conducted for each participant group was as follows:

- KidsFirst North Families: Data analysis was facilitated by the first author (CT) in one in-person session on 5 March 2020 at the KidsFirst North office in La Ronge (Fig1). Five families participated in the data analysis session. At the completion of the session, families reviewed the generated themes and supporting quotations. No changes were requested, and the themes and supporting quotations are reported as established by the family participants. Although another in-person community event was planned to share the family findings to a wider audience and obtain additional feedback, the COVID-19 shutdown in March 2020 prevented any future events.

- KidsFirst North frontline workers and administrators: Data from KidsFirst North frontline workers and administrators were analyzed in one in-person session for frontline workers and administrators on 25 November 2019, at the KidsFirst North office in La Ronge (Fig2). Participant groups were separated into two rooms; the first author (CT) facilitated the frontline workers’ group and the second author (AB) facilitated the administrators’ group. Virtual data analysis sessions facilitated by the first author (CT) were offered in February and March 2020 to each KidsFirst North site. For those participants unable to attend in person, analysis sessions were held online via WebEx. Through WebEx, participants reviewed PowerPoint presentations with the preliminary thematic results and supporting quotations, and had the opportunity to request any changes to the themes or placement of quotations. Consistent with the initial analysis session, groups were stratified into frontline workers and administrators. Themes were changed based on online feedback from participants (eg a theme change from ‘Policy barriers’ to ‘Policies in need of strengthening’ to be more ‘strength-based’). Once all requested changes were completed, an updated PowerPoint presentation was distributed electronically to all KidsFirst North sites for final review. No changes to the research results were requested and findings are presented as specified by the frontline worker and administrator participants.

After the analysis sessions were complete, themes were generated by each participant group, KidsFirst North Families, KidsFirst North frontline workers, and KidsFirst North administrators. Thematic findings for the factors of program success and program barriers were summarized for each group and are represented in in Supplementary figure S3, figure S4 and figure S5. These figures were explicitly chosen by participants as each theme was viewed with equal importance, and the findings are displayed in figures as circles of the same size in no order.

Figure 1: Collective consensual data analytic procedure (CCDAP) with KidsFirst North Families. This photo illustrates the clusters generated with KidsFirst North families in the CCDAP process on 5 March 2020 in La Ronge, Saskatchewan.

Figure 1: Collective consensual data analytic procedure (CCDAP) with KidsFirst North Families. This photo illustrates the clusters generated with KidsFirst North families in the CCDAP process on 5 March 2020 in La Ronge, Saskatchewan.

Figure 2: Collective consensual data analytic procedure (CCDAP) with KidsFirst North frontline workers. KidsFirst North frontline workers and researcher Charlene Thompson are shown completing the CCDAP process on 25 January 2019 in La Ronge, Saskatchewan.

Figure 2: Collective consensual data analytic procedure (CCDAP) with KidsFirst North frontline workers. KidsFirst North frontline workers and researcher Charlene Thompson are shown completing the CCDAP process on 25 January 2019 in La Ronge, Saskatchewan.

Ethics approval

This study was granted ethics approval by the University of Saskatchewan Research Ethics Board (Beh#18-165). Participants provided written or verbal informed consent. All data were de-identified and pseudonyms have been used to communicate results.

Results

Nine individual family participants were part of our study. Demographic forms were completed (n=9) and focus group discussions lasted between 17 and 47 minutes (Supplementary figure S1). Two participants were unable to attend a focus group and took part in an in-person semi-structured interview lasting 25 minutes. Data analysis was facilitated with five participants. Eight participants self-identified with Indigenous ancestry and had an age range of 20–44 years (Table 1). The individual family participants had a wide variety of educational backgrounds. Their length of involvement in the program ranged from 6 months to 15 years (Table 1).

Eighteen frontline workers and seven administrators participated in our study. Focus group discussions lasted between 41 and 56 minutes and semi-structured interviews between 23 and 27 minutes (Supplementary figure S2). Data analysis was facilitated with 10 frontline workers and 5 administrators.

Fifteen of 21 frontline workers and administrators self-identified with Indigenous ancestry. All were females aged 20–62 years (Table 2). Twenty of the frontline workers and administrators were full-time employees and had worked in the program from 1 month to 17 years (Table 2). Fourteen of the frontline workers and administrators were prepared with a certificate or diploma in early childhood education. Fourteen frontline workers reported a role in program planning and delivery, with approximately half reporting a role in program evaluation (Table 3).

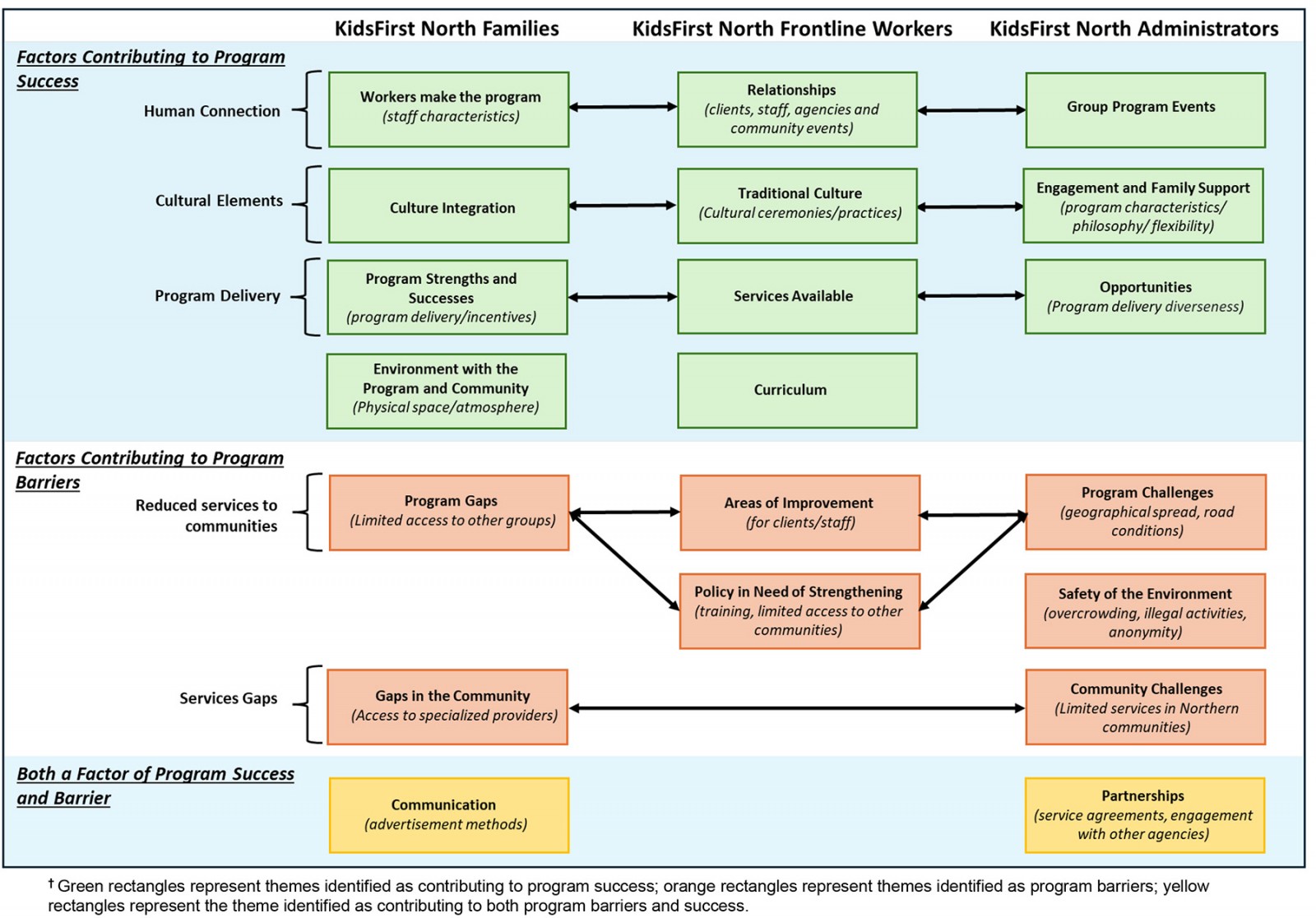

The thematic results from the KidsFirst North families identified four themes that impacted program success, two that created barriers for the program and one that occupied a dual role with elements contributing to program success and areas for improvement. Frontline workers identified four themes that contributed to program success and two that created program barriers. The administrator group identified three themes that impacted the success of the program, three that encompassed program challenges, and one occupied a dual role, impacting the program's success and creating some program challenges. The thematic results presented below are organized as factors contributing to (1) program success, (2) program barriers and (3) both program success and barriers. Group-specific themes are shown in Figure 3 and Supplementary figure S3, figure S4 and figure S5. Additional supporting quotations for the themes can be found in Supplementary table S1, Supplementary table S2 and Supplementary table S3.

Table 1: Demographic characteristics of participants in KidsFirst North Family participants’ group

| Variable |

Family participant responses (n=9) n (%)/mean±SD |

|

|---|---|---|

| Ethnicity | ||

| Self-identified with Indigenous ancestry | 8 (89) | |

| Did not respond | 1 (11) | |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 9 (100) | |

| Education level | ||

| Less than high school | 1 (11) | |

| High school diploma | 3 (33) | |

| University | 1 (11) | |

| Certificate or diploma | 1 (11) | |

| Undergraduate degree | 2 (22) | |

| Graduate degree | 1 (11) | |

| How did you hear about the program? | ||

| Care provider | 2 (22) | |

| Friend | 5 (56) | |

| 1 (11) | ||

| Workplace | 1 (11) | |

| Age (years) | 28.6±7.95 | |

| Length of time in program (years) | 3.4±4.63 | |

| Number of children | 2.3±1.41 | |

SD, standard deviation

Table 2: Demographic characteristics of participants in KidsFirst North frontline workers’ and administrators’ groups

| Variable (as per demographic form) |

Frontline workers and administrators (n=21) n (%)/mean±SD |

|

|---|---|---|

| Ethnicity | ||

| Self-identified with Indigenous ancestry | 15 (71) | |

| Caucasian | 4 (19) | |

| Did not respond | 2 (10) | |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 21 (100) | |

| Education level | ||

| High school diploma | 2 (10) | |

| Certificate or diploma | 14 (67) | |

| Undergraduate degree | 2 (10) | |

| Graduate degree | 1 (5) | |

| Did not respond | 2 (10) | |

| Employment type | ||

| Full-time employee | 20 (95) | |

| Did not respond | 1 (5) | |

| Previous work experience in maternal–child health programs | ||

| Yes | 5 (24) | |

| Administrators – previous work as a frontline worker | ||

| Yes | 3 (14) | |

| Age (years) | 44.4±10.52 | |

| Length of time in program (years) | 7.76±6.02 | |

SD, standard deviation

Table 3: Frontline workers and administrators – roles in maternal–child health programs (n=21)†

| Program area (as per demographic form) |

Current role as frontline worker (n=15) (n) |

Previous role in maternal–child health programs (n=21) (n) |

Administrators – previous role as frontline worker (n=3) (n) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Planning | 14 | 5 | 2 |

| Delivery | 14 | 5 | 3 |

| Evaluation | 8 | 4 | 2 |

† Some respondents have been involved in more than one role.

Figure 3: Thematic results – KidsFirst North Families, frontline workers and administrators.†

Figure 3: Thematic results – KidsFirst North Families, frontline workers and administrators.†

Factors contributing to program success

1. Human connection

Our three participant groups identified the importance of establishment of relationships between participants and staff. A key element present in the development of these relationships was the opportunity to establish and deepen support systems such as community events.

Workers make the program

For participants in the families group, a large portion of the discussions with participants centred around two streams related to frontline workers: characteristics of staff and staff actions. There was a consensus among participants that staff were ‘friendly’, ‘welcoming’, and ‘kind’, creating a supportive atmosphere for program families.

One participant described the staff by saying:

I think the workers make the program. (Hailey)

Relationships

For participants in the frontline workers’ group, discussions around program success centred on relationships and their importance to the program. Multiple aspects of relationships were explored by the frontline workers that went beyond the staff and family dyad. Participants viewed relationships to encompass three subthemes: relationships between clients and staff, relationships with agencies, and community events.

Community events were viewed as contributing to program success by building relationships between KidsFirst North and the community, and building relationships between families that attend the events. Opening the events to the ‘whole community’ was a recent change in practice that was perceived as positive to the program. Participants saw community events as a way to bring families together and remove that ‘isolation piece’ and build support systems. Rochelle articulated this aspect:

Strength of the events is when all your clients get together. They have a group discussion of what they do with their children and how they can help each other. Even though on the street, they have issues, but they all try to help each other. (Rochelle)

Group program events

For participants in the administrators group, participants discussed how group events offer benefits to the program, such as additional ways to convey the Growing Great Kids curriculum and alternative program settings. Group events often include participants who may not be currently enrolled in the KidsFirst North program. The events provide opportunities to involve more of the community to see what the program is about and build relationships:

Because oftentimes the group events can be used as an engagement tool to get families more comfortable and they will buy into the home visiting more once they realize what it is. But the group events are the piece that pulls them in and establishes the comfort zone. (Lori)

2. Cultural elements in programs

All participant groups identified the integration of cultural elements into the program as key to foster program success. Moreover, the cultural diversity was highlighted as a positive component to the program.

Culture integration

For families, the discussion of culture among participants was centred on Indigenous culture and how the program encompassed Indigenous culture. Some participants discussed the cultural aspects that were included in the program. Examples of activities included ‘berry picking’ and ‘family outings’. One participant discussed a relatively new cultural element as positive to the program:

I think that I like the fact that they have made it more culturally diverse now. So that we are learning from both perspectives … western medicine and First Nations perspectives. And traditional practices. (Shaylynn)

Traditional culture

For frontline workers, in discussions around culture, there was an overwhelming consensus among the frontline workers that culture was distinct for each community. Participants felt so strongly about this aspect that they requested the following statement be emphasised (shown as underlined text):

Like the culture, the traditions, and it’s different in every single community. (Tyra)

Carrie described the openness of inclusion in cultural ceremonies and that participation in ceremonial practices was not limited to any one culture or ethnicity, but open to the entire community:

In the ceremonial worlds, we invite everyone in to join us. It doesn’t matter where you come from. We don’t ask you where you come from. That’s your business. And if you want to come in and learn the ceremonial world, you are more than welcome to come and join us. Because we are trying to become one. (Carrie)

Engagement and family support

For administrators, a combination of elements, such as program characteristics, the program’s philosophy, and the inclusion of cultural aspects, were identified and discussed by administrators as fostering program success. Culture was described as important to the program, and staff are encouraged to examine the specific needs of each location and tailor the program to the community. The flexibility of the program facilitates cultural inclusion in the program:

And too … the flexibility that is written into our program where we can approach things with the appropriate cultural lens as well … that we understand the diverse needs and can respond to them better than a more rigid program. (Emily)

3. Program delivery

All participant groups determined that the different program delivery techniques for educational activities and services such as group events, counselling and home visits are a key part of the program’s success.

Program strengths and successes

For family groups, program assets were discussed in the context of how the program was delivered and program incentives. Participants highly regarded how education was delivered within the program. Multiple participants discussed how educational activities were informal and conversational:

It’s not like a sit here and pay attention because you obviously have to deal with our children at the same time. So, it’s kind of a round circle kind of conversation about that topic so it’s relaxed, which I think is more comfortable and less intimidating. (Allyce)

Services available

For frontline workers, the program offers a wide variety of services and delivery options that frontline workers identified as assets to the program. The program's successful service aspects included home visiting, group events, parenting and prenatal programs, counselling, and referrals.

The support of administrators was also viewed as contributing to the available services and success of the program. One frontline worker described how the administrators have an understanding of the program and that translates to support for the frontline worker in daily service provision:

And even the administrators get the heart of the program and that’s a really cool thing. So, the people who do the books and do the stats and stuff. They really understand the heart of the program, even though their skillset is with the data, right? ... I think that they really believe in what we are doing. And I feel that all the time. (Brooke)

Opportunities

The participants identified multiple features that encompassed program space and a wide variety of program delivery techniques as part of the program’s success. Home visits and group events were viewed as program assets. Lisa described the benefits of the group events:

Plus, you get the families to interact with each other. The social support. And they can see it in the families that the families really enjoy getting together with other families. (Lisa)

4. Other themes

Other themes identified by the different group participants are as follows:

Environment with the program and community

For families, this theme captured the participants' views of the physical space and the atmosphere of the program. The physical space was identified as ‘comfortable’ and informal, creating a safe space. The described comfort went beyond the elements provided in the physical space to incorporate the program's inclusive atmosphere. Gabby described both these aspects:

It’s nice because it feels like you are coming over to someone’s house and are hanging out in the living room. It’s chill. I feel like this is such an inclusive space for people of all … like social status or whatever. And that’s what you want with a community program. (Gabby)

Curriculum

For frontline workers, there was a consensus among participants that the Growing Great Kids curriculum was highly regarded and a major program asset. The curriculum offers a wide range of topics from child development to effective communication and some structure, but also enables the frontline workers to incorporate enhancements. The curriculum was described by the frontline workers as ‘great’, ‘fantastic’, and viewed as a great resource and tool for working with families:

That’s your golden key – the curriculum. You are never stuck with what to say. And I always use the curriculum for the primary child. (Lucy)

Factors contributing to program barriers

1. Reduced services in communities

Participant groups described reduced access to program services depending on age, marital status, location and community of residence of clients. Single parents, fathers, and First Nations Peoples living on reserves are among the communities with minimal access to program services.

Program gaps

For KidsFirst North families, the major program barriers related to creating additions to the current program. Multiple participants identified groups of people that the program was not capturing, such as single parents, dads’ programming, and people who were struggling. All participants felt these were significant areas that needed to be addressed by the program or in partnership with other agencies. Shaylynn identified the gap in programming for single parents and fathers:

I think there’s just a gap with both parental support in single parenting and co-parenting … with KidsFirst North, I think that they should have some sort of collaboration with dads’ programming and just put it out there to the community. Just as much as they do with mothers’ programming. Because I don’t think that there is enough of that. Like if men were invited to more things like that and to make it OK and not the stigma that men aren’t allowed to be curious and to have that sort of support. (Shaylynn)

Areas for improvement

For KidsFirst North frontline workers, the discussions for program improvement fell into three subthemes of impact: improvements for clients, improvements for staff, and a dual area of improvements for both clients and staff. Directly related to staff, frontline workers were identified as having a ‘huge job to do’, with workload and pay contributing to frontline worker turnover. Age restrictions that limit families’ eligibility for the program and the demand for transportation negatively impact both the clients and the staff.

Aspects of the program that could be improved for clients focussed on program enhancements such as additional services. Multiple participants discussed that the program needed to focus on more ‘father involvement activities’. In the experience of frontline workers, this sentiment had been echoed directly by community members. One participant explained how in her community, dads were pointing out their exclusion, which was a catalyst for change in the program:

… the dad kept asking how come there is nothing for dads? You always have moms’ stuff. So, they got together and they decided to have things for dads. (Joyce)

Policy in need of strengthening

Another theme discussed by frontline workers was that areas identified in policy varied greatly. Training needs included education to deliver the programming and ongoing training in cultural awareness. Prevalent throughout the discussions and a consensus among the frontline workers was the jurisdictional challenge of being unable to work with families who live on First Nations reserves. Participants requested the following statement be emphasised (shown as underlined text) as this challenge was viewed as greatly hindering the work with families:

We have a policy and it’s jurisdictional and so that’s kind of tricky for us sometimes. We are not supposed to work with on-reserve clients. So, we have to work within our community and that’s sometimes really difficult. (Brooke)

Brooke continued to describe the jurisdictional challenge and how staff attempted to support families living on-reserve:

… sometimes when someone wants to be part of our program who is on a reserve and we have to say … we try to do what we can with some programming, but with the home visiting program we can’t. (Brooke)

Program challenges

Various program challenges, from the small number of staff to the geography of Northern Saskatchewan, were discussed within the group of administrators. The challenges associated with the program's geographical spread included the travel required by staff, poor road conditions, and multiple program locations. The distance between sites creates a wide spread of staff and no on-site supervisor support. Emily summarized these elements:

And just because of the geographical distance that we have … that’s a huge challenge for the north … that we are one program located in 11 communities … we are pretty much half of the north. So, the travelling makes it a challenge, especially for the administration group of management and supervisors. The home visitors… may not have a supervisor in their community. (Emily)

2. Services gaps

Both the KidsFirst North families and the KidsFirst North administrators identified a lack of services for the communities, which results in negative experiences for both the staff and the clients.

Gaps in the community

Participants in the KidsFirst North families groups relayed additional gaps in service or care that were not the responsibility of KidsFirst North, but that impacted them as families in the program. For example, Christen described the challenge of accessing a lactation consultant:

I spoke to so many lactation consultants down south, but I never had any up here. (Christen)

Community challenges

Administrators identified that lack of services in northern communities and the resulting negative consequences experienced by the KidsFirst North staff create challenges. As a result, staff may take on additional workloads, roles, and duties they may be unprepared for in an attempt to fill these service gaps. Lori illustrated this point:

And the lack of other agencies and the added pressure on our program and on our frontline staff because in the absence of any other supportive services, ‘Tag we are it!’ And our home visitors would be drawn in to do more than what they might necessarily be equipped and trained for. But that’s because there is no other agency in town. (Lori)

3. Other themes

Other themes identified by the different group participants are as follows:

Safety of the environment

Participants of the administrators’ group also discussed safety as a program challenge in two contexts, home visiting and small northern communities. Multiple factors were identified as impacting home visitors' safety such as partners not wanting caregivers in the program, overcrowded housing, and illegal activities. Administrators also described how families and staff might know each other in the community. The small number of staff at each program location may not permit alternative assignments to eliminate any potential conflicts of interest between staff and families:

Yes, because in the north you deal with a lot of conflict because everyone knows each other and their families. Lots of them don’t have the extra person to assign them to. (Janet)

Factors contributing to both program success and barriers

Communication

Families discussed communication as having a dual role, a successful method and an area for improvement. Facebook was identified by multiple participants as an effective method used by the program to advertise and communicate program activities. Others saw areas where advertisement could be improved and more tailored to the northern communities. Clarissa discussed advertising with photographs of the program families and northern communities to motivate new families to come to the program. She described:

Posters too. Like changing a poster every year or half year. Just like to the Northern pictures of them [KidsFirst North families]. Like something to motivate them to come. Just like ‘I want my picture on there because it looks like you achieved a lot’. (Clarissa)

Partnerships

Administrators stated that partnerships can create challenges as well as contribute to the program’s success. Service agreements were viewed as a barrier in partnerships and described as having different ‘policies’, ‘terms and conditions’, and ‘holidays’, creating a disconnect between KidsFirst North and the contract agency. Thus, creating challenges to program delivery and negatively impacting frontline workers who feel ‘pulled in multiple directions’. Multiple participants described how partnerships provide an opportunity for staff to engage with other agencies and collaborate for group events. Emily explained that for staff:

… a lot of their work is done with other agencies in the community and in partnership with other agencies. (Emily)

Discussion

Our findings identified factors of program success and barriers from the perspectives of KidsFirst North families, frontline workers and administrators from rural communities in Northern Saskatchewan, Canada. Many factors of success and barriers of the KidsFirst North program overlapped among families, frontline workers, and administrators, illustrating agreement among these groups. There were some factors of program success and barriers that differed between KidsFirst North families, frontline workers, and administrators (Fig3).

Concordant with our study, staff are essential to the success of maternal–child health programs20,21,60, and staff characteristics (such as being warm, friendly, and welcoming) influence the families’ positive view of frontline workers31,61. Most studies that included family, frontline worker, and administrator participants aggregated data, limiting group-specific findings60,62. There were few studies like ours that discussed the importance of staff from the family perspective31,61. One such example is the Family Home Visiting Program evaluation in South Australia where family participants highly valued the staff characteristics that included being flexible and having personal qualities like being warm and friendly, and identified these as important in the relationship-building process61. Families were found to value staff’s characteristics to increase the comfort level, enable partnerships to work on parenting or other presenting issues, ie mental health, and foster families' continued participation in the program16,31,61.

Most of the KidsFirst North staff are local, Indigenous community members. No negative experiences with non-Indigenous staff were discussed by KidsFirst North families. However, the employment of local Indigenous staff is important to Indigenous families participating in health programs and linked to program success20,34,63. Local Indigenous staff have community cultural knowledge and may speak the language, which can build a culturally safe relationship between families and frontline workers20,21,34,63. The Family Spirit Trial, a home visiting program in the Southwestern US to promote positive parenting and reduce health disparities illustrated the importance of local Indigenous workers63. Local Indigenous paraprofessionals were chosen to deliver the curriculum over other frontline workers, like registered nurses. The community paraprofessionals brought multiple benefits to the Family Spirit Trial that included knowledge of the local culture, speaking the language of families, and a better understanding of the community, and were more acceptable to community members63. Given the importance of both staff characteristics and local Indigenous community members61,64, our findings suggest that programs need to develop hiring policies that bring these strengths to programs. This includes engaging families in the hiring process as suggested by Lowell et al to identify candidates with characteristics valuable to the program64.

KidsFirst North frontline workers identified jurisdictional policy as a challenge. This is specifically in rural settings, where a policy prevents families who live on-reserve from accessing the home-visiting portion of the program. This challenge creates difficulty and an emotional impact on the staff, who must turn those families away. Typically, jurisdictional policy challenges are discussed in the context of the impact on Indigenous families and include intergovernmental disputes, program access, funding inequities, and higher morbidity and mortality rates4,65-68. This is exemplified in a current program evaluation of the Aboriginal Head Start in Urban and Northern Communities Program, where a need for more flexible funding agreements is needed between the federal funding agency, the Public Health Agency of Canada and Indigenous recipients to address the local needs of families67. We found limited literature illustrating the additional impact of jurisdictional policies outside of families and community members to include that of frontline workers69. Although the negative impact of jurisdictional barriers on Indigenous family health outcomes is essential to consider65, the larger impact of jurisdictional policy beyond families to effects on frontline workers and the program should also be considered69.

KidsFirst North frontline workers further discussed how the stressors on staff created by jurisdictional policies have negatively affected the program itself. In accordance with the Health Council of Canada (2011), our findings suggest that working within systemic barriers and unsuccessfully navigating jurisdictional challenges may promote further strain on frontline workers, leading to burnout and turnover69. Once the staff leave the program, families lose the built relationships and trust with workers20,68, which may result in families dropping out of the program20,29,68. As the challenge of jurisdictional barriers extends beyond a maternal–child health program to a larger policy level, programs may need to examine strategies at the local level to reduce the risk of frontline worker burnout and turnover.

Despite the recommendation of including frontline workers in community health programs in all phases of the process, from defining the problem to evaluation formation and participation, there appears to be a disconnect between recommendation and practice4,14,20,21,35. Moreover, this inclusion has been explicitly recommended in Indigenous maternal–child health program literature4,16,34. Interestingly, in the case of KidsFirst North, frontline workers demonstrated a role in problem identification, needs assessment, planning, and development that appears to be largely unique and not found in most of the reviewed maternal–child health programs29,70,71. Other workers focus on providing input in resource adaptation and program delivery strategies to be more culturally responsive29,30,69,70,72,73.

Resource adaptation was illustrated in a Northwest Territories, Canada study to develop knowledge translation tools to increase First Nations mothers' breastfeeding rates71. Semi-structured interviews of eight First Nations mothers of infants aged less than 1 year and one Elder were completed to determine the breastfeeding beliefs, practices, and education methods that would best fit the community. One nurse and an undefined number of community health representatives made up the group of frontline workers on the community advisory committee. The community advisory committee worked to establish the best approaches to use for knowledge translation, such as videos, graphic art, and storytelling71. In this example, frontline workers were not included in the semi-structured interviews to inform the breastfeeding education program's priorities and content. In addition, their contributions in decision-making appear to have been limited to the development of resources and delivery strategies. In contrast, KidsFirst North frontline workers apply family input, combined with their frontline worker knowledge, to develop community event ideas, program content, and organize all logistical elements, such as supplies, advertising, and transportation. Program strengths within our study identified by family participants, such as delivery strategies, program environment, and staff making the program, suggests that the inclusion of frontline workers in these aspects of the program has created positive impact on the experiences of families.

To facilitate frontline worker inclusion, we identified factors that may have contributed to participation in program planning and evaluation outside of program delivery. KidsFirst North frontline workers have been given time and administrative support to foster inclusiveness, strength, and empowerment, and enable their engagement in problem identification, needs assessment, decision-making, and planning and development34,74. Time and administrative support were illustrated in the Southcentral Foundation (SCF) Nutaqsiivik/Nurse-Family Partnership program34. The SCF program provides education and support to families of children up to the age of 2 years in rural and urban Alaska, US34. Like KidsFirst North, SCF frontline workers led the problem identification and needs-assessment activities to direct the program34. The SCF operates within an organizational philosophy that values relationships and centres this approach for interactions with families and among frontline workers and administrators. Similar to KidsFirst North, this philosophy and the time provided to SCF frontline workers appear to have facilitated the inclusion of staff in the problem identification, needs assessment, and development of the program34. Other programs may want to consider providing time and administrative support within the program planning and evaluation cycle to foster frontline worker inclusion. Inclusion of frontline workers in program planning and evaluation has been suggested in the literature to offer multiple benefits to the staff and program itself4,20, such as greater levels of engagement and investment in the program in staff, which may assist in employee retention20,66,75, as well as improved relevance to the community, increased participation, and overall success of the program4,16,64.

Culturally safe care can be defined as an outcome of receiving care where respectful engagement exists, power imbalances are addressed, and people feel safe76. Cultural safety can only be determined by those who are experiencing a service or program77. Some aspects of programs to foster cultural safety include participants having power and control to influence program practices and policy; responsiveness to participants’ needs; participants having relationships and trust with staff; and integrating Indigenous knowledges and practices in the program4,14,78. An example of these practices was found in the Aboriginal Infant Development Program in British Columbia, Canada, which offers home visiting, outreach and group programming to support family and children’s health33,60. Within the program, participants and staff highlighted the importance of engaging with caregivers to determine programming direction, families’ needs, and relationship building to the program’s success33,60. In our study, the KidsFirst North program serves both Indigenous and non-Indigenous families. However, our findings reflect family experiences and program practices that are recommended to foster culturally safe care for Indigenous families. All participant groups reported families identifying their own priorities to direct the program initiatives, illustrating power with family participants. The importance of relationships and trust was exhibited in the positive relationships with staff reported by families and value of relationships within the KidsFirst North program philosophy and practices. In addition, the intentional inclusion of Indigenous practices such as traditional parenting demonstrates the program’s initiatives to foster cultural safety. The findings from our study illustrate very tangible practices that other programs may consider to foster culturally safe care for families.

Our study has some important strengths. We used CCDAP to collect and analyze KidsFirst North families' perspectives, frontline workers, and administrators separately, which allowed us to access the unique voices and specific nuances of these different groups. This allowed us to identify themes that might not be evident in grouped findings of other studies. Although our findings may not apply to all Indigenous families accessing programs79,80, there are elements that may be relevant to other programs. Additionally, to ensure a collaborative approach with our research partner in knowledge translation, this manuscript was shared with KidsFirst North for feedback and approval prior to submission for publication.

Some limitations should be considered. First, research participants were limited to current families and staff, and may not represent differing views from past families and staff. Second, families were recruited by staff at one program site, which may have led to a sample of participants who were actively engaged with the program and may have created some selection bias60,81. Third, due to the COVID-19 pandemic and subsequent shutdown in March 2020 the additional in-person community event for family feedback on the study’s results was cancelled for the foreseeable future. With no additional opportunities to seek additional family and community input, the results were limited to family feedback in the completed analysis.

Conclusion

Our project has brought a unique lens to maternal–child health program research by examining the specific perspectives of families, frontline workers, and administrators. The importance of staff and their crucial influence on the families’ experiences was key to program success. The negative impact on frontline workers of policy that prevents families living on-reserve from accessing the program was an unexpected finding that warrants staff support and future consideration. KidsFirst North frontline workers led problem identification and needs assessment, and made decisions in development and planning, roles in the health program planning and evaluation not found in most reviewed maternal–child health programs. This knowledge may be helpful to engage frontline workers outside of program delivery in broader aspects of program planning and evaluation. Contributing to the evidence base of maternal–child health programs that serve Indigenous families may help foster the success of public health programs and positively impact the health of Indigenous children and families.

Author information

CT is a non-Indigenous woman who lives and works on Treaty 6 Territory and the Homeland of the Métis. As Assistant Professor with the College of Nursing, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, her research has centred around public health, working with Indigenous mothers, children, and families to reduce the burden of health inequity. RC is a Métis woman who has lived and worked in Northern Saskatchewan her whole life. RC is the program manager for KidsFirst North and the Early Years Family Resource Centre. RC loves her jobs and the North, providing family-centred services to northern families and residents. AB is a white settler from Great Britain, Dr Bowen is committed to Truth and Reconciliation to First Nations, Métis and Inuit Peoples. Dr Bowen was a registered nurse and trained midwife and is now a professor emeritus. She has extensive clinical, educator, and administrator experience in maternal physical and mental health. Her research focus, into understanding the mental health of mothers and vulnerable women, led her to research into bringing back Indigenous birth practices in Canada and Australia. DR is a non-Indigenous professor emeritus and retired nurse professional from the University of Saskatchewan living on Treaty 6 Territory and the Homeland of the Métis. DR conducts population-based research with children and families in the community. For the past 10 years, DR has participated as a researcher with First Nations communities, primarily examining health-related challenges of children and their families. MS is a non-Indigenous gay man who lives and works on Treaty 6 Territory and Homeland of the Métis. MS is a Professor in the School of Public Health, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon. MS’s teaching, research, and outreach work all focus on using quantitative and qualitative methodologies to help address public health challenges facing marginalized populations. CT, AB, DR, and MS are authors and researchers committed to truth and reconciliation and collaborating with Indigenous community partners to co-create knowledge that can work towards closing the gaps in health outcomes between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Peoples.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the support and partnership of the KidsFirst North families, leadership, and staff who made this study possible. CT would like to acknowledge the editorial support from Alejandra Fonseca Cuevas, Research Assistant, College of Nursing, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, SK, Canada.

Funding

Funding for this research was provided by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) Doctoral Research Award – Priority Announcement: Aboriginal Research Methodologies CIHR 201610DAR-383834-283432.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare they have no conflicts of interest.

* ‘Indigenous Peoples’ identifies the First Peoples or those who inhabited countries such as Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and the US before colonization82. In the Canadian context, ‘Indigenous’ may include First Nations, Métis, and Inuit Peoples; however, in this article the term has been applied as recommended by Allan and Smylie82 to support the self-definition of individuals and communities and consider the diversity of Indigenous Peoples in Canada.